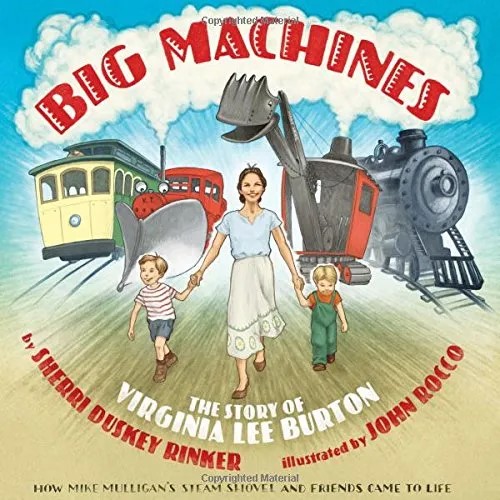

Big Machines: The Story of Virginia Lee Burton – written by Sherri Duskey Rinker, illustrated by John Rocco

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017

Explaining to children how creativity works is both challenging and rewarding. Presenting the process through which an author and illustrator of picture books produced some of their favorite characters is especially significant. In Big Machines: The Story of Virginia Lee Burton, readers learn how a multitalented artist with a consuming vision accomplished magic. Burton brought to life machines about to be made obsolete, houses threatened by urban expansion, and steam trains bored with jobs. (She even wrote and illustrated a comprehensive history of life on earth called Life Story.) Sherri Duskey Rinker and John Rocco have constructed an accessible path towards understanding Burton’s gifts, motivations, and lasting importance.

Although Rinker refers to Burton as “magical,” it is clear at the same time that she is down-to-earth. A mother, a dancer, a gardener, and a neighbor, Burton could be any member of her community, except that she is different. “With a few taps of a wand,” Jinnee, as she is known, “creates animals. She can also make the seasons change, and conjure heroes and people of all sorts.” There is a risk in emphasizing the almost mystical aspect of artistic creation, but both words and pictures depict how Burton’s wand is a paintbrush, and that her innate talent only allows her to conjure and create through hard work.

Burton appears at her desk from a bird’s eye view, meticulously drawing and erasing. Rocco does not attempt to reproduce her style, but rather to suggest it, perhaps even to conjure her artwork in a reflection of the way she herself created a world. The machines that she loved are the central focus of the book.

We see her, standing along the track with her son, drawing a life-sized steam train. Michael, her little boy, had inspired her work on Mike Mulligan. He observes his mother’s vision of Mary Anne come to life in all its functional detail. Katy the snowplow transforms a blank sheet of white paper into bright color, as Burton draws and paints the tough red Katy into a determined character. Burton and her children stand alongside the completed scene.

Readers may be reminded of Crocket Johnson’s Harold with his purple crayon, resolving dilemmas by drawing, but the meld of fantasy and reality in Burton’s biography has a somewhat different purpose. Standing inside the little house as she draws it, the artist is not saving herself from danger or finding a missing home. Instead, she is realizing an idea of art and engineering as complementary, with both approval of change and nostalgia for inevitable loss.

Burton’s sons are worried at the little house’s imminent displacement by “Roads! Buildings! Traffic!” and the inevitable darkened skies they bring. But a flatbed truck hauls the house to safety and the big city remains. Rinker and Rocco establish that Virginia Lee Burton’s life wasn’t one of either/or, but of both/and. Even as Mary Anne is rewarded for her hard work with a useful role in retirement, and Maybelle the cable car stubbornly keeps her route, Burton’s genius is the animating force behind these contrasting approaches to progress. The artist’s “wavy and curvy, swoopy and swervy” lines are still a constant presence in the world of children’s books.