Adi of Boutanga: A Story from Cameroon – written by Alain Serge Dzotop, illustrated by Marc Daniau

Eerdmans Books for Young Readers, 2025 (originally published in French, 2019, Translated by the author)

Adi of Boutanga is an important book. That quality would not necessarily make it appealing, let alone essential, to read, but there are many other reasons why it is just that. A voice that resonates with the truth, beautiful illustrations and innovative graphics, a compelling story, and a deep sense of conviction will all enfold the reader in its narrative fabric.

Adi is fourth grader living in a nomadic community, the Mbororos, in Cameroon. Although they are traditionally herders, their economy has changed; Adi’s father transports passengers on his motorcycle and her mother sells Makala (doughnuts) in the marketplace. Adi’s identity is defined by family relationships: “I prefer to stay the big sister of Fadimatou, Zénabou, Youssoufa, Daïro, Souaïbou, and baby Mohamadou.”

Children cannot control their own lives, even to the limited extent that adults are able to do so. Adi loves attending her school, which she describes as a “gift” to the village by Mama Ly and Monsieur, generous benefactors. The process of learning to read may seem inherently magical to many children, but Dzotop captures the poetry of this experience and gives Adi a voice:

Before the school was given to our village, words were invisible to us. We

could hear them, but we couldn’t see or touch them. I even thought a

a strong wind might steal them as soon as they left our mouths. But that

wasn’t true.

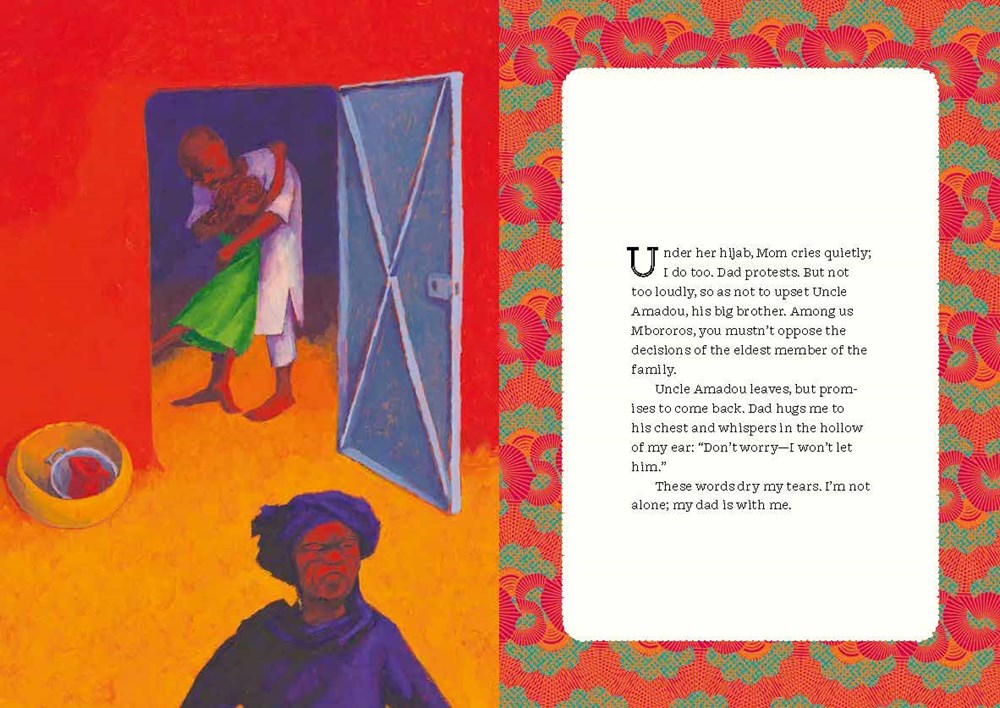

Although there may seem to be a fable-like quality to the book, the characters are not generic. Adi’s mother embraces her daughter’s individuality, responding to Adi’s frequent laughter with the suggestion that her daughter has “swallowed a thousand weaverbirds.” But the warmth and protectiveness of Adi’s life is shattered when her uncle arrives to inform the family that, although still a child, she must marry. Her father and uncle assume opposite patriarchal roles, one caring and the other transactional. “They throw words at each other. Words that hit like stones.”

Saving their daughter means that Adi’s parents must send her away. She goes to Boutanga, where her benefactors have established a school for girls that fosters creativity and dignity. Even if this solution is not a global one, it is enough for Adi and an example for all. Eventually, when she has arrived at the point in her young adult life when she is able to choose, Adi finds love with a man who respects and understands her. Mastering language has been a key to her growth, “catching words… putting them in the right order and making sure they say the right thing.”

The book is not composed only of words, but of images that organically emerge from the culture which they represent. Pages with illustrations alternate with blocks of text set against traditional fabric patterns. Human figures allude to sculpture but have kinetic movement. Earth tones are the setting for the book’s quiet drama, with deep blue sea and red skies framing Adi’s journey. Adi of Boutanga is not a moral lesson, but a work of art that interweaves modern aspirations of freedom for women with the unique threads of a specific culture. It is a book to read, share with children, and read again.