The History of Jerusalem: An Illustrated Story of 4,000 Years – written by Vincent Lemire, illustrated by Christophe Gaultier, coloring by Marie Galopin, translated from the French by Amanda Axsom

Abrams ComicArts, 2024 (originally published in French, Les Arènes, 2022)

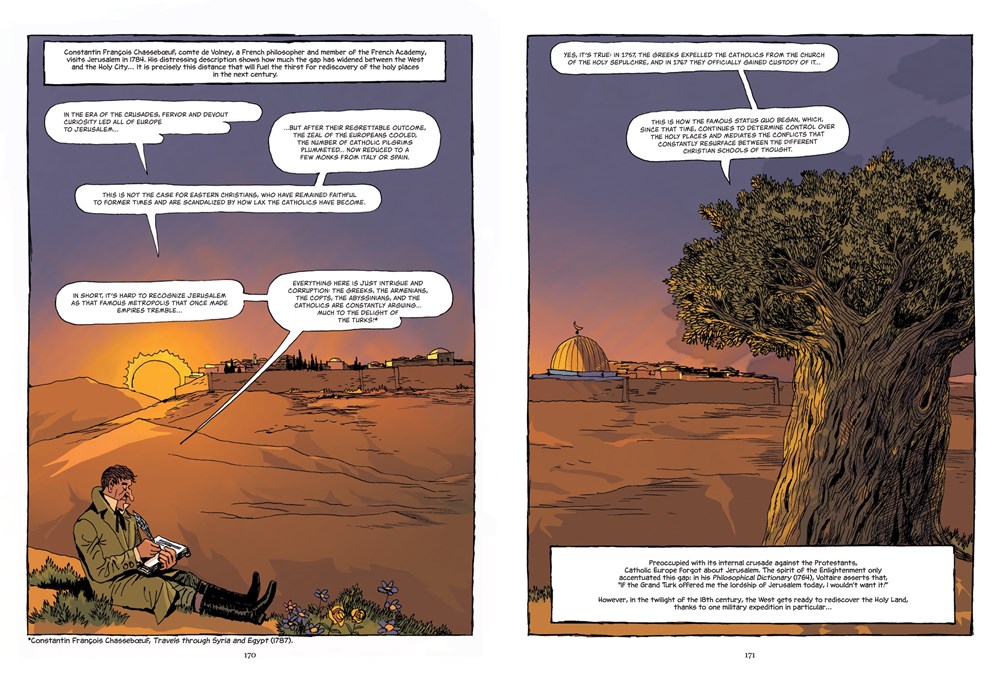

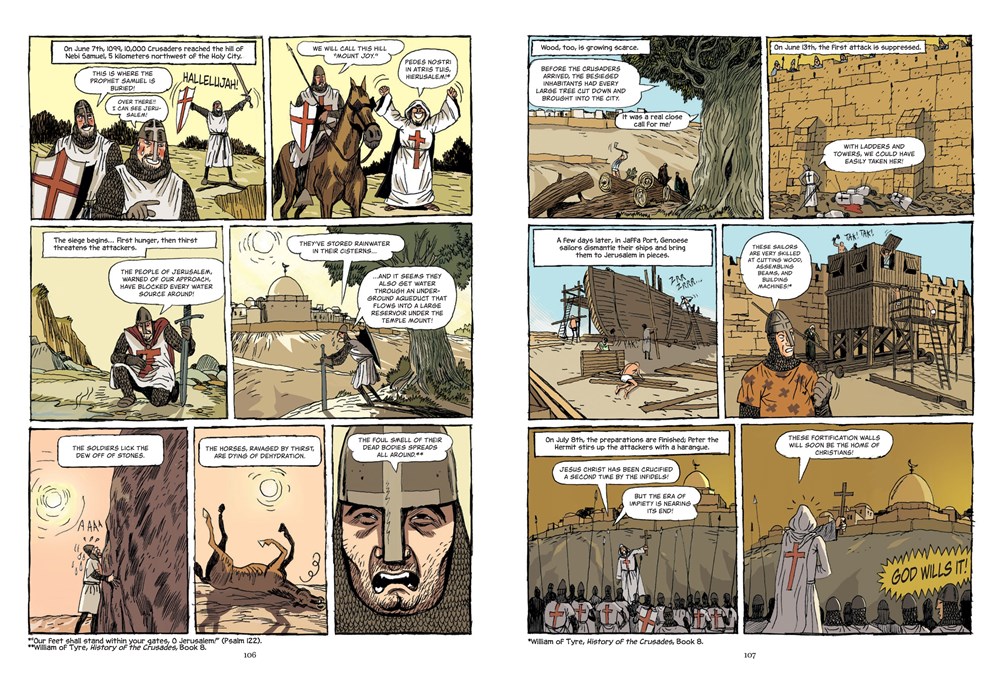

The narrative premise of this graphic history is that a 4,000 year-old olive tree is uniquely placed to teach readers about Jerusalem’s contested past. If that seems an unlikely approach, its success is only one of the many surprises in this unusual book. Dense with facts, yet a at the same time utterly absorbing and swiftly paced, The History of Jerusalem is also both provocative and balanced. The illustrations allude to classic comics, while subverting the idea that anyone involved has superpowers. Even great historical figures, and mythical ones, are viewed realistically, from different angles. It would be impossible to interpret the history of this city without controversy; Lemire and Gaultier do not avoid that essential truth. Instead, they maintain an appropriate level of respect and skepticism about both the past and the future. The book may be intended for adults, but it is equally appropriate for young adult readers, and would be an excellent complement to other, more ideological, resources.

The opening image of the tree, Zeitoun or Olivia, promises some divisiveness, or perhaps coexistence. After all, the word bubbles proclaim “Hello!” “Shalom” and “Salam!” She lays out the vast panorama of the city, echoing the biblical tale of creation: “In the beginning, when this story started, there was nothing…” Then the nothingness fills with geography, history, religion, ethnic groups, famous and influential people who impacted Jerusalem’s move towards centrality. Vincent Lemire chooses each event with great care, allowing different perspectives to emerge. There are events so loaded with meaning that their inclusion may seem unnecessary. The near sacrifice of Isaac, or Jesus at the Last Supper, command an immediate, probably pre-determined response. Yet they are equally weighted with panels dedicated to other hinge moments. The correspondence between former Arab mayor of Jerusalem, Yousef al-Khalidi and Zionist leader Theodore Herzl also reveals world-changing consequences. Christophe Gaultier depicts the serious and careful intent of Khalidi, seated at his desk with inkwell and steaming cup of coffee. When he writes to Herzl, “The concept of Zionism in itself is beautiful…My God, historically it is indeed your land,” the future appears in one way. When he follows those words with “We Arabs and Turks view ourselves as guardians of Jerusalem’s holy places…in the name of God…leave Palestine alone!” that future veers in a different direction.

The presence of each group taking root is documented. Lemire emphasizes both biblical accounts whose literal veracity can be disputed, and abundant archeological evidence of an ongoing Jewish presence, including autonomous kingdoms. Hellenistic, Roman, and Persian domination never erased a Jewish presence, nor did the western Christian Crusades, dedicated to brutally removing the Islamic control of the Holy Land. The rich Islamic civilization that developed from the mid 7th century C.E. eventually regained power and flourished under the Ottomans, until British victory in World War I brought it to an end. While there were continuing struggles for power throughout the centuries, Lemire seems to suggest a relatively equitable sharing of space by Jews, Christians, and Muslims, until the British Balfour Declaration promoted the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. This assertion does not seem to be based as much in contempt for Jewish aspirations, as in an overly idyllic view of the region prior to the British mandate.

It is impossible to summarize the book’s depth, and sensitivity to the competing claims that inevitably threatened any permanent harmony. But at every point when I began to sense bias, the author provided counter examples. The exclusion of refugees from the Holocaust, the refusal to accept partition by the U.N., and other obstructions to a successful resolution are mentioned; blame is apportioned among the British, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, and extremist elements on all sides. I felt uneasy at the faint implication that “Ashkenazi” Jews were somehow less indigenous to Jerusalem than Sephardim. The reference to Yasser Arafat’s “moving speech” at the U.N., in light of his extreme corruption, is, at best, ingenuous. Yet these are relatively minor exceptions to the tone of generosity and hope. A book with this range could not avoid controversy and still attempt complexity. Lemire and Gaultier construct a solid edifice built on fact, myths, and deeply held beliefs. They refrain from assigning unique blame to anyone, and also avoid judging the validity of Jewish conviction that the modern state of Israel represents self-determination. The lonely olive tree holds out hopes for a reasonable solution, of “two independent but allied states” built on mutual respect.