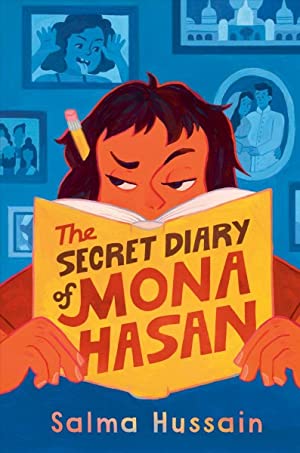

The Secret Diary of Mona Hasan – Salma Hussain

Tundra Books, 2022

Mona Hasan’s diary may be secret, but Salma Hussain’s novel should not be. This book, for middle-grade, young adult, and adult readers, surprised me on every page. When I started to read it, I expected another entry in the burgeoning field of novels about smart, imaginative girls struggling to find their place in a specific world. Sometimes they find the process more painful, while other heroines are optimistic and full of joy. They are from many different cultures, races, religions, and nationalities, and these differences differentiate them from one another, with more or less nuance. The Secret Diary of Mona Hasan begins with this template, but its originality and authenticity place it in a different category. It is a truly sophisticated work of literature that transcends its category.

Mona lives in Dubai during the 1991 Gulf War when the book begins. Her parents are originally from India and Pakistan. She has a younger sister, Tutoo, who is the cause of annoyance and also the object of her protective love. Mona attends a progressive school for Muslim students; its headmaster tries valiantly to promote equality for girls while not falling afoul of conservative religious standards. Mona’s mother is a frustrated feminist, and her kindhearted father goes to work in his financial job every day with paradoxical goals. Affluence is important to him, and yet, he is as unfulfilled as his wife: When Tutoo asks him why he is paid so much ‘to look at numbers all day,” replies, “No one would do this job otherwise.” Mona is caught in a vortex of hypocrisy. No wonder she confesses all her doubts, confusion, and anger to her diary. But she is also sharp, clever, bold, and ironic. She has a strong sense of class consciousness, an acute awareness of prejudice, and a conviction in her unique strengths.

Describing the plot of Hussain’s book doesn’t do it justice. Her language, sometimes mildly funny and lighthearted in other books of this genre, is explosively honest. Mona’s New Year’s resolutions include both “I will save a life from danger!” and “I will occasionally make my own lunches for school.” Aware of her record of academic excellence, Mona sometimes spells out words, as well as the concepts that drive her life: Her parents will hear “gushing accolades —–a-c-c-o-l-a-d-e-s” from the teachers who are fortunate to instruct her. When a word, such as “SLUTS,” is unfamiliar to her, she concludes that it must be misspelled. Will her pride and confidence lead to eventual disgrace? Actually, no. Mona will never suffer the consequences of uppity women and girls that she reads about in other books, such as Jane Eyre, even within a culture which bombards her with oppressive messages about her gender. In fact, she will take what she finds best about that culture and include it in the formation of her character. Her thought processes about both choosing to wear a head covering and later rejecting one are typical of Mona’s sense of empowerment, not thoughtless rebellion.

Mona refers to books several times, including to the popular series of British novels beginning with The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 ¾. Although she never mentions Judy Blume’s pathbreaking Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret , it is inevitable to compare Mona’s urgent appeals to Allah to Margaret’s poignant conversations with God, about everything from puberty to her confusions about her religious identity. Mona’s exasperation is more pointed than Margaret’s. When her father asks Mona to help her mother more in the kitchen, she naturally asks him why he cannot pitch in. His reaction to this idea as “ridiculous,” because he is a man leads Mona to ask Allah, “Isn’t it this world that You’ve created, that is completely ridiculous?”

Mona is not just an angry iconoclast. Her father is not a parody of male foolishness. Her mother is not hopelessly subjugated. No one in the novel conforms to facile stereotypes. Yes, at one point Mona concludes that both her parents are “feeble,” but she eventually comes to understand, and even appreciate, the forces that have made them who they are. When the family emigrates to Canada, Mona’s father suffers displacement and loss of status, and her mother continues to experience depression. They both adapt to change. Hasan’s characters develop within a believable range, while still challenging the reader’s expected trajectory for their lives. Watching the movie Aliens with her sister, Mona instructs Tutoo in the inspirational value of its tough female protagonist, “I pointed at the screen. ‘Look closely. We don’t have to play nice. Look at where anger can take us.’” Anger, courage, self-awareness, and love all stand out in this remarkable book.