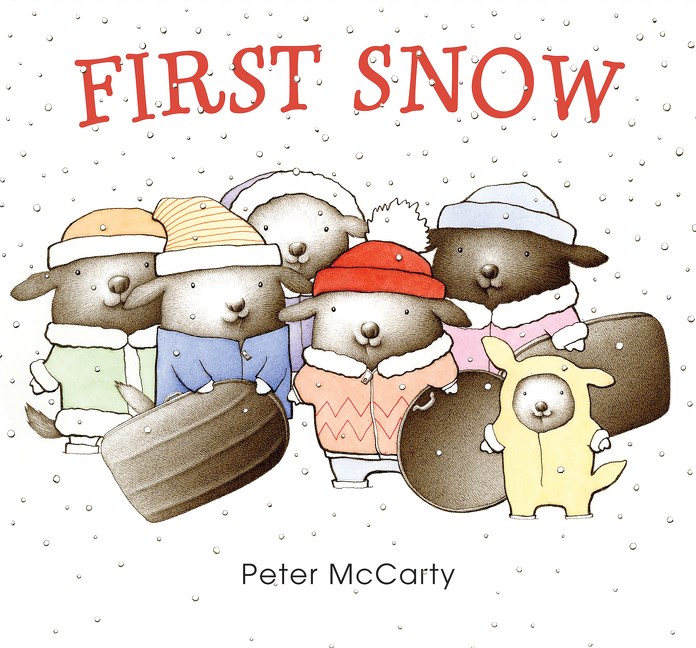

First Snow – written and illustrated by Peter McCarty

Balzer + Bray, 2015

It may not be the first snow, but, due to climate change, it certainly feels like it in many parts of the country. In Peter McCarty’s classic, First Snow, a group of different stylized animals responds with excitement to the event, although one skeptic objects to the cold and the unfamiliarity. Pedro, the “special visitor” who announces his reservations is both the voice of reason and kind of annoying. After all, in order for it to snow it has to be cold, but if he can’t adapt he will miss the beautifully illustrated fun.

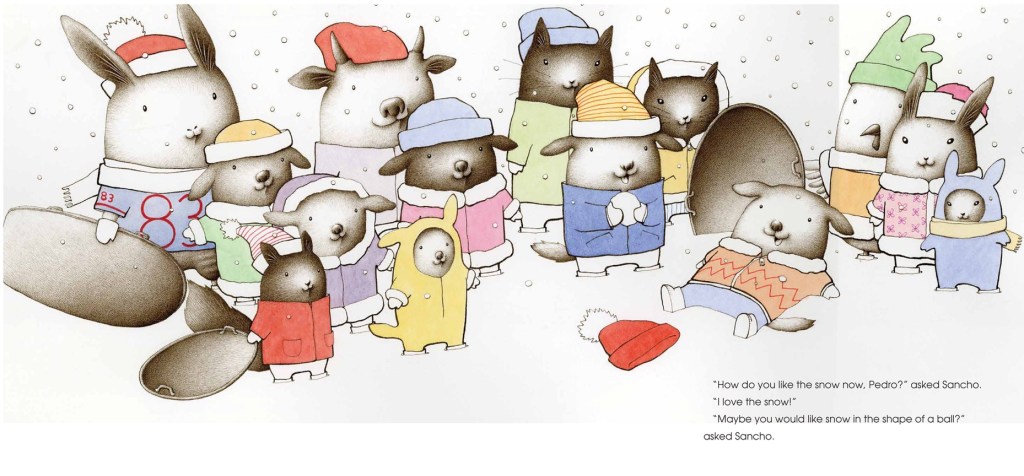

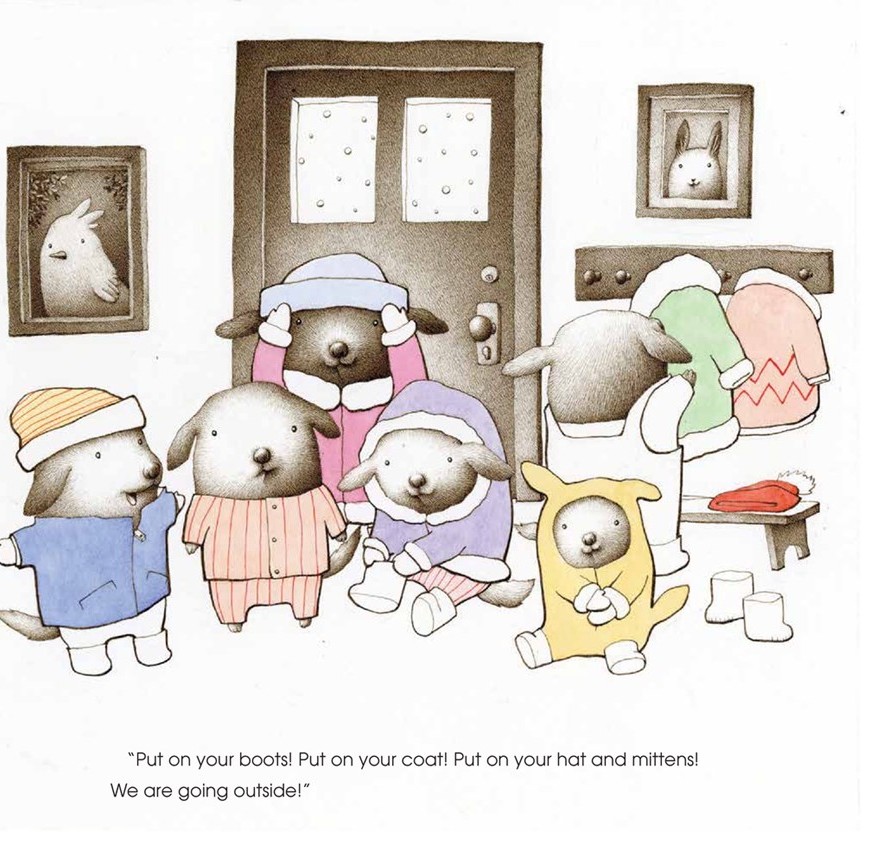

There is a mysterious tone to the story, or perhaps it just reflects the perceptions of children. Pedro has traveled unaccompanied to visit his cousins. They appear to be dogs, drawn in simple, rectangular forms. The mother has pink bows in her hair. The children, with the resonant names of Sancho, Bella, Lola, Ava, and Maria, welcome him. (Later, Bridget, Chloe, and Henry will appear.) At bedtime, Sancho points out the snow has begun to fall. His bedroom has pictures on the walls of dogs bicycling and playing baseball. There is a toy dinosaur on the dresser. Pedro expresses his fears.

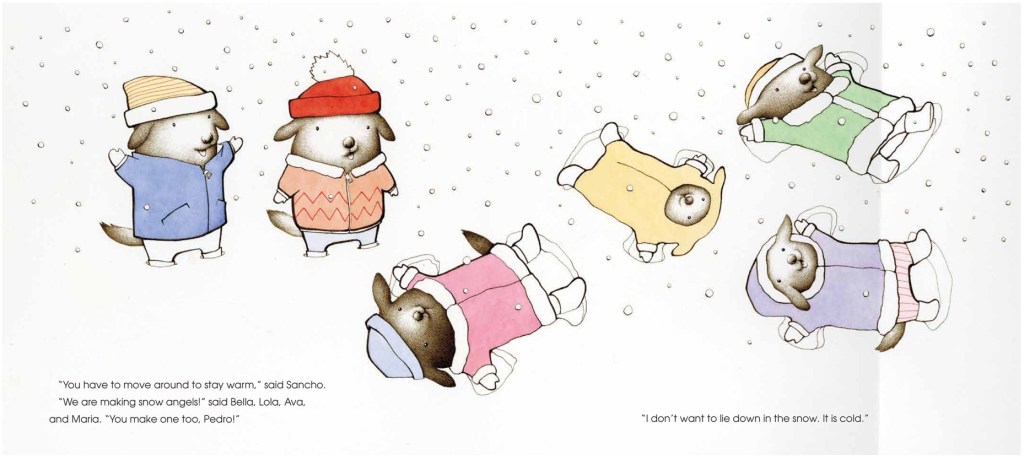

The scene then moves from domestic calm to exuberance, as everyone but Pedro gets ready to emerge from the house and play. They dress in puffy snow gear and make snow angels. Sancho helpfully points out that moving around is key to staying warm, but Pedro repeats his reservations. Readers may identify with his hesitancy, or feel frustrated by his obstinance. Those different possible reactions frame the entire story.

Other neighborhood children join in. There are birds, cats, and cows, united in their happiness. Abby describes the sensation of feeling snowflakes on your tongue, to which Pedro predictably answers, “It tastes cold.” Eventually, having voiced all possible objections, he begins to participate in sledding. There is plenty of white space separating the pictures, giving a sense of movement. When Pedro decides, or admits, to loving the snow any sense of surprise may be either muted, or genuinely impressed by the change in the visitor’s attitude. Any child, or adult, who welcomes snow, even while acknowledging its potential nuisances, will appreciate this book.