A Song for August: The Inspiring Life of Playwright August Wilson – written by Sally Denmead, illustrated by Alleanna Harris

Levine Querido, 2024

For a reason that has never been clear to me, there are few picture books for children about theater and its creators. Scientists, authors, inventors, activists, are all the frequent subject of biographies for children. But acting, directing, and writing plays are rarely the focus of these works. Children are future theatergoers, and sometimes future writers for the stage. Sally Denmead and Alleanna Harris’s new book about August Wilson begins to correct this gap. Finally, the brilliant chronicler of Black life in America, author of the Century Cycle, is the focus of a book accessible to young readers.

Sally Denmead sets the scene with the book’s opening in 1940s Pittsburgh, where August was born into a working-class family. Obstacles to success are familiar territory in biographies; Denmead uses spare but dramatic descriptions to establish the improbable nature of Wilson’s future success. His father abandoned the family. His mother struggled to support them, imbuing a love of words in her son. Aleanna Harris depicts August’s face only from the eyes upward, as he seems to meditate on the beauty and power of language. Denmead stresses two aspects of language that intrigued him, the mechanical and the melodic: “August liked words. He liked taking them apart to see what they were made of. He liked the way words had their own kind of music.

Parental support can only go so far when the rest of the child’s world opposes him. Denmead describes the humiliation of a teacher who disbelieves that August could have written an outstanding essay. Other students isolate him, and bullies attack him. In an American tradition no less powerful for being common, August determines to educate himself in the public library. We see him ascending the steps of that grand building and immersing himself in its treasures. In one picture, Harris chooses to depict the books that enthrall August as a kind of metaphor. Instead of choosing actual authors, she designs stylized volumes without legible titles, as if the range of his interests were too great to contain.

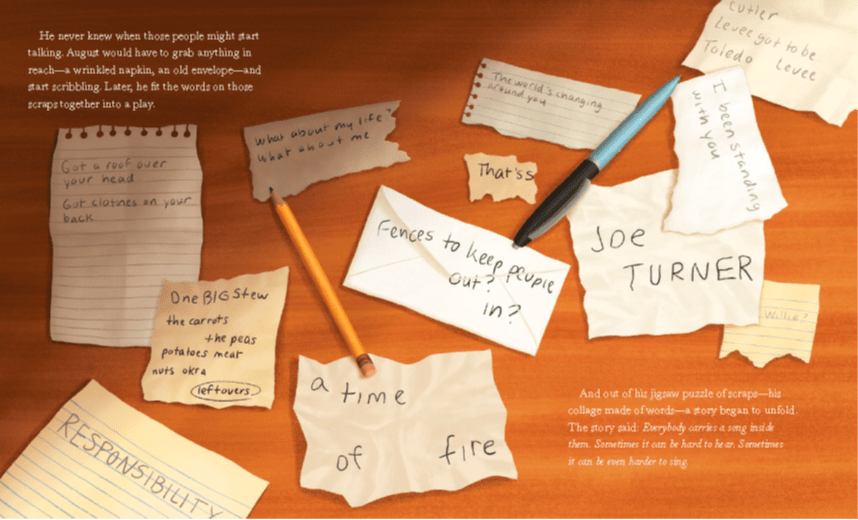

There is a challenge in writing for children about a playwright whose works might be most meaningful only when they are older. Denmead emphasizes the breadth of Wilson’s influences, the way that he combined history, visual art, and music in his compelling stories of Black life. His characters work, joke, holler, and sing, like the real people he has encountered in life or in books. Two pages show scraps of paper that document the playwright’s creative process. The statement that “He never knew when these people might start talking,” offers readers a glimpse into Wilson’s mind, echoing back to his earliest fascination with language. Denmead also repeats her allusion to music, as Wilson works hard to access the music he hears. Only then can he construct the characters who come to life in his plays.

A Song for August concludes with a list of plays accompanied by their Playbills, visually identifying the products of Wilson’s body of work. Denmead’s author’s note provides additional background.