My Lala – written by Thomas King, illustrated by Charlene Chua

Tundra Books, 2022

My Lala celebrates one of the most endearing misconceptions of childhood. When toddlers decide that they are the center of the universe, and own everything that surrounds them, they might come into conflict with other family members or classmates. But Thomas King and Charlene Chua choose to celebrate the glorious recognition by one little girl that she owns the world. By focusing only on her, and the red dots that identify all her possessions, they interpret this state as one of pride in a growing autonomy. The book is funny and tender, with a rhythmic text and bold graphics. Children and adults will both relate, from different angles, to Lala’s joy in taking control.

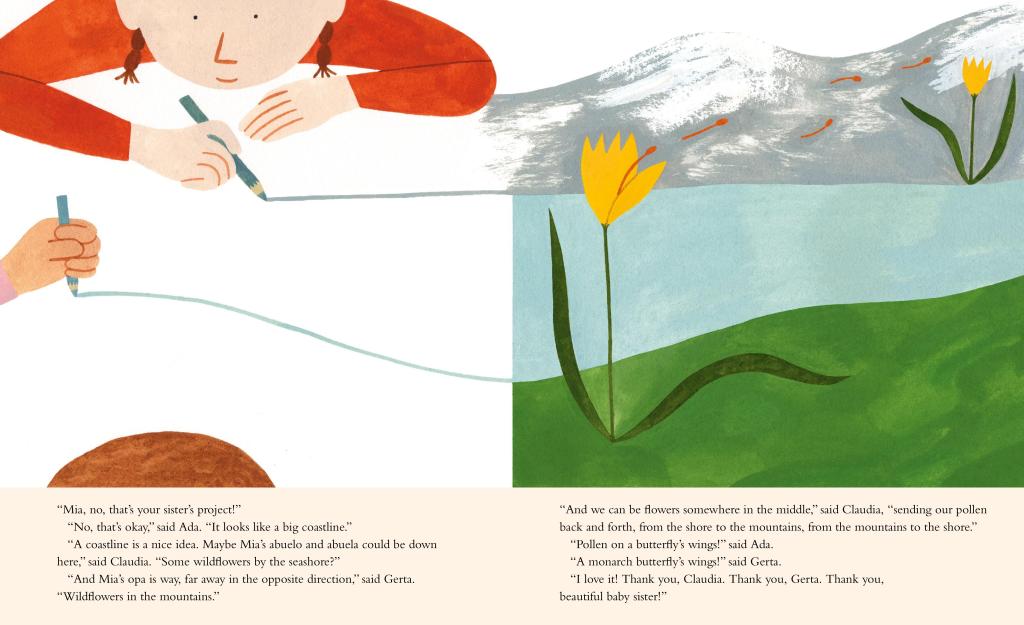

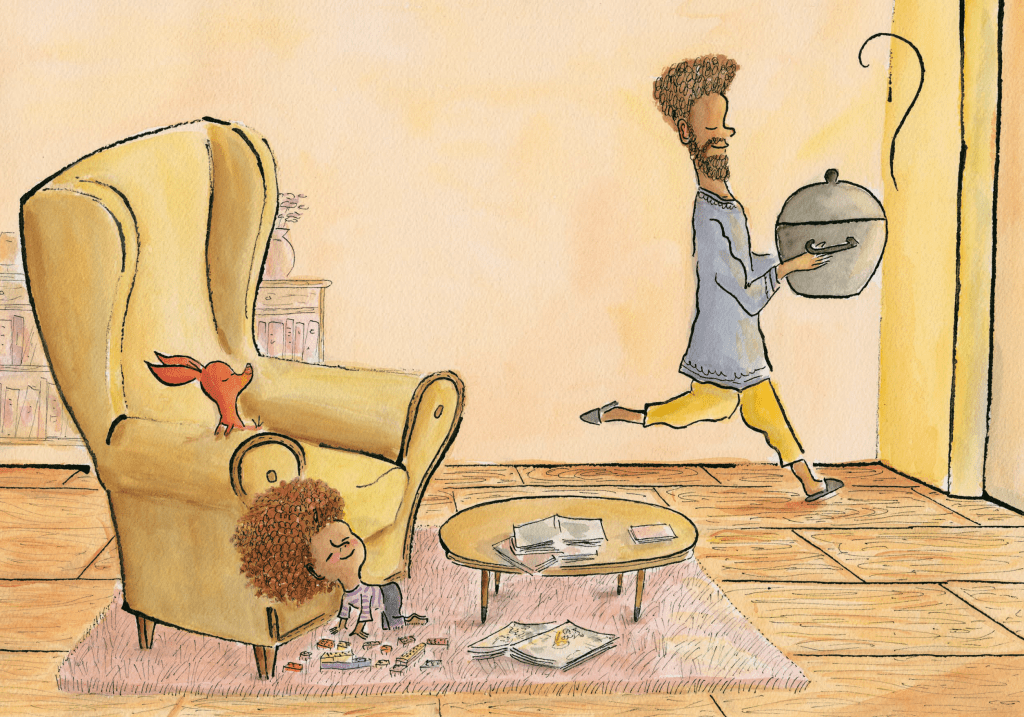

Lala both collects and creates red dots. They open and close the endpapers of the book, and mark every page in between. Lala’s sense of self-awareness begins when she wakes up one morning with a sudden epiphany: “One morning when morning came bright as a pear,/Lala decided that she owned the world.” Note that King describes this development as a decision. Lala is happy, determined, and energetic. Her animal costume pajamas suggest a small creature in the wild, but she is not reckless. King and Chua depict childhood play as looking chaotic on the surface, but actually governed by purpose. Her Lala box is magical and stuffed with treasures.

She uses the dots to identify and claim special objects, from blankie to book, to the bright yellow raincoat hanging on a hook. In addition to affixing the red dot to each item, she awards them her own name: “One for My Lala blankie and My Lala book.” Lala tries on clothes to prepare for the weather. She tapes a red-dotted pirate hat on her hapless cat.

Naturally, she is an artist, clutching the markers that she uses to transform her bedroom walls into a gallery. Each picture shows the excitement of a child transforming her small stature relative to adults into an asset, by inhabiting every inch of space without inhibitions. There is only one time in life when this is allowed; King and Chua let children know that it is a wonderful opportunity.

Resources are finite, but Lala doesn’t know that. In fact, when she runs out of dots, this temporary obstacle inspires her to action. Her coloring, snipping, and pasting are filled with frenetic energy, as she dances from page to page. The constant motion in this book is like a dance choreographed by a child. King and Chua convey complete empathy with Lala’s project, while maintaining the slightest distance from her perception of the universe. Lala’s insistence on ownership has no sense of envy, fear, or anger. She simply loves every article in her life and expresses that happiness in a bright, red dot. My Lala captures that fleeting stage with simple perfections.