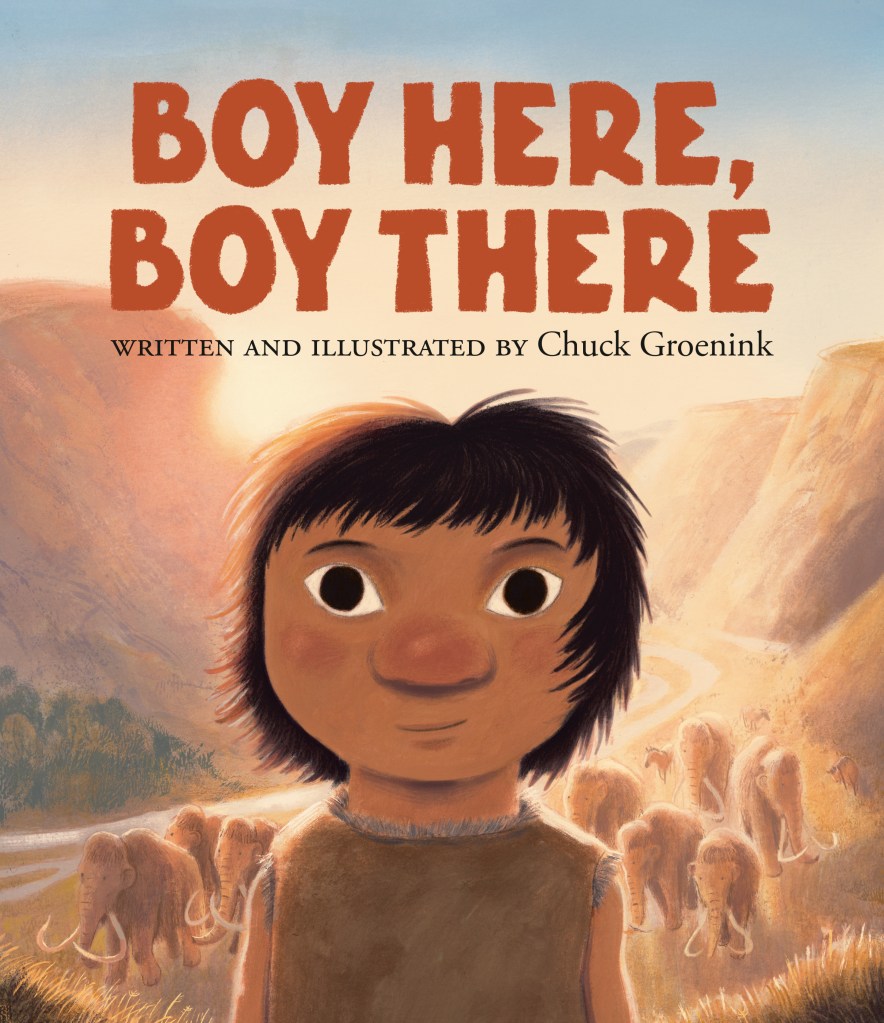

Boy Here, Boy There – written and illustrated by Chuck Groenink

Tundra Books, 2024

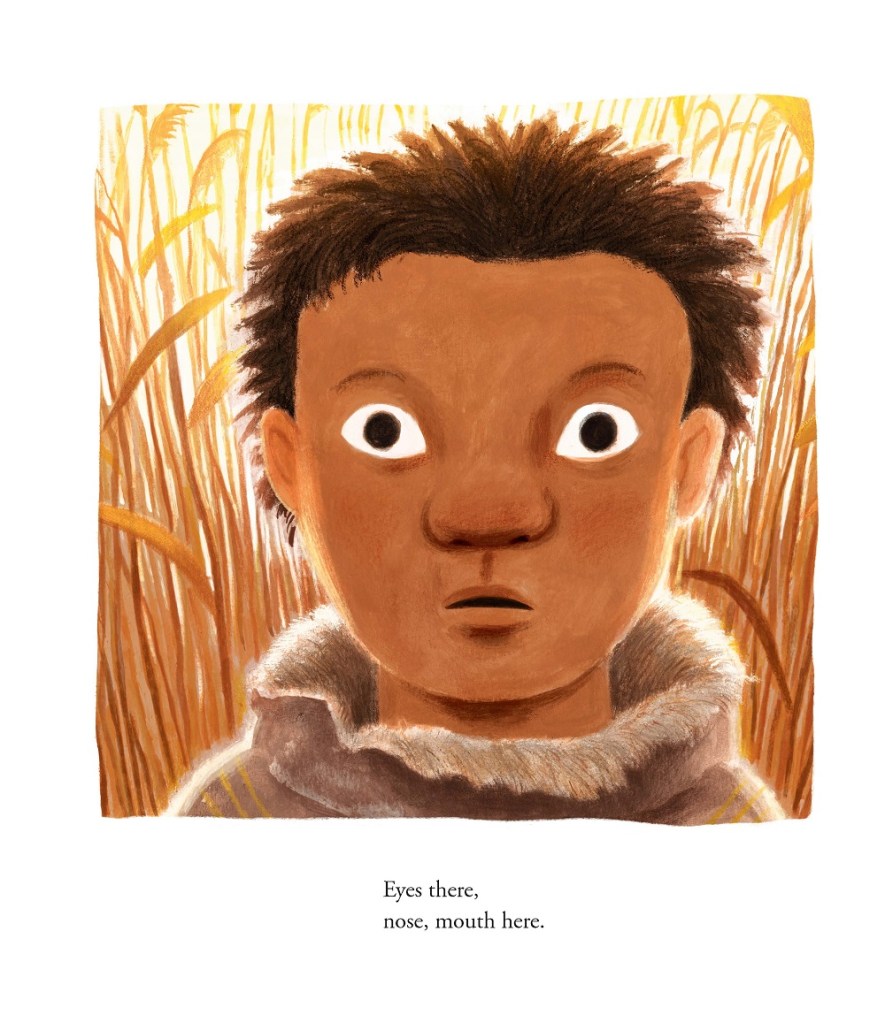

The premise of this wonderful new picture book is the chance encounter between a Neanderthal child and his Homo sapiens counterpart. Not only young readers, but many adults, may not realize that archaic humans and their counterpart overlapped in time from when the two groups diverged, between three and four hundred thousand years ago, and when the Neanderthals went extinct some 40,000 years ago. (The overlap in space, however, may have been brief; an author’s note carefully explains this part of evolutionary history.). Boy Here, Boy There is not a work of fantasy, but an imaginative exploration of early human society, undergirded by fact. The stunning pictures and poetic text recreate the plausible story of one curious boy as he interacts with the natural world, and eventually, with a kind of mirror image of himself.

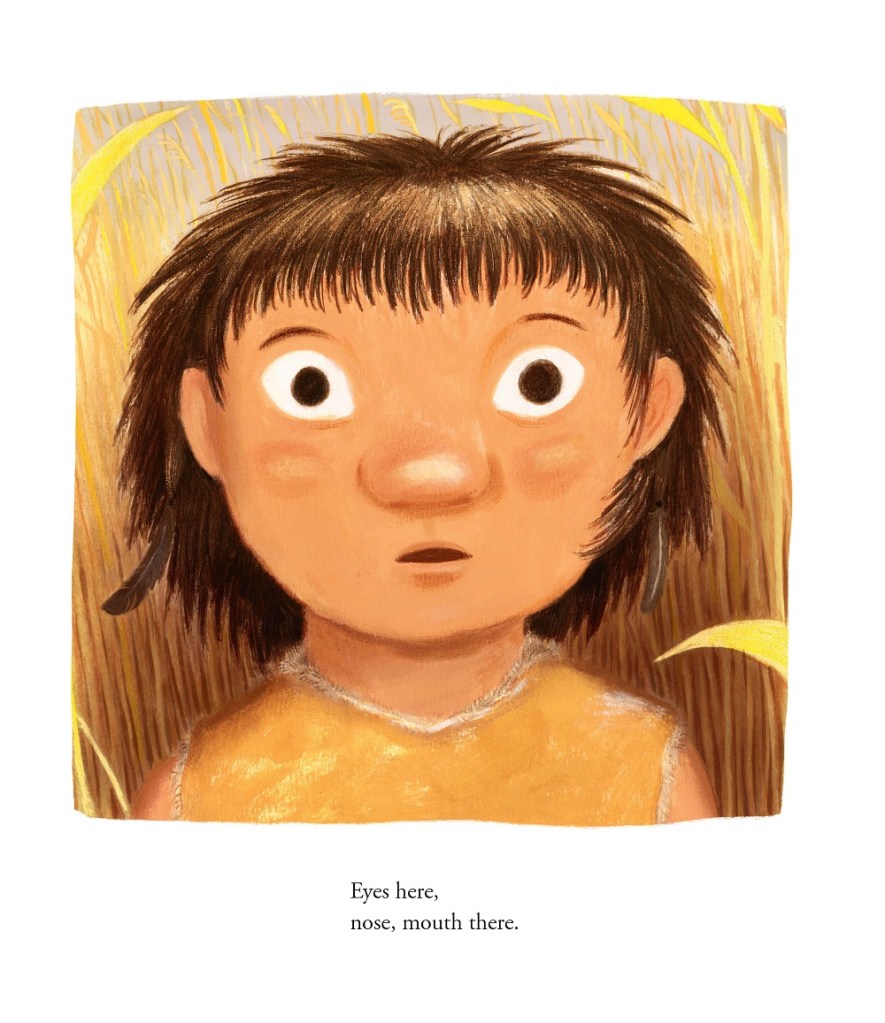

Presenting prehistory to children may take the form of nonfiction narrative, infographics, or historical fiction. Chuck Groenink instead builds character through accurate pictures rendered in soft earth colors, and in words that open a window into the boy’s consciousness (I previously reviewed a wonderful book he illustrated for another author). Popular depictions of prehistoric humankind are sometimes intentionally comic. Parallels to modern people may be noted ironically, patronizingly, or just as a type of ridicule. Groenink is well-aware of this model and purposefully avoids its temptations. We have limited information about Neanderthal speech, but anthropologists have offered insights about its level of complexity. On the other hand, children’s way of thinking and speaking is well-documented. As Wordsworth famously understood, “The Child is Father of the Man,” while scientist and philosopher Ernst Haeckel coined the memorable phrase, “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.” In other words, human development on the micro level parallels the development of the species. Groenink succeeds in distilling that truth in a remarkable way.

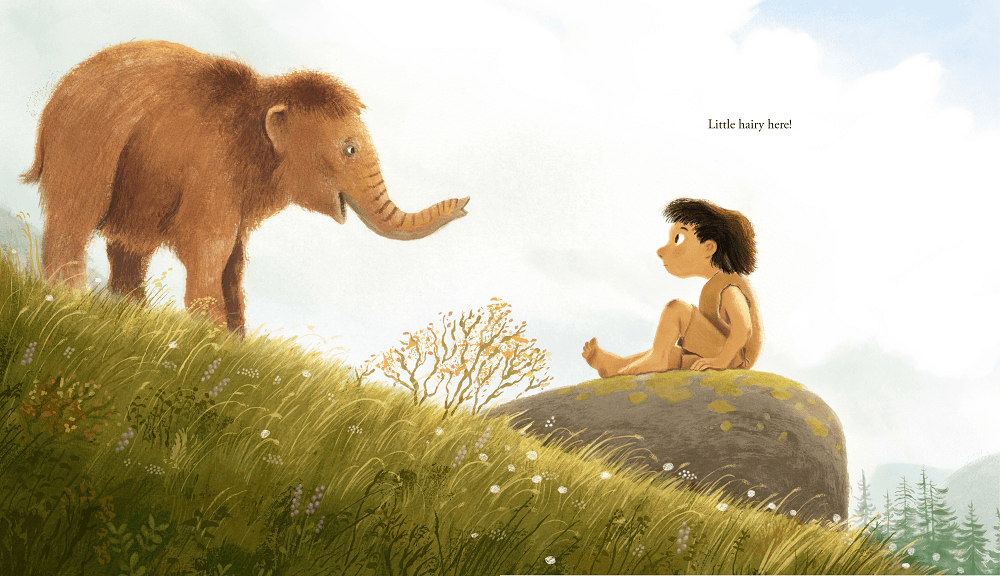

Whatever the Neanderthal boy observes in nature, he names descriptively. Owls, birds, rabbits, and deer are translated into “Runners, jumpers, fliers and pouncers everywhere.” The actual feathers of a bird and the soft grass on which he lies down are two variations on the same substance: “Feathers in sky. Feathers in hair.” The artistry that Groenink uses to capture a child’s thoughts, and the language of humankind in its childhood, elevates his book. Readers expecting a wooly mammoth will not be disappointed. The boy faces the cheerful looking animal, again finding a similarity between himself and the “Little hairy,” the child of the huge “big hairies” of the herd.

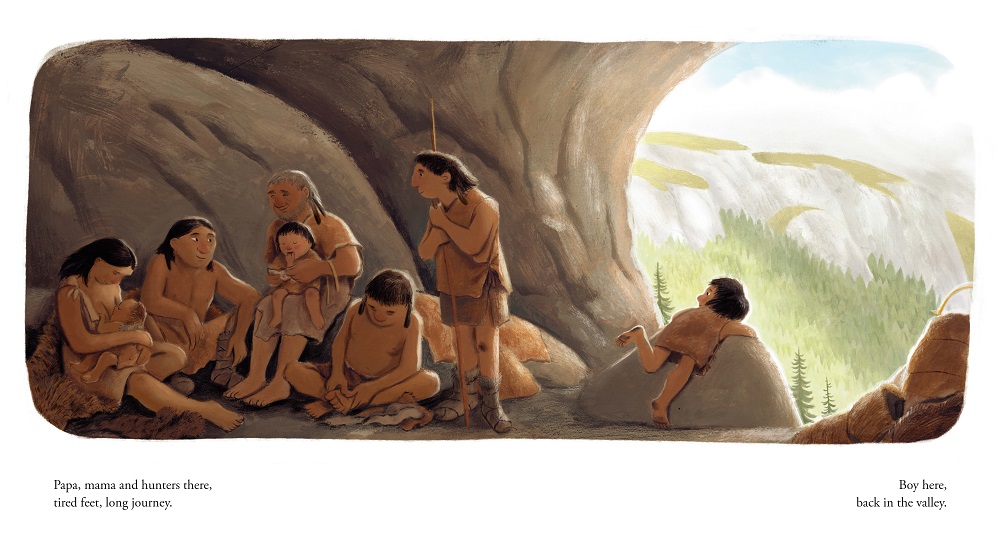

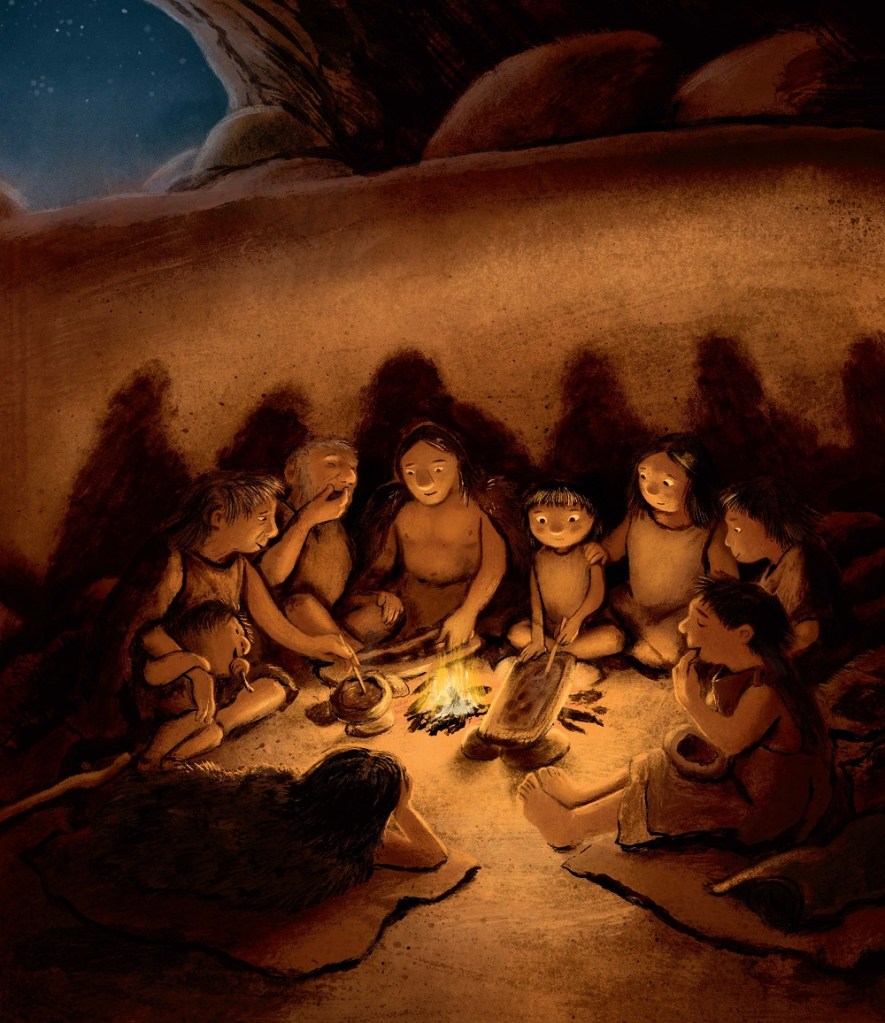

Neanderthals lived in communities where adults contributed to finding sustenance and caring for children. Their work is tiring, as the boy notes. The hunters sit for a brief rest, with one woman breastfeeding her baby. At night, they gather for a tender family scene in a cave dwelling. There are different generations represented; one older man appears to cover a yawn. A child reclines on a parent, and everyone watches food cooking on a fire with great interest. After his day exploring, the boy is content to be “Boy here, home again.” Without forcing an emotional connection to contemporary life, one just emerges from the pictures and text: “Fire there, food bubbling, a full belly, family together.” Neanderthals created works of art. There are none of the familiar cave paintings here, but the boy makes a series of handprints from the ash coating of his family’s fire.

Boy Here, Boy There is full of contrast. There are pictures full of light and others bathed in darkness. Humans work hard and rest. The boy integrates his surroundings into his vision of the world. Finally, and accidentally, he encounters a glimpse of the future.