Afikotective – written and illustrated by Amalia Hoffman

Kar-Ben Publishing, 2024

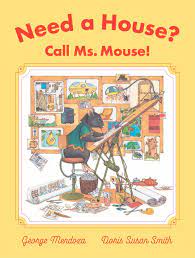

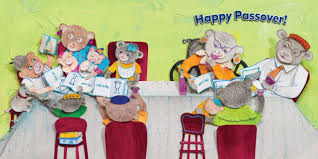

Every year there are new books about Passover/Pesach for children. Some have novel premises; others are contemporary versions of classics. Amalia Hoffman’s Afikotective features a family of mice ensconced in a cozy home. Mice have appeared in Passover books before (such as Matzah Belowstairs, Mouse in the Matzoh Factory, Pippa’s Passover Plate, or The Passover Mouse), so Hoffman’s are in good company. The concept of hiding is intrinsic to the Passover seder. Customs vary among different Jewish communities, but often the middle matzah of three is hidden by an adult, to be found by a child, who will receive a reward. Only then can the seder be completed. Hoffman’s mice are rendered in sophisticated images that allude to fabric art, and they embody the home-based ritual which is central to the festival.

In this family the grandparents hide the afikoman. The grandfather wears a large, Sephardic style kippah/yarmulke, and the grandmother sports cat-eye glasses and bold dangling earrings. The bright orange of their outfits match! One of the children at the table wears a bowtie and a deerstalker hat, signaling the detective role he will play.

He employs some obvious tools, like a magnifying glass and binoculars, but also a toy elephant with a super sensitive trunk. The logic of his search technique will make perfect sense to young children, even when he encounters a few detours and needs to get out his toolbox.

Amalia explained her creative process to me. She sketched and colored each picture, and then cut out the shapes and composed them on a board, painting them and scratching the surface to add texture. Curving parts of the mice gives an allusion of animation. Finally the images are photographed. (The afikotective sniffer-leash and the word “YAY” were produced with yarn.) Images are textured and layered to appear three-dimensional. The ingenuity and precision behind these heimish (homey) scenes is the result of loving attention to detail.

Children and mice are both small, but their stature does not minimize their important role in the celebration of Passover. In fact, adults are obligated to teach them the story of the Exodus, and for everyone to experience it as if he or she had actually been alive at the time. Young readers will undoubtedly feel affinity for the other species in this book. They can even make a copy of the “Afikotective” badge included. In her author’s note, Hoffman reveals the origin of this special identity in her own childhood.