An Anishinaabe Christmas – written by Wab Kinew, illustrated by Erin Hill

Tundra Books, 2024

Finding a children’s book that may be identified as an instant classic is not to be taken for granted. One book that fits that category is An Anishinaabe Christmas. It brings to mind Dylan Thomas’s A Child’s Christmas in Wales, the versions illustrated by both Edward Ardizzone and Chris Raschka, not because of any direct similarity, because the books are very different. Both classics evoke a particular, but also universal, immersion in childhood. You leave the book, and return to it, with a feeling of peacefulness without sentimentality.

A young child from an Indigenous community is going with his parents to visit their extended family on the reservation. It is winter solstice, an inseparable element of their culture’s celebration of Christmas. Baby, as he is called in the book, looks serious, even puzzled, as his mother and father bundle him up and get ready for their car trip. Their evident excitement is in contrast to his hesitation; this experience is typical of childhood. He is concerned that Santa will not find him away from their home. The cultural signifier of this gift-giving figure so common in the West then transitions to the specific deep roots on the Anishinaabe people.

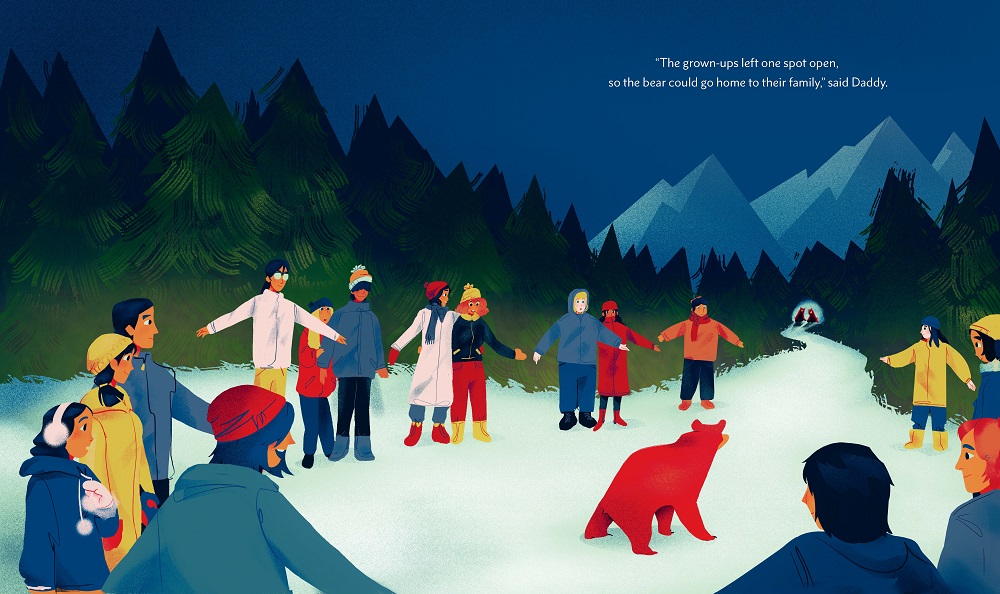

As they drive from the city to the country, the family passes a sign warning not to feed the bears. This prompts a memory that connects Baby to her heritage, and to the natural world that is part of it. Her father repeats the story of how he and other adults had formed a protective circle so that a lost bear cub could find its home. The idea of communalities between humans and animals is organic to the picture, without any ideological explanations. “The bear has a family?” Baby asks. Of course it does, and the father not only answers, but uses the opportunity to introduce words in their native language. (Wab Kinew includes these terms in a glossary at the end of the book, along with an explanation of the cultural syncretism combining Christmas with Indigenous traditions.) The bear also has makwa, family, although it is distinct from the human one. The bears’ makwa will “snuggle up in their dens with their babies for Christmas.”

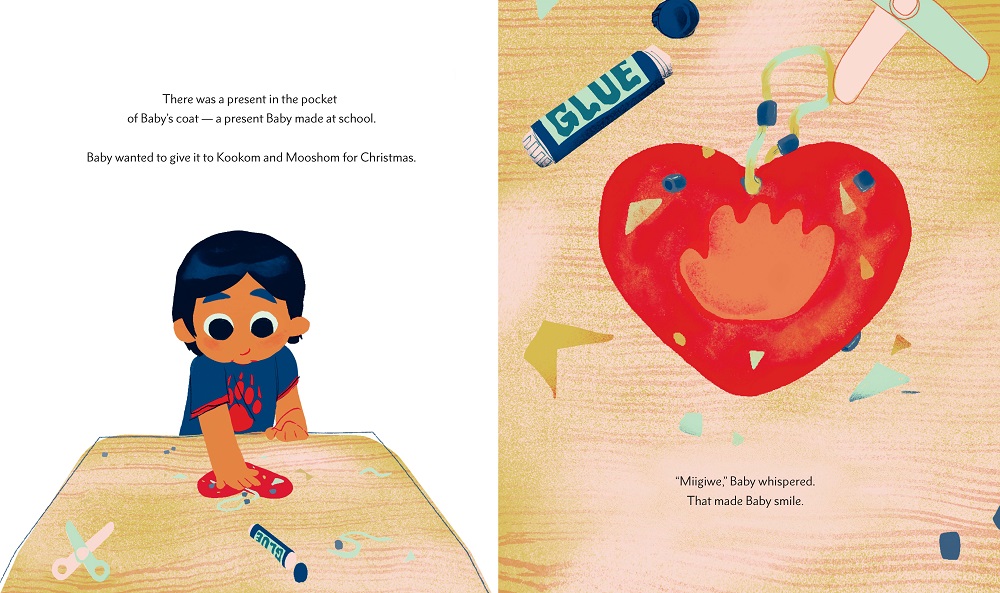

One thing the bear cub will not do is craft a gift for his grandparents, Kookom and Mooshom. The picture of this project is composed of carefully spaced elements, each one of which represents something important: creativity, love, simplicity, focus. Glue, scissors, a red paper heart, become a concrete expression of miigiwe, that Baby’s father has explained: “That means ‘giving away.’ And it’s good.”

The pictures by Erin Hill alternate outdoor panoramas, domestic interiors, and framed scenes of specific activities. A view of the family seated around a wood stove is set an angle and viewed from a slight elevation. Relatives embrace, but there is empty space between different sections of the picture. Kookom and Mooshom are thrilled to see their grandchild, but they listen carefully to his narration of the car trip. He has processed the truths his father communicated and his repeats them, with understanding, to the older generation. Do you have grandparents? Are you a grandparent? Do you remember your grandparents? You will never forget these scenes. The family goes outdoors, where they sing about the poetry of winter while playing drums. Whatever winter holiday you celebrate, An Anishinaabe Christmas will resonate as strongly as that chorus.