The Smile Shop – written and illustrated by Satoshi Kitamura

Peachtree Publishing, 2020

A young boy in a bustling city is excited, because he has saved enough money to buy himself “something for the very first time.” The reason for his happiness may be the desired purchase, or perhaps the experience of independence itself, but he is going to savor his trip through the street market before deciding how to spend his money. Satoshi Kitamura evokes the sense of a child’s new freedom, his disappointment when an accident occurs, and the realization that, sometimes, the best things in life are not an expensive toy boat. The Smile Shop gives the sense of both a classic fable and a modern tale of endless choices in urban life. At the end, readers understand that, while the boy’s wish for something new was not trivial, his ability to adjust to circumstances was more meaningful and fulfilling.

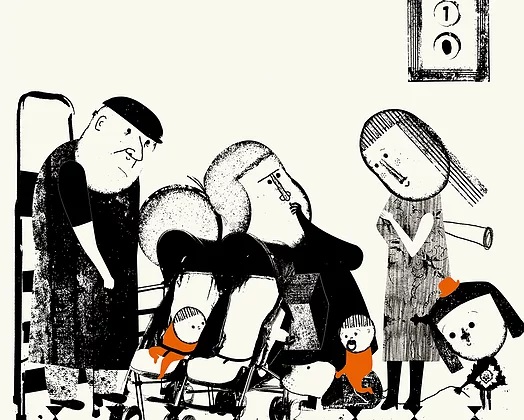

There’s a timeless quality to the book. The multicultural city residents wear contemporary clothes. As the boy walks among them, his dark blue sweater and matching boots, and his bright red scarf, cause him to stand out from their gray, brown, and pastel forms. He might be a boy in a fairy tale, or Harold among the creations of his purple crayons. Kitamura’s unmistakable choices for the market’s wonders are not disposable. Instead, the boy is attracted to such serious items as a wonderful-smelling soup , an analog clock, and a finely crafted musical instrument. Young readers may recognize that there are no video games or even sports equipment among his possible choices.

Once his money falls down a street grating, we are in the territory of easily identified disappointment. How did that happen? Was he distracted by too many possibilities? The book then slips from reality to possible fantasy, as the boy enters a shop labeled “Smile.” There are portraits of smiling people on the wall, but the owner at first appears quite serious. In fact, the element of caricature in Satoshi’s drawings, as well as his three-piece suit and bowtie, gives him an intimidating demeanor. After the non-monetary exchange takes place, the boy has been enlightened. Even the economy of the street is transformed, as the search for ordinary goods and services becomes a celebration, with music, dance, and conversation. There is no heavy-handed moralizing about materialism or greed, just an appealing and subtle illustration of ideas. Disappointment is part of life, distraction can lead to mistakes, and people need more than a fancy toy boat or a gourmet meal to be happy.