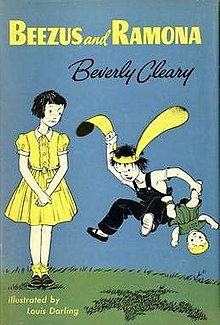

Beezus and Ramona – Beverly Cleary, illustrated by Louis Darling, William Morrow and Company, 1955

Today Beverly Cleary turns 104 years old. It is impossible to overstate her contribution to children’s literature, particularly to middle-grade fiction. Cleary’s characters and stories are timeless because they are based on respect for children, humor, and honesty, as well as an incredible gift for crafting language in a believable way. The permeable line between a sometimes frustrating reality and a child’s imagination is often at the center of her novels. (as can be seen in my previous blogs on her, here and here and here). Her most famous heroine, Ramona, first appears, along with her older sister, in Beezus and Ramona, a sensitive tribute to the fraught relations between siblings.

Ramona is impulsive and stubborn, qualities which often bring her into conflict with adult authority. Yet these same parents, teachers, and other child socializers are drawn to her overflowing imagination. The paradox is difficult for her older sister to reconcile:

At the radio-and-phonograph store, Ramona insisted on petting His Master’s Voice, the black-and-white plaster dog, bigger than Ramona, that always sat with one ear cocked in front of the door. Beezus thought admiringly about the amount of imagination it took to pretend that a scarred and chipped plaster dog was real. If only she had an imagination like Ramona’s, maybe Miss Robbins would say her paintings were free and imaginative and would tack them on the middle of the wall.

Ramona’s imagination often takes the form of explosive actions. She is uncompromising and intolerant of restrictions on her creative powers. The Friday afternoon art class at the recreation center that the girls both attend becomes a free-for-all when Ramona gets into an altercation with a boy who claims that she had stolen his lollipop. Paint flies in the air and lands on children’s clothing. Ramona will not give up and Beezus defends her. Even the beatnik-influenced Miss Robbins, a woman whose earrings “…came almost to her shoulders and were made of silver wire bent into interesting shapes…,” has to seize control. At the same time, Beezus has decided to let go a little, painting a dragon which defies all the rules of realism. When Miss Robbins finally notices this creature who breathes pink candy instead of fire, she is appropriately impressed. It’s not the monster’s pop-art elements, but the fact that sensible Beezus has taken a page from her sister’s book, allowing herself some freedom.

“Here’s a girl with real imagination,” Miss Robbins had said.

A girl with real imagination, a girl with real imagination, Beezus thought as she left the building and ran across the park to the sand pile. “Come on Ramona, it’s time to go home,” she called to her little sister, who was happily sprinkling sand on a sleeping dog.” That would be a real dog, not a plaster one. Sometimes sisters exchange qualities, and sometimes they remain loving opponents. When Beverly Cleary recreates any aspect of childhood, you can bet it will ring true.