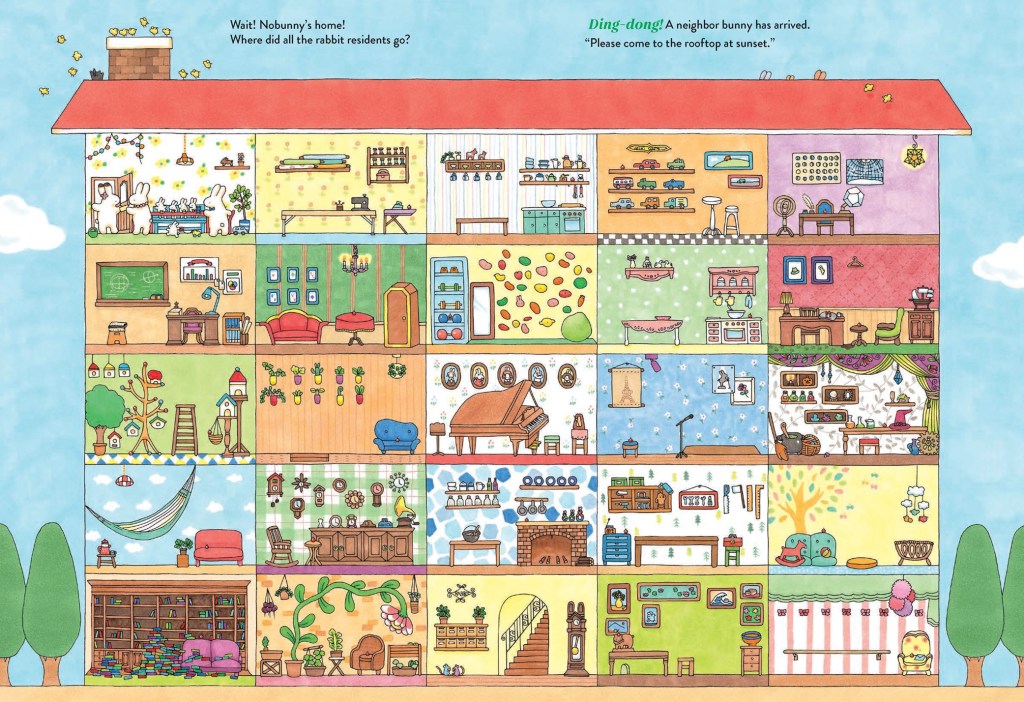

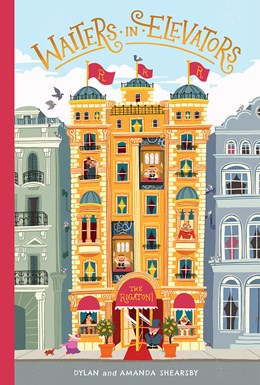

Welcome to the Rabbit Residence: A Seek-and-Find Story – written and illustrated by Haluka Nohana

Chronicle Books, 2026

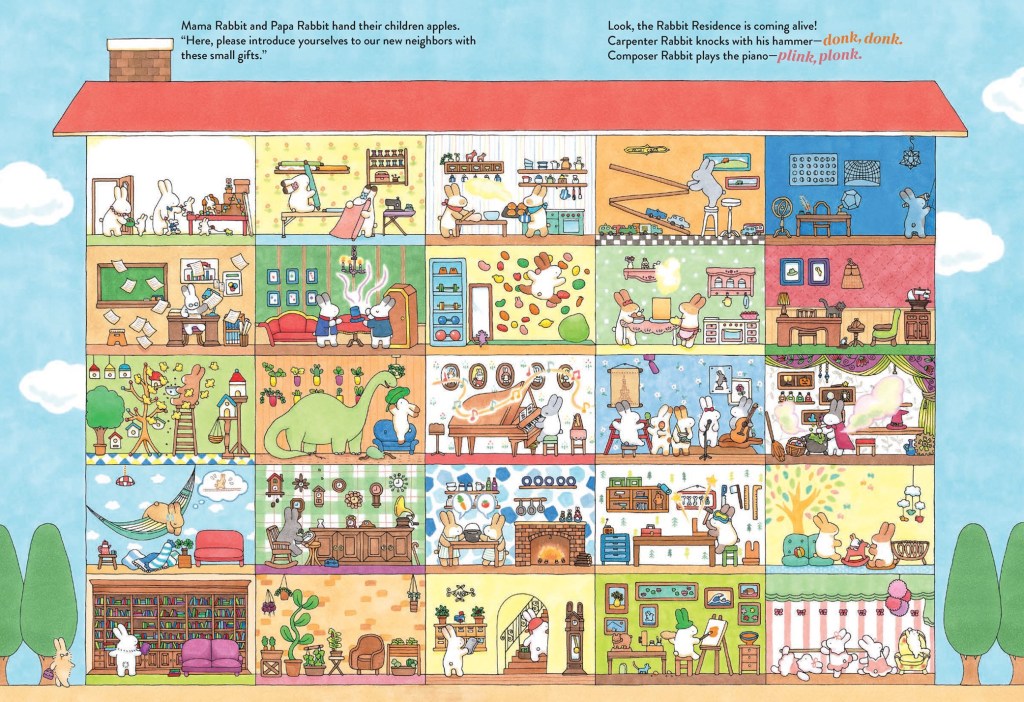

Following her earlier book about animals having fun while living in detailed habitats, author and artist Haluka Nohana has now invited readers to a rabbit residence full of activity. Even early in the morning, there’s a lot going on, even if not everyone is awake. Each room is a complete picture in itself, but the sum total of the cutaway house is a collective delight. The endpapers introduce the rabbits residing in the house. There are bakers, a wizard, a painter, a dinosaur keeper, a band, and many other essential professions. There are quintuplets, not so unusual for rabbits, a clockmaker for an old-fashioned touch, and a sleepy rabbit holding a blanket. He must be too young to have a job. There is a four-page fold-out spread with text and a full view of the house, and subsequent pictures describe the action, and the text suggests indirectly that reader might want to look for a particular rabbit pastime. “Composer Rabbit plays the piano. – plink, plonk.” Some of the onomatopoeia seems as if it might be taken directly from the original text in Japanese, which adds an intriguing note: “Meanwhile, Painter Rabbit is painting, peta, peta.” The sounds connected to rabbit tailoring are “choki, choki.”

It’s easy to make rabbits appear cute, but these are quite distinctive, even within that category. They are rounded and fluffy, a bit similar to Moomins. Lots of accessories, as well as brushstrokes denoting movement, add to their strangely realistic appeal. A rabbit exercising seems to have fallen and is seeing stars. A dinosaur with a long neck, maybe an apatosaurus, leans down into the room below to offer a plant to a clockmaker. There is some ambiguity in these scenes, including magic involving a genie rabbit, whose swirling body may or may not be related to the waft of fragrant steam emanating from the kitchen. A mildly dissonant picture shows an almost empty house, framed by the question, “Wait! Nobunny’s home! Where did all the rabbit residents go?” The rooms appear different without all the busy rabbits. Books are strewn about the library. A lone telescope has no astronomer, and the magician’s studio shows an empty hat and a cauldron at mid-stir. It turns out that this swanky building has a rooftop open for a party, with all the familiar tenants as well as the light of shooting stars.