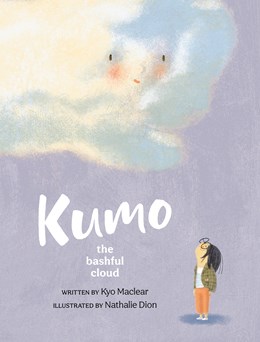

Kumo the Bashful Cloud – written by Kyo Maclear, illustrated by Nathalie Dion

Tundra Books, 2022

Children sometimes personify clouds, and so do adults. While the actual scientific facts about their existence is also enthralling, spinning stories about their evanescent shapes is an important pastime. Kumo is bashful, insecure, but also socially enough inclined to welcome the friendship of Cumulus and Cirrus.

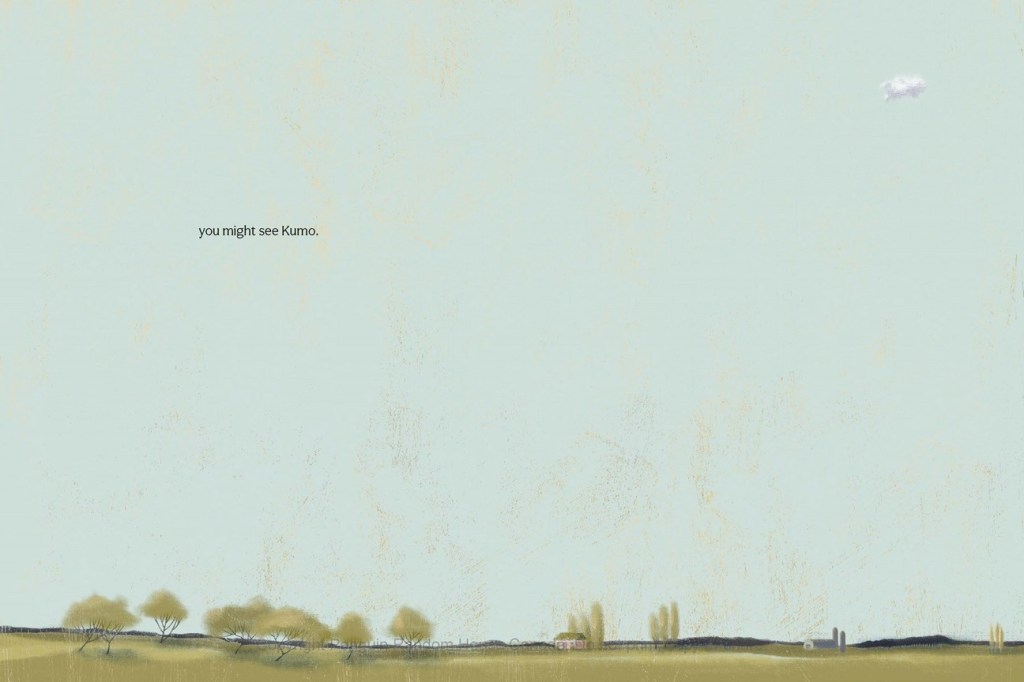

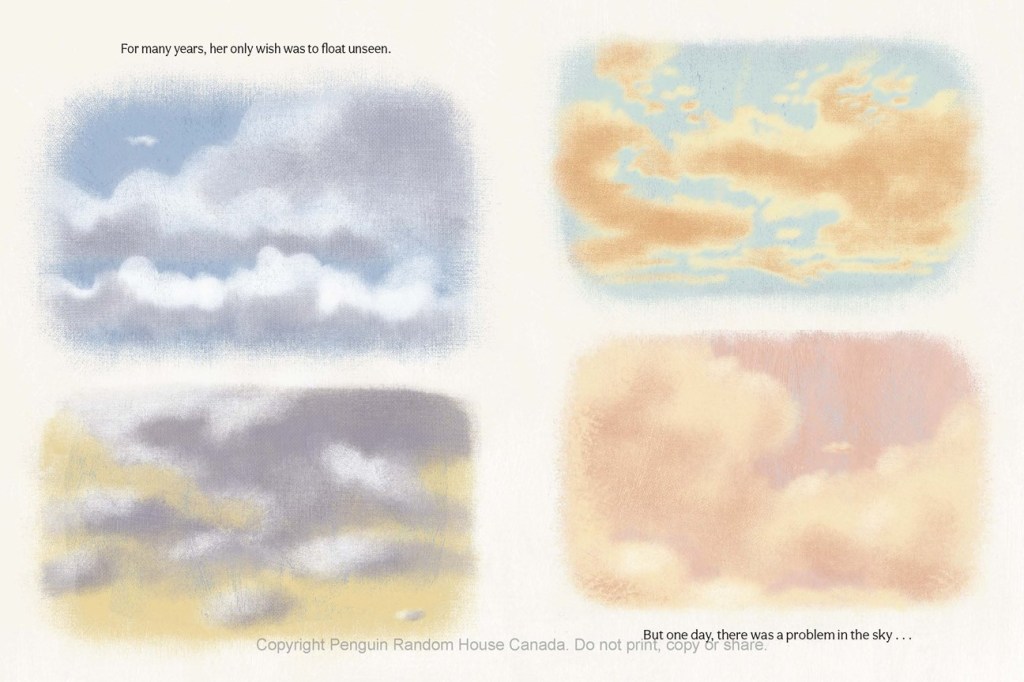

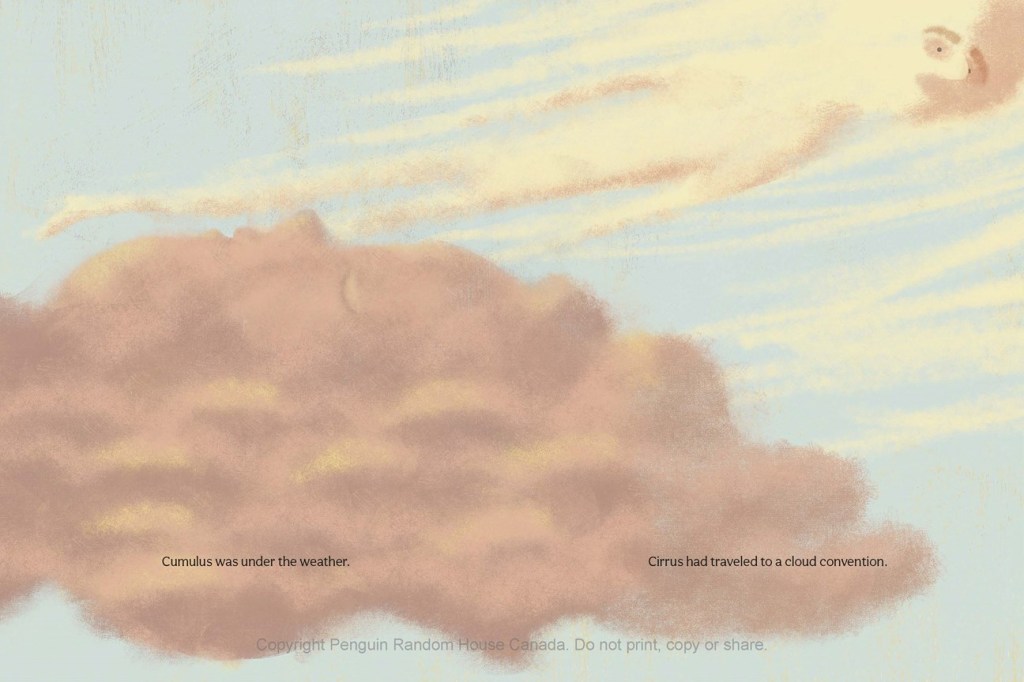

When the book opens, Kumo is so pale as to be almost invisible. As Kyo Maclear narrates (I’ve reviewed her other works here and here and here and here and here), “for many years, her only wish was to float unseen.” Yet circumstances change and she adapts, if, at first, reluctantly. “Her mind was heavy with doubt” may seem an intense statement of consciousness to a child, but it makes sense. She is frightened, then trapped in a tree. A friendly kite, not a cloud by cloud-adjacent, helps her out. So does the wind, and a lake, fields, and “singing glaciers.” The natural world is her ally. But When Cumulus feels “under the weather” and Cirrus departs for a cloud convention, she is worried.

Nathalie Dion’s pastel images with touches of brighter color perfectly match the poetry of the text. Eventually, Kumo begins to interact more with the human world, helping a man to plant petunias, and even enjoying an urban scene full of lively families. One child holds a red balloon, while another, with oversized black glasses and dark hair, wears matching red pants. That child is revealed to be somewhat like Kumo. With his head in the proverbial clouds, he loves to dream. Soon he transforms Kumo into a bunny, a car, and a flying horse.

With the boy’s help, Kumo ascends to “the top of the world,” and even reaches out to new friends. With the lovely Japanese names of Fuwa-chan, Miruku, and Mochi, helpfully explained in a short glossary, they support one another, both literally and figuratively. Being alone and having friends, both meteorological and human, both turn out to be within Kumo’s flexible reach. Kumo the Bashful Cloud reveals wisdom with a light touch.