I wrote this article before the latest controversy about Dr. Seuss, and was wondering where to pitch it. However, because Dr. Seuss is in the news again, I decided to publish it immediately on my own blog. No, children should not read books with grotesque racist caricatures. Here I call attention to specific problems in an article that broadly attacks Dr. Seuss for his racism, and specifically lacks context concerning his antifascism and defense of Europe’s Jews. Most authors find that much of their work quickly goes out of print. The early works by Dr. Seuss with offensive images might well have taken that route. Instead, by announcing their decision, Dr. Seuss Enterprises was able to prove they had taken a stand against racism. Now the books are virtually inaccessible to scholars, librarians, or anyone else who would like to study and analyze them, because they cost hundreds of dollars on the secondary market. Readers might not be aware that, for one example, the original edition of Mary Poppins had a chapter called “Bad Tuesday” full of abhorrent racist terms. It has been removed from later editions of the book, with a note indicating that the book has been edited. This might have been a possibility with early Dr. Seuss books. Dr. Seuss’s legacy as someone who truly revolutionized teaching reading to children has not changed. Kids still read The Cat in the Hat, Yertle the Turtle, and the Horton books, while McElligot’s Pool has long faded from view. Nonetheless, it is important to have access to these books in order to assess Dr. Seuss’s full legacy: good, bad, and indifferent.

***********

Historian Deborah Lipstadt has used the term “soft-core Holocaust denial” to describe an insidious trend in modern anti-Semitism. Practitioners of this deception do not outright deny that the Holocaust took place. Rather, they minimize it, trivialize it, and deny it any current relevance. Most Americans don’t think of Holocaust denial and children’s author Dr. Seuss as intersecting at any point. Yet the recent outcry against racism in the author’s work, including the decision to distance his brand from the Read Across America events founded to coincide with his birthday, are granted legitimacy partly by denying a central fact about Dr. Seuss: he was a vehemently outspoken critic of xenophobia, isolationism, and anti-Semitism in the interwar era, when Jews in Europe faced imminent annihilation, and American Jews felt powerless to intervene in the impending tragedy. A recent academic paper, “The Cat is Out of the Bag: Orientalism, anti-Blackness, and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss’s Children’s Books,” by Katie Ishizuka and Ramón Stephens, has become a prooftext in the push to topple Dr. Seuss, like Yertle the Turtle, from his lofty status in children’s literature. Cited widely, from National Public Radio to School Library Journal, and even People Magazine, the paper’s apparent power to convince is largely due to its dramatic distortions of Dr. Seuss’s part in the fight against Nazi race hatred. As in Lipstadt’s description of thinly concealed Holocaust denial, the paper’s authors exploit a declining base of historical awareness to convince readers that Dr. Seuss’s advocacy for Jews was worthless.

The same ignorance of history, which provides a fertile ground for questioning the truth of the Holocaust, has allowed a segment of critics claiming to promote racial and cultural diversity in children’s books to redefine Seuss’s long career. Without a doubt, that career included repugnant racial caricatures of both African and Asian people in his early cartoons for the puerile Dartmouth College humor magazine. Some of his early picture books, including If I Ran the Zoo, reveal similar racist tropes, as do several of his advertisements for products from bug spray to beer. We look at these today and recognize them for what they are: offensive, even disgusting. Yes, this is the same Dr. Seuss who later went on to promote environmentalism in The Lorax and peaceful coexistence in The Sneetches. Long before those popular books reached young readers, Dr. Seuss drew more than 400 cartoons for the leftist New York publication, P.M. This grandson of German immigrants dedicated much of his work to warning Americans about the senseless cruelty of denying refuge to immigrants, and of turning our backs on Britain as that country begged for an end to the outdated Neutrality Acts of the 1930s. In his Fireside Chat of December 17, 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt, addressed Americans reluctant to become involved in another European conflict, arguing that their refusal to allow aid to Britain was like denying a neighbor the use of your garden hose because the fire had not yet spread to your own backyard.

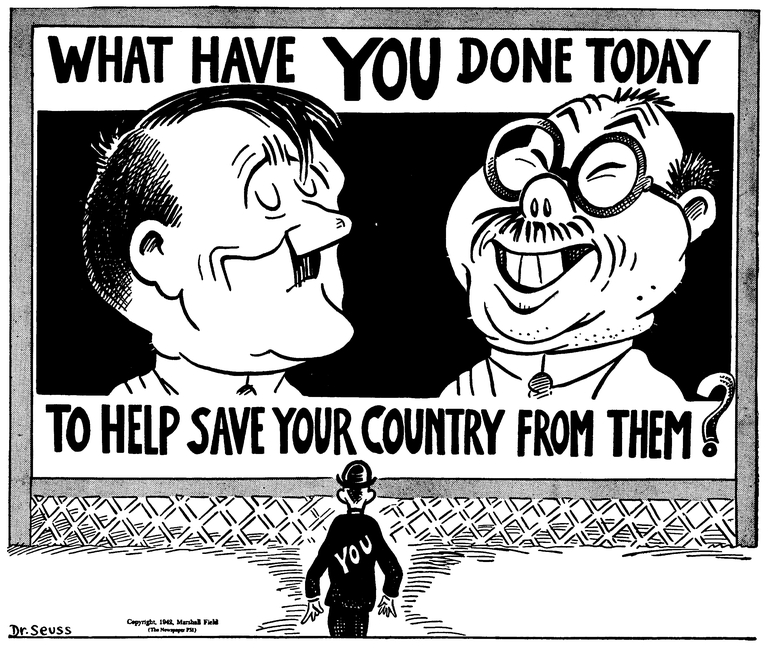

Not surprisingly, Dr. Seuss was funnier than F.D.R. In a rich collection of his political cartoons on two University of California at San Diego websites (viewable here and here), readers can find an artist whom some would not recognize as the same figure currently vilified as a primitive hate-monger. Here are just a few which have earned Dr. Seuss gratitude and respect from Jews:

This cartoon uses a familiar Seuss technique of mixing human and animal qualities, as a sad looking bird with an Uncle Sam hat and beard, sits locked in the stocks associated with punishment in early America. His crime is declared on a sign hanging from his beak: “I am part Jewish,” and his tormenters are named specifically as C.A. Lindbergh and Gerald P. Nye. Lindbergh, the target of Seuss’s contempt in several other cartoons, was the revered American aviator, a heroic symbol of rugged individualism. This same Lindbergh was also the most famous spokesman for the America First Movement, dedicated to promoting isolationism by insisting, as Lindbergh did in his infamous Des Moines speech of Sept. 11, 1941, only eleven days before this cartoon was published, that U.S. involvement in the War was being promoted by Jews. As he warned this disloyal segment of Americans:

Instead of agitating for war, the Jewish groups in this country should be opposing it…for they will be among the first to feel its consequences…The greatest danger to this country lies in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio and our government.

In a much more graphic cartoon registering Seuss’s revulsion at Nazi persecution, Jews hang lifeless from trees, their identity prominently pinned to their corpses. Below them, Hitler and French collaborator Pierre Laval, head of the puppet government of Vichy, are singing joyfully about the ‘sport” of killing Jews. In case anyone missed the point, a noose is casually draped over Hitler’s arm. The dictators are singing a parody of Joyce Kilmer’s poem, “Trees,” a sentimental fixture in American culture at the time.

Pearl Harbor brought the end of American isolationism, but Dr. Seuss had no illusions about the potential for defeatism or for the very racism that Americans were fighting in Europe to damage the war effort:

Here, a racist employer, instead of promoting the full use of the American workforce, defends Jim Crow laws and dangerous prejudices against black and Jewish laborers.

Dr. Seuss also dramatically inverted the age-old stereotype of Jews as disloyal “rootless cosmopolitans,” never committed to any country where they lived:

Here it is “U.S. Nazis,” those Americans still reluctant to view fascism in Europe and Asia as threats to American democracy, who are the real traitors. (See Roger Cohen’s poignant look back at the German American Bund’s anti-Semitic attacks.) One of the tools was American anti-Semitism which, if not as historically violent as its European equivalent, was just one step away from a hooded executioner inflicting the same bloody end on both American Jews and Uncle Sam himself.

Where do these courageous documents fit into “The Cat is Out of the Bag,” and its authors’ firm conviction that Dr. Seuss’s role in American history is one of unmitigated evil? It seems that Ishizuka and Stephens realized the need to at least raise opposing arguments in their paper; they claim to have “analyzed Seuss’s early political cartoons…that scholars assert are examples of his anti-racist work.” They then mention three anti-racist cartoons in which Dr. Seuss argued for encouraging the full use of both white and black labor during the war. According to Ishizuka and Stephens, these cartoons, rather than crying out for racial equality, are actually “political propaganda geared toward exploiting Black bodies for the purpose of the war effort.” To strengthen their argument, they grossly distort the work of other Seuss scholars. Charles Cohen, in his 2004 biography, The Seuss, the Whole Seuss, and Nothing But the Seuss,” offers many details about Seuss’s advocacy of a racially integrated workforce. Ishizuka and Stephens cite Cohen’s book as testifying to Seuss’s real motive, “boosting the capacity of the war industry.” If fact, Cohen describes Seuss’s pre-War obsession with convincing Americans to empathize with foreigners, as well as his transition, during the War, to promoting American values of equality along with the practical motive of defeating the Axis. By summarizing this method as “boosting the…war industry,” they are, ironically, echoing the logic of the Nye Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry, the notoriously isolationist Senate group which warned of the role of war profiteers in promoting intervention in Europe’s conflicts.

In addition to omitting any references to Seuss’s many other cartoons promoting the values of democracy, the dangers of defeatism, and the selfishness of indifference to refugees, they deliberately ignore any of Seuss’s advocacy for Jews and his stubborn persistence in equating the American brand of anti-Semitism with Nazi hatred. Yet, earlier in the article, they do mention Jews. In analyzing material from Seuss’s work for the thoroughly racist Jack-o-Lantern, Dartmouth College’s humor magazine, they describe in detail cartoons with crude anti-Semitic references, such as Jewish football players ransoming a ball for money. Clearly, Seuss’s political beliefs and emotional maturity had both evolved since his college days. Ishizuka and Stephens have consciously chosen to exclusively present evidence of Seuss’s early prejudices, and to omit his much more extensive and influential defense of embattled Jews later. In order to negate any value in Seuss’s life and work, they need to deny the validity of the Holocaust within the history of racial atrocities which form the basis of their argument.

One of the most serious charges against Dr. Seuss was his indefensible support for Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, implementing the notorious policy of imprisoning innocent Japanese Americans because of unsupported allegations of potential espionage. Although a majority of Americans did not question this policy, the very nature of Seuss’s progressive stands on other issues makes his failure to show empathy and courage in this case even more disappointing. However, Seuss’s critics, in order to denigrate his full career, have conflated his racist attitudes against Japanese Americans with his tenacious warnings about the Japanese government and military. After American entry into the War, Seuss continued to draw caustic and bold caricatures of the Axis powers, including the Japanese and the Germans. Granted that the line between racial and individual caricature can be dangerously blurred, is this March 5, 1942 cartoon, showing Hitler and Tojo as a double menace, racist?

Only by thoroughly distorting history can Ishizuka and Stephens hold Seuss guilty for aiding the U.S. war effort. Incredibly, they characterize Seuss’s propaganda on behalf of the U.S. and its allies as examples of “white savior” narrative. Many scholars and readers have interpreted Seuss’s Horton Hears a Who (1954) a fable about the value of even the smallest and most insignificant beings, as an implicit response to the devastation caused by the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Ishizuka and Stephens dismiss this approach, complaining that “…Seuss never issued an actual, explicit, or direct apology or recantation of his anti-Japanese propaganda…” The expectation that Seuss would have “recanted” his support for an Allied victory in World War II is absurd, but it succeeds in building the argument that the War itself was immoral. Therefore, any motivation for fighting which was rooted in protecting victims of Nazism and Japanese fascism, was worthless. This would include Dr. Seuss’s attempts to warn of the impending genocide against Jews. The article’s authors neatly reduce any reading of Horton Hears a Who as a defense of the vulnerable to the equivalent of contemporary racism, where “people of color are forced to prove their right to life and that their lives ‘matter.’”

Each reader and educator will have to make an individual decision about Dr. Seuss, as well as about any artist whose ideas evolved over time, even as early prejudices left inevitably ugly stains on his work. How much evidence do we need of compassion and bravery in Dr. Seuss’s political cartoons to ignore the grotesque caricatures of African and Asian people which lurk in some of his picture books and cartoons? There is no simple answer to that question. However, Ishizuka’s and Stephens’ recent article, as well as other attempts to banish Dr. Seuss from the American imagination, do not engage with that paradox. Instead, by carefully excluding a major segment of Dr. Seuss’s long career, his dedication to the cause of protecting Europe’s Jews from annihilation, they provide a textbook example of Deborah Lipstadt’s “soft-core Holocaust denial.” A recent piece recommending Ishizuka and Stephens’ viewpoint, at Teaching Tolerance (a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center), sternly warns us that “It’s Time to Talk About Dr. Seuss.” Indeed it is. Jewish readers might well consider the motives for constructing so unbalanced an image of the author and artist. Without turning away from honest discussions of his work, we can continue to call attention to an unforgettable part of his legacy.

One thought on “Dr. Seuss and the Jews”