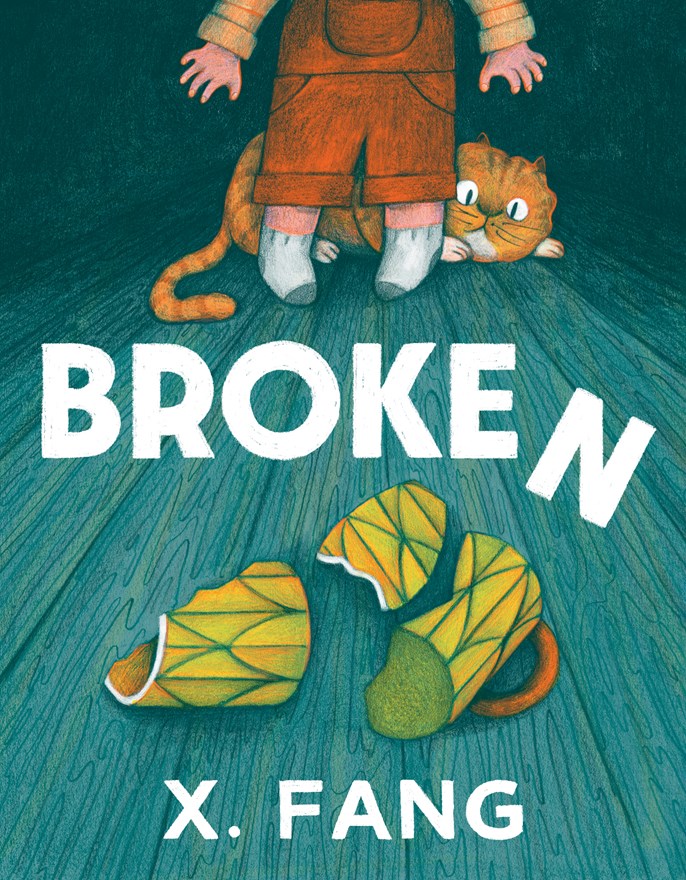

Broken – written and illustrated by X. Fang

Tundra Books, 2025

A picture book by X. Fang has an unmistakable identity (see my reviews here and here). The actual species of the mysterious visitors in We Are Definitely Human may be ambiguous, and the vivid dream imagery of Dim Sum Palace seamlessly transforms to the warmth of a family restaurant. Broken is about the unbreakable bond between a grandmother and her grandchild, and also the reassuring truth that many things that are broken can be repaired (grandparents being a constant presence in children’s books, as seen in my list at the beginning of this review). Maybe the new object will appear identical to the old one, or perhaps some small difference will be evidence that its importance is not compromised by a beautiful, jagged crack and some glue. The sturdy, rounded characters who populate Fang’s earlier books are back, but they are not repetitive. She has a specific visual interpretation of humanity and it is inimitable.

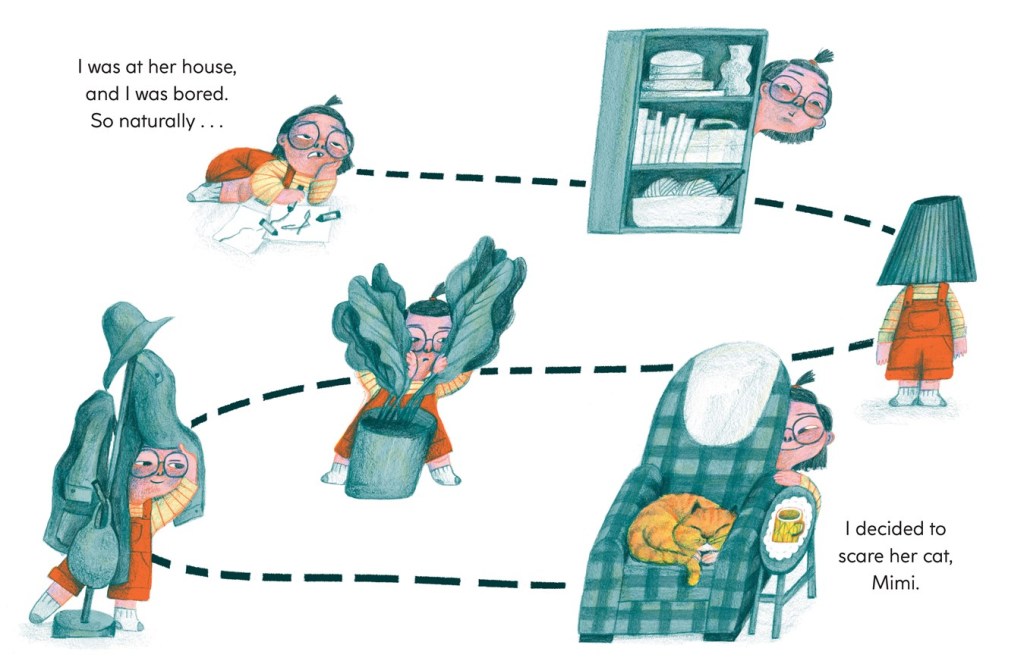

A little girl, Mei Mei, introduces the story with an invitation and an outright confession: “Let me tell you the story of the day I broke Ama’s cup.” A day at Ama’s house is full of unspoken comfort, but sometimes boredom. Thick dashes connect the girl’s activities, like a familiar board game.

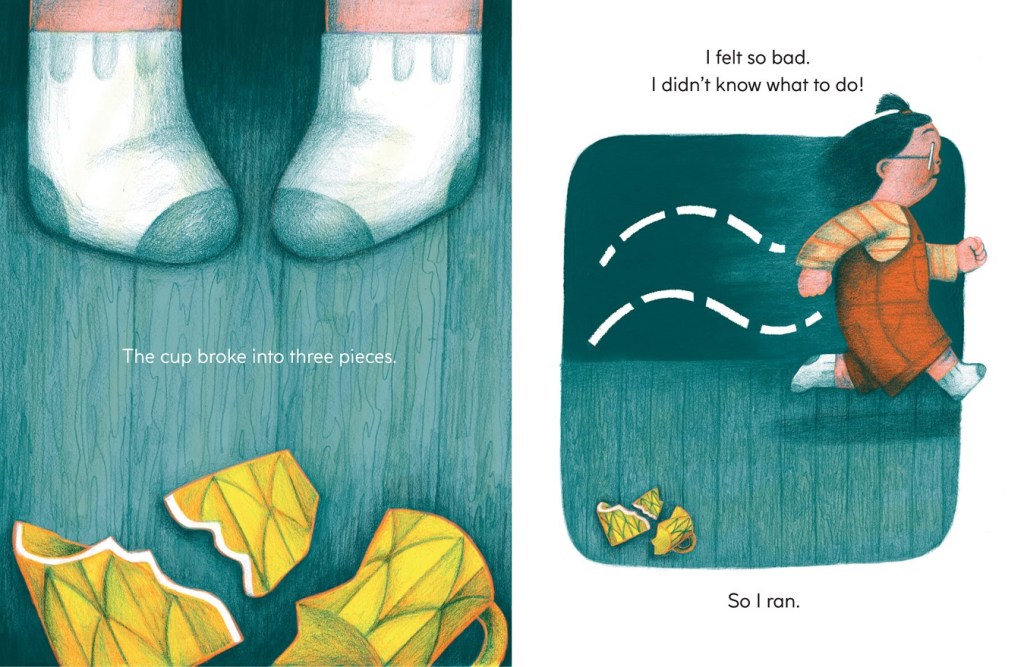

Then it happens. Having made the conscious decision to frighten Ama’s cate, the girl bumps into a table and hurls the cup towards its trajectory. Not only does it break, but the damage results in three pieces. Appealing to young readers with a direct statement of her guilt, the girl futilely tries to escape her own fears. What if Ama’s unconditional love has conditions attached?

The girl’s senses become exaggerated. Her grandmother calls to her, maybe in anger. That may seem unlikely to an adult reader, but only her warm smile convinces Mei Mei that nothing fundamental has changed. Ama brings her some cake. Mei Mei has the opportunity to blame the broken cup on the hapless cat, but she can’t bring herself to be dishonest. A full page picture of the cat’s accusatory stare is the counterpoint to Mei Mei’s closed eyes behind her oversized glasses.

Overcome with anxiety, she hides in the closet, obviously a temporary solution. Fang even includes a helpful graphic of Mei Mei in silhouette profile, the truth emerging from her insides in arrows that turn into words of apology.

Mei does not only forgive her; she offers an explanation. Repairs make meaningful objects stronger. Each one tells a story. Ama takes on a new identity, as a “fixer,” in a series of portraits framed with old-fashioned photo corners. She is a super competent, and also compassionate, role model to her beloved and unique granddaughter.