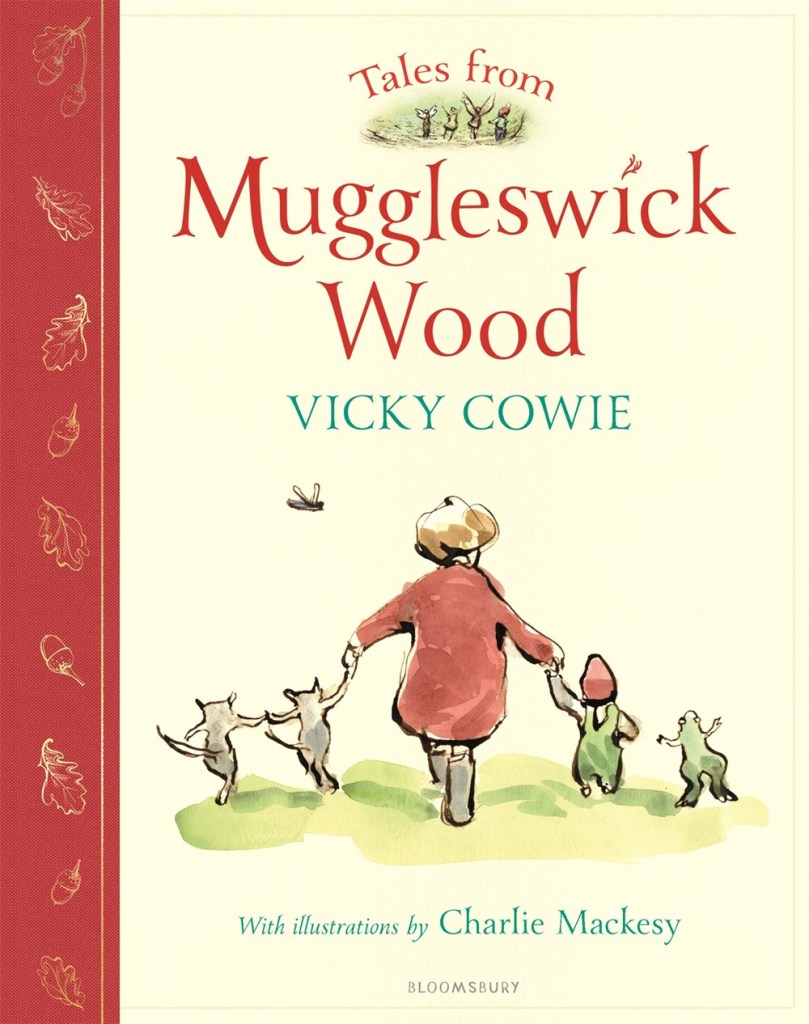

Tales from Muggleswick Wood – written by Vicky Cowie, illustrated by Charlie Mackesy

Bloomsbury Children’s Books, 2025

Nostalgia sometimes carries a negative implication. When applied to culture it can imply that an author, artist, or film maker is steeped in the past to the exclusion of present realities. Tales from Muggleswick Wood is not vulnerable to that accusation. While this delightful collection of five stories is certainly an homage to older classic tales, it is also a lively and artistically distinguished work. Whether or not young readers are reminded of Winnie the Pooh and the Hundred Acre Wood, Brian Jacques’s Redwall series, or Jill Barklem’s Brambley Hedge, they will be entertained and educated.

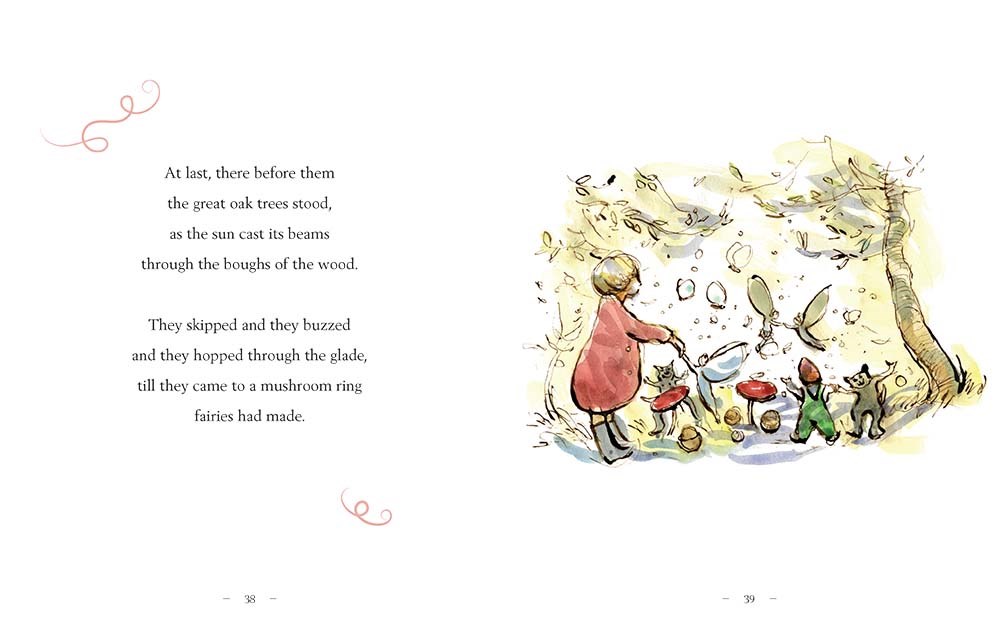

The book’s endpapers feature a detailed map, by Kathryn Rathke, of Muggleswick. This includes not on the woods of the title, but the village, grange, mere, and other settings which will appear in the stories. Vicky Cowie’s clever rhyming text recalls its roots in British and American children’s books, as would be expected, since the framing device of the narrative is Granny’s tales, told at her grandchildren’s request. “The Magic of Muggleswick Wood” opens with a portrait of the characters holding hands, their backs to the reader. The girl and her gnome friend, Neville, share a Christopher Robin and Pooh companionship, although Neville is somewhat less naïve than Pooh, which is helpful when gargoyles and a fairy ring appear.

The stories are not uniform in tone. “The Biggest Blooming Beetle” has an outsized insect rather than fairies, and “The Secret of Snittington Hall” returns to the supernatural in the setting of a grand home. “A magical brownie of secret descent” is a helpful friend to Lady Plumcake, asking only for porridge and honey in return for his efforts. Nonetheless, an ill-treated brownie can quickly transform into the much less pliant “beastly boggart.” “Kevin the Kelpie” explores the dangers of relying on the title character for transportation, if you are an imp, gnome, or wood nymph requiring a ride to the Big Blackthorn Bash.

Charlie Mackesy‘s ink and watercolor illustrations, like those of Quentin Blake and Edward Ardizzone, use caricature, ranging from gentle to somewhat frightening. Each character’s distinctive traits emerge from delicate brushstrokes and changes in hue. Mrs. Plumcake ponders how to respond to rude Mr. Pratt, her arms crossed and world bubble above her encasing the essential items: honey, a horseshoe, and a ten-pound note. Fairies and gnomes are easily identified from their roles in folklore, but not limited by them.

Perhaps the darkest tale in the book, “Melvin the Mole,” relates the problem of Major Hugh White, who is plagued by a bothersome mole in his garden. Melvin has “teeth like daggers,” but also a “soft velveteen” coat. Is he a pest or simply a creature caring for his family? Major White is convinced of the former, and engages a “professional mole catcher” by the name of Mr. J. Thatcher. Before describing the type of caricature used to depict him, I would like to state categorically that it is certainly unintentional on Mr. Mackesy’s, or Ms. Cowie’s, part:

Mr. Thatcher was thin, a grim sort of chap,

with a long moleskin coat and a matching flat cap.

His curly red sideburns came right to his chin,

and he smelled like the juice of a week-old dustbin.

Mr. Thatcher bears a marked resemblance to both Shylock and Fagin. Each quality in isolation would be much less resonant; it’s the combination in one image that brings to mind antisemitism tropes. To place him in context, his exaggeratedly long nose is only slightly longer than Major White’s. His flat cap might be worn by anyone, but as part of the total costume, along with the long coat, sloping brow, and especially the red sideburns, it is difficult to separate each suggestive element of the drawing. Some Orthodox Jewish men and boys wear long sideburns, payot, or payes, in fidelity to Jewish law. While an adult Jewish man who wore them would most likely also have a beard, they are still an unmistakable signifier of Jewish identity. The reeking of filth is another alleged Jewish quality, rooted in the Middle Ages, but prevalent in 19th century Europe. There is a picture of Mr. Thatcher pointing at a sign advertising the noxious refuse he will use to destroy moles. In this picture his features are even more exaggerated, his eyes hooded and his nose enormous.

This one section of the book did not, however, compromise its value for me. It is a beautiful work of art for children deeply imbued with respect for the literary past and innovation in the present. We are all vulnerable to stereotypes communicated in childhood, and I am sure that is explanation for their appearance in this wonderful book.