Eat, Leo! Eat! – written by Caroline Adderson, Illustrated by Josée Bisaillon

Kids Can Press, 2015

Here is a lovely and inventive picture book about grandmothers, stories, food, and the specific appeal of pasta. Just like the staple of Italian cuisine, which comes in many different shapes, Nonna’s stories for her grandson, Leo, are varied and delightful. Believe it or not, Leo isn’t such an eager customer. Sometimes he’s just not hungry. But his grandmother, Nonna, turns every type of pasta, from star-shaped stelline to the menacingly named occhi di lupo (wolf eyes), into a pretext for exciting narration. Although the pretense of the book may seem elaborate, Caroline Adderson’s conversation tone and Josée Bisaillon’s friendly pictures (link to other blog post), make this family story as inviting as a bowl of zuppa.

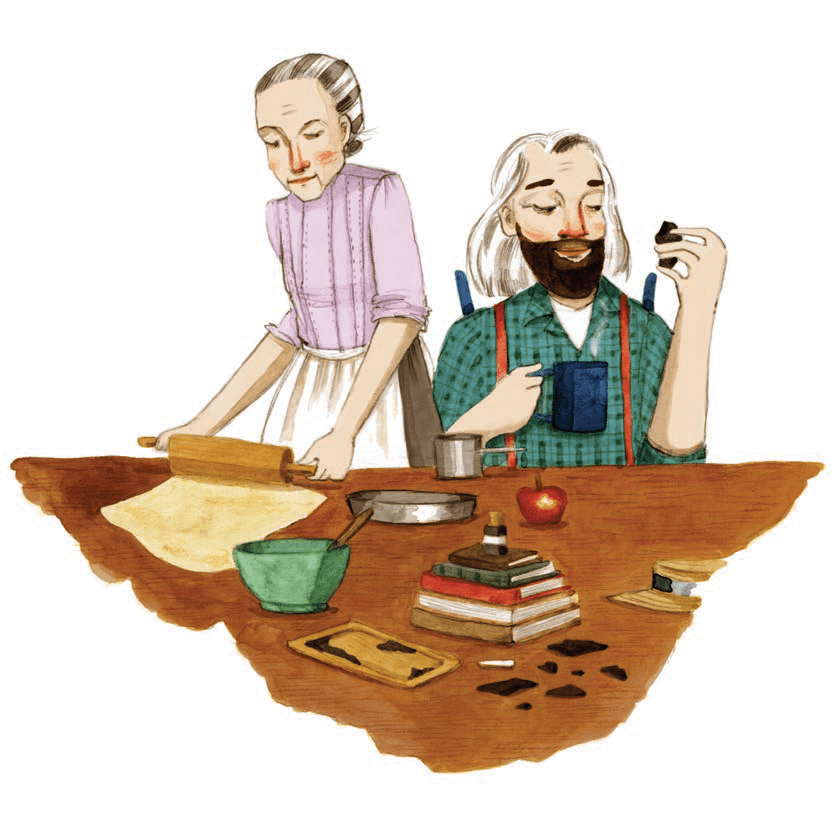

The book opens with a child’s eye view from the kitchen floor, as adult feet stand in place to socialize or walk swiftly to get the gathering started. Nonna would like Leo to eat, but she isn’t pushy. Her gray hair and big glasses and her resemblance to Leo’s mother make her seem comforting. She’s also smart and imaginative, ready to entice Leo with the first of a series of tales. Each week a young boy undertakes an adventure, its outcome unsure enough to be a bit scary. Once he uses spaghetti to tie up a wolf, another time a thousand colorful farfalle, butterflies, appear in the sky. Leo’s extended family, both children and adults, are equally absorbed in Nonna’s magic.

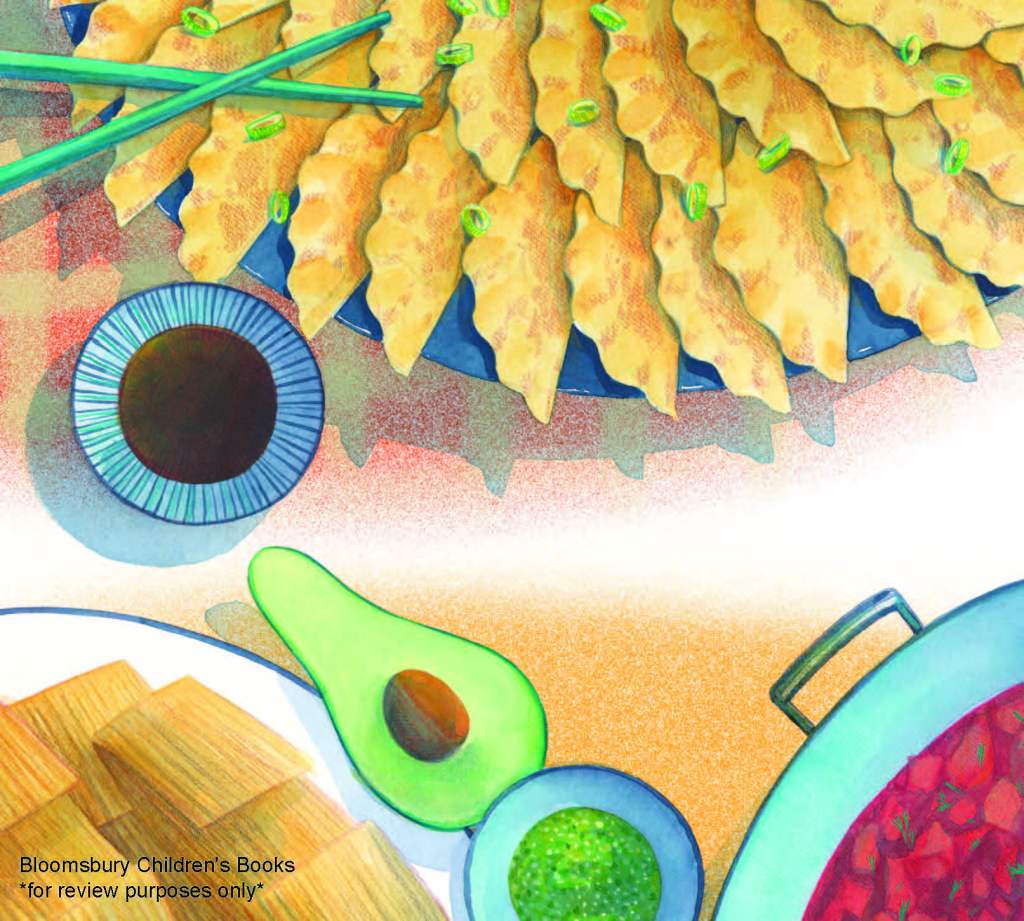

Bisaillon’s pictures are her inimitable blend of realism and exaggeration. Bodies and faces are slightly stylized. Some scenes are viewed at an angle or from above. Nonna’s kitchen is full of detail, from multicolored stacked bowls to dishtowels hanging from the oven’s handle. Jewel tones and pastel colors alternate, as do dark and light scenes. The tone is casual, preempting any sentimentality that might be expected in a story about an ethnic matriarch and her clan. There’s even an afterword, “A bit about pasta,” explaining the amazing range of shapes available for this food, and a glossary of Italian words appropriately placed at the beginning of the book. Eat, Leo! Eat! is a feast of words and pictures.