Summer Is Here – written by Renée Watson, illustrated by Bea Jackson

Bloomsbury Children’s Books, 2024

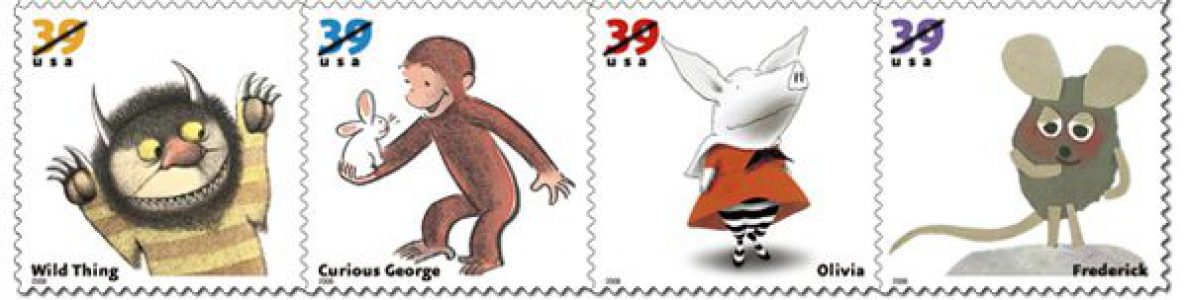

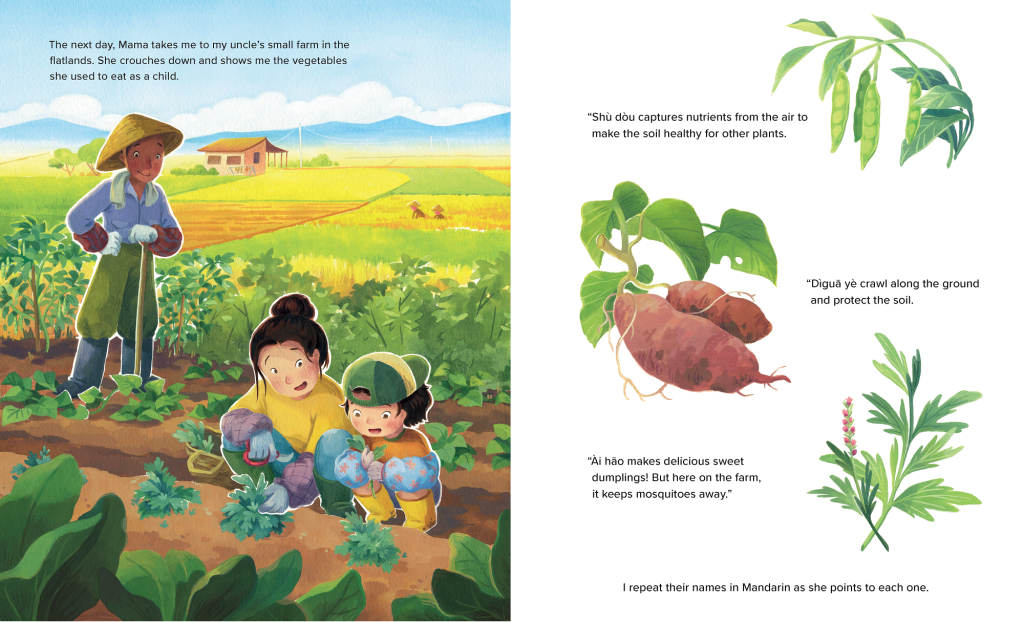

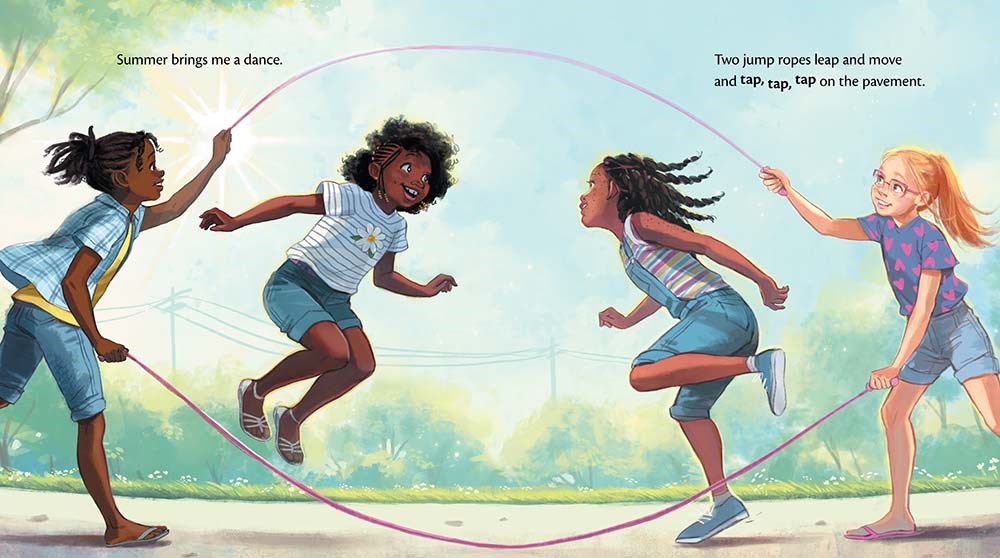

Summer Is Here approaches the arrival of the season exactly the way a child would, with excitement and joy. The text uses simple description, rhythmic language, and a bit of poetry (“Summer sings me a song,/serenading me from the ice-cream truck.”). Renée Watson gives voice to a young girl, allowing her to choose what is most significant: the ephemeral fun of blowing bubbles, swimming with friends (image), time spent with a loving family, and the tinge of regret that comes with knowing that it cannot last forever. Bea Jackson’s digitally created pictures, almost trompe l’oeil in their vividness, are as accessible as the text.

The book’s characters are realistic representations of diversity, of age, race, and body type. There are babies, children, and adults, with larger and slimmer bodies. One girl wears glasses, and style choices include a ruffly peasant blouse, overalls, and jeans. Perspectives change; one two-page spread of a family barbecue gives the father most of the space as he grills burgers, while the facing page shows the girl in the foreground watching him. Other family members sit at a picnic table in the background in a gauzier, less-defined image. Friends float in a pool. What matters most to a child can change from moment to moment.

The concluding scenes of nighttime are a shift in tone, as the lively momentum of summer draws to a close. Summer is personified as female: “I feel her breath blowing/through my open window.” Sitting on the bed in almost balletic pose, the girl looks out at the moon, and, in the next scene, whispers goodbye. The daytimes unique to the season are coming to their inevitable end. Children intuitively realize that some things they love are transient. The warm weather and freedom from structure come once a year, but the foundations of friendship, family, and imagination itself, are more lasting. Watson and Jackson do not need to state that message explicitly; it comes through as a deep sense of security in their words and images. The girl’s closing wish that “summer would stay” is accompanied by her smile and a scene of homes, with lights punctuating the darkness.