Fantastic Lou: Little Comics from Real Life – written and illustrated by Qin Leng

Tundra Books, 2025

All good children’s books are also good books for adults, but some seem specifically designed for both audiences. Qin Leng’s graphic chapter book, picture book, or collection of “little comics,” is definitely in the latter category. The cover, with a brightly smiling child radiating assertiveness, alludes to some of the mid-twentieth century comic classics. The wry interpretation of parenting issues also brings to mind the work of Liana Finck. Yet Fantastic Lou is also fantastic for children, reflecting their thoughts and feelings about everyday situations and important relationships.

The interminable experience of playing a board game is, at the same time, a way to have some quiet and meaningful interaction with a Lou, her child. The existential unfairness, mixed with boredom, might even be irritating to adults. “You fell in a hole. That means you gotta go back to square one.” An adult might feel bereft at that news, but a child’s understandable rage is difficult to dismiss. Leng captures the whole range of responses in her lively and delicate pictures, drawn in ink and digitally colored.

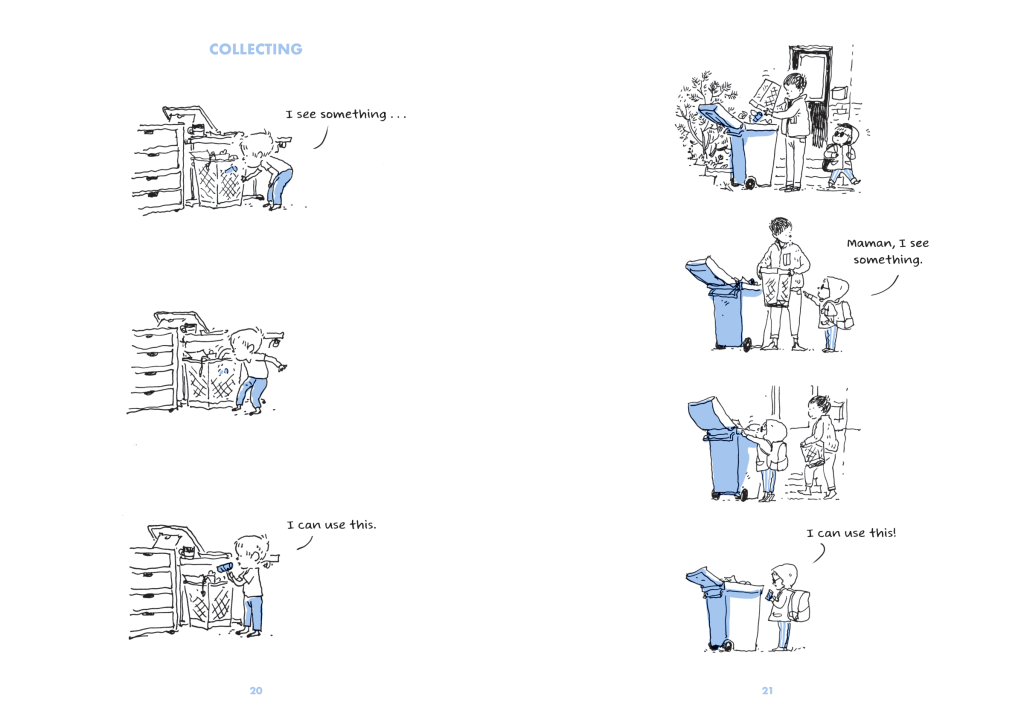

Collecting may have different meanings for children and adults. Leng focuses on how a child finds meaning in an object that seems useless to his parents. Forget well-intentioned recycling. Lou extracts a series of items, explaining the process with clear simplicity. Language also reflects the difference between Lou and Maman: “I see something, Maman. I can use this.” What further justification is needed for pulling things out of the trash? The reader is left to imagine the infinite uses implied in Lou’s artistic vision.

Lou’s image of his future self is as clear as his prospective plans for thrown-away collectible. In “When I Am Bigger,” he divides his life so far into two stags, and projects a third one based on growing size and increased power. After all, that is how adults appear to children. The adjacent chapter, “Montréal Trip,” takes that abstract idea and offers a concrete example of his special status as a child. The prospect of boarding the plane is exciting enough, but, in fact, his small and vulnerable size is granted equal status to the most privileged travelers: “Priority boarding for VIP members and passengers traveling with young children…”

Children are VIPs in Leng’s work. Sequences of constant motion, flights of imagination, and attempts to make sense of adult decisions, add up to childhood itself.