The Mona Lisa Vanishes: A Legendary Painter, a Shocking Heist, and the Birth of a Global Celebrity – written by Nicholas Day with art by Brett Helquist

Random House Studio, 2023

This is one of the most intelligent books for middle-grade readers that I have read recently. (It is equally appropriate for young adults and grownups.) When have you last found even a passing reference to the poet Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918) in a children’s book? He happens to be one of my favorite of the modernists, and he also played an indirect but important role in one of the most important art thefts in history. In fact, according to the mixed perspective of Cubism, where a painter can present an image from several different angles simultaneously, Apollinaire may have been front-and-center or off on the sidelines.

It’s far more likely that young readers have encountered Picasso, as well as Leonardo da Vinci, or at least a reproduction or a parody or an animated version of one of their most famous images. In The Mona Lisa Vanishes, Nicholas Day narrates the true story of an outrageous and puzzling crime. Da Vinci’s now most famous painting, but much less iconic at the time, was stolen from the Louvre in August of 1911. The crime remained unsolved until 1913, on the eve of the World War that would forever change everything. In parallel chapters, Day introduces Da Vinci himself, and describes the improbable circumstances under which he agreed to paint a young woman named Lisa Gherardini, the wife of Florentine merchant Francesco del Giocondo. No one, including the great Renaissance man himself, is romanticized in the book, but nor are they used as sources of easy humor. There is plenty of humor in the story, but it is all rooted in human gifts and foibles and in the sometimes random events that affect people’s lives.

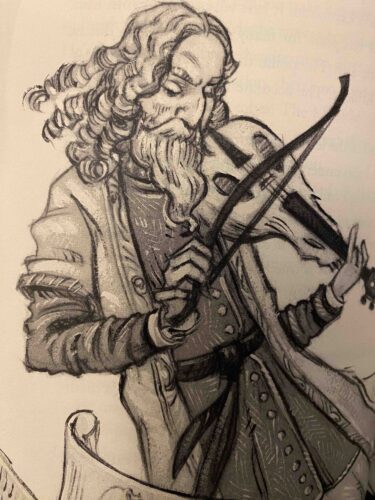

Not only does The Mona Lisa Vanishes tell a detective story, it also delivers a sophisticated yet accessible discussion of how fake news becomes more believable to the public than confusing facts. Day also illuminates Renaissance and modern art, changes in the nature of museums in over time, the economically marginal existence of artists, and the development of modern forensics. If the book sounds too ambitious, it is not. Readers, young and older, will not be able to put it down! Brett Helquist’s art depicts the main characters with gentle caricature. Chapters open with graphics in repeating patterns, while some sections of the story are preceded by black-and-white signage resembling the titles in silent movies.

It’s wonderful to contemplate how Day developed his idea, as well as the conviction that others would share his enthusiasm. The book is not a dystopian fantasy, a traditional biography of a well-known figure, or a straightforward investigation of one historical event. All of those subjects are wonderful possibilities for children’s books. This one is different. The concept may seem as enigmatic as the Mona Lisa’s smile, but the resulting work is a richly rewarding tour.