The Three Little Mittens – written by Linda Bailey, illustrated by Natalia Shaloshvili

Tundra Books, 2023

The Three Little Mittens opens up several questions about being the odd one out. First, and most literally, “What’s the use of single mitten?” More generally, we’re asked to consider, “Why do you have to match?” Finally, can an assortment of mismatched items find a home together and even encourage others to do the same? Children’s picture books have always been a welcome location for exploring these issues, and for questioning rigid categories that separate people, animals, or other beings from one another. Humorous childlike thoughts and joyful pictures align the book with other classics, including Leo Lionni’s Little Blue and Little Yellow, Margaret and H.A. Rey’s Spotty, and both Antoinette and Gaston, by Kelly DiPucchio and Christian Robinson.

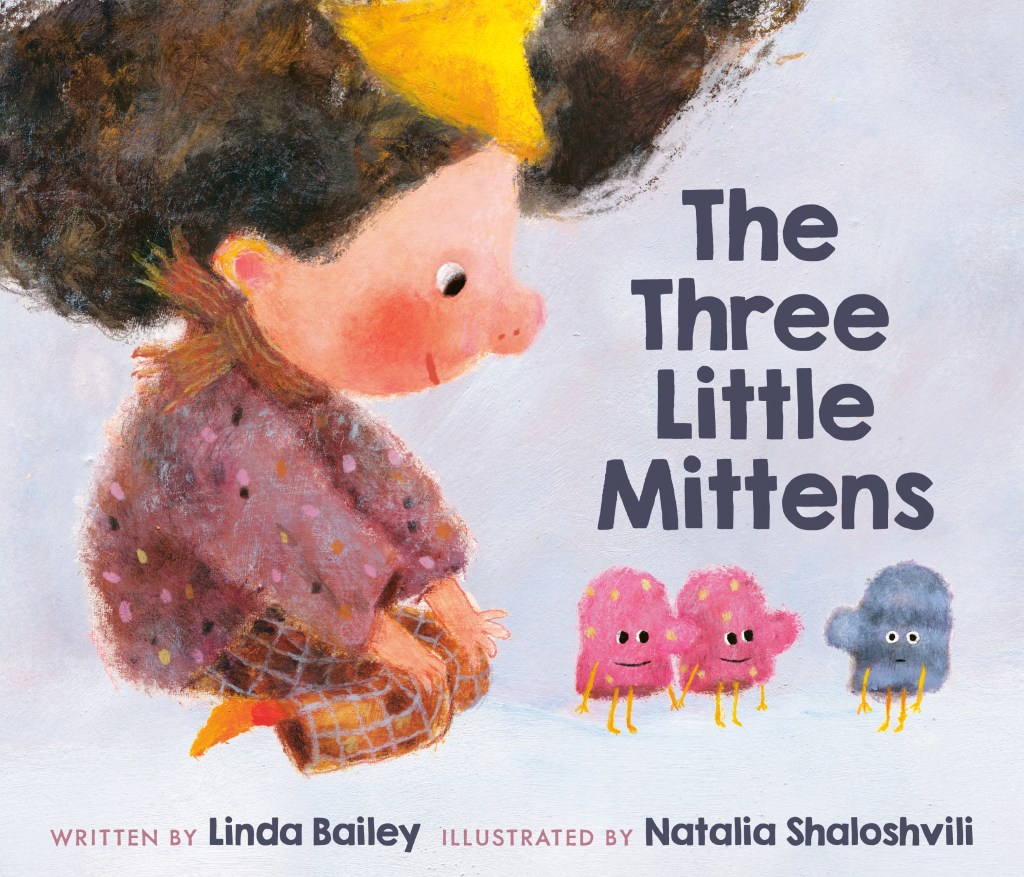

The connections are subtle. The mittens depicted here are not subject to the same type of prejudice. They judge each other, conforming to unreasonable outside standards of who has value. When Stripes gets detached from her partner, a common hazard for mittens, she suffers a kind of existential panic, but insisting “I know I’m just one…but there must be some reason why I’m here.” But instead of reassurance, she suffers rejection, as Dotty and Other Dotty hold hands and walk away from her. With just three squiggles per mitten, Natalia Shaloshvili captures the pink mittens haughtiness, and the bereft mood of one Stripes, matching Linda Bailey‘s playful text.

Just sticking with mittens would have made the story seem more of a parable. When a Little Girl appears, the mittens, and the reader, begin to experience other possibilities. Her features are formed of the same flexible line as those of the mittens, but she also has beautiful dark curls, a jaunty hat, and a playful dog. Most importantly, she in addition to her pink pair of mittens, a blue one peeks out of her pocket. Maybe there is hope for Stripes after all. When one mitten falls off the girl’s hand, a new relationship begins. It starts, from Dotty’s point of view, as a last resort, but soon the two single mittens tentatively form a partnership.

While Lionni’s green and yellow geometric forms effortlessly play together, Shaloshvili conveys a great deal of ambiguity in each simple picture. Their stick-like limbs swing in motion, and their bodies sometimes shed a bit of fuzz. The white space on each page is not only snow, but a spacious background for their drama. More characters appear when the Little Girl goes indoors and opens her cardboard box, full of highly individual mittens who are not abandoned, but given a new life. There are such unforgettably warm collectibles as Pom-Pom, Big Dino (only big compared to the other mittens), and the decorative Furry Cuffs. The Lost Mitten Box is, just by being placed in a container, a curated collection, but only minimally. The mittens all get to come out in play according to a fair system devised by the Little Girl: …over time, all of the mittens would get a turn.”

The finale is a range of possibilities, all representing “FREEDOM.” Children and mittens play together. Their lives are full of wonder. It was easy to resolve the questions about the potential uses of a single mitten, the necessity of matching, and the viability of existence.