Late Today – written by Jungyoon Huh, illustrated by Myungae Lee, translated from the Korean by Aerin Park

Eerdmans Books for Young Readers, 2025

The opening endpapers of Late Today show an overcast sky. The following two pages feature the consequence, a bridge accompanied by the warning that “Morning rush hour traffic is congested all over Seoul,” with the report’s words alternating in word of the report alternating in level relative to the image. The title page shows an adorable kitten with golden brown eyes that match the lid of the carton which has become her bed. Readers join the traffic jam and the rescue mission.

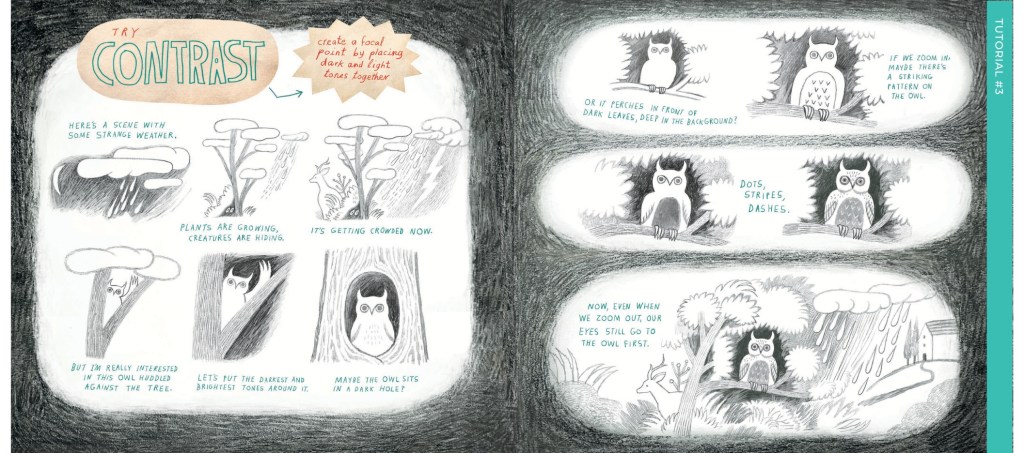

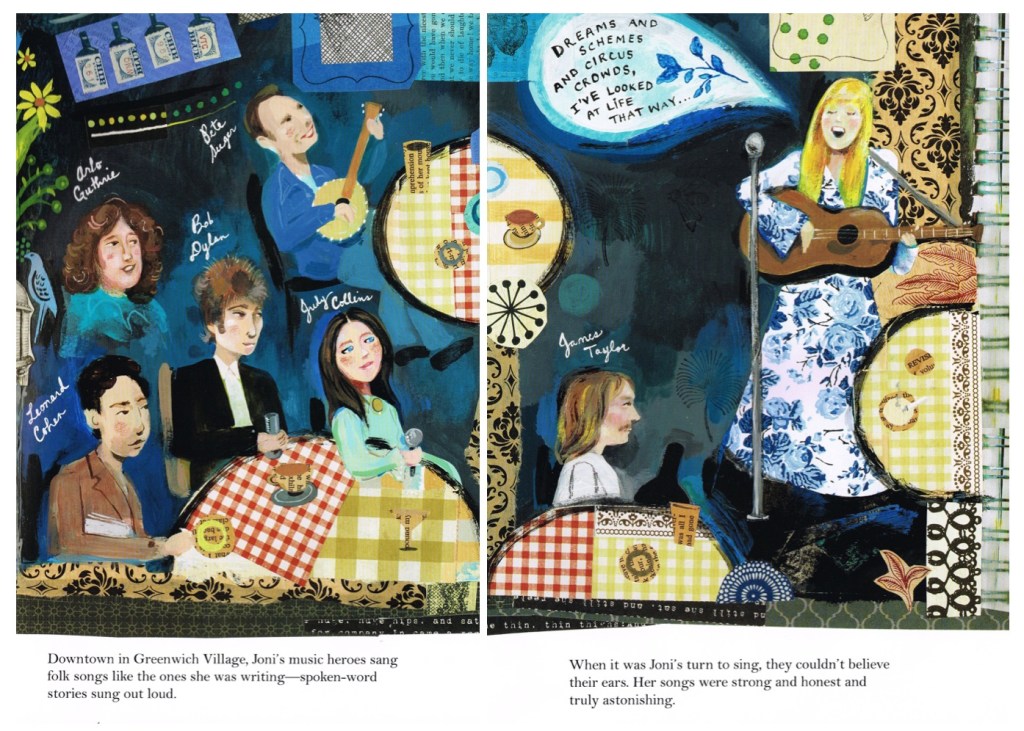

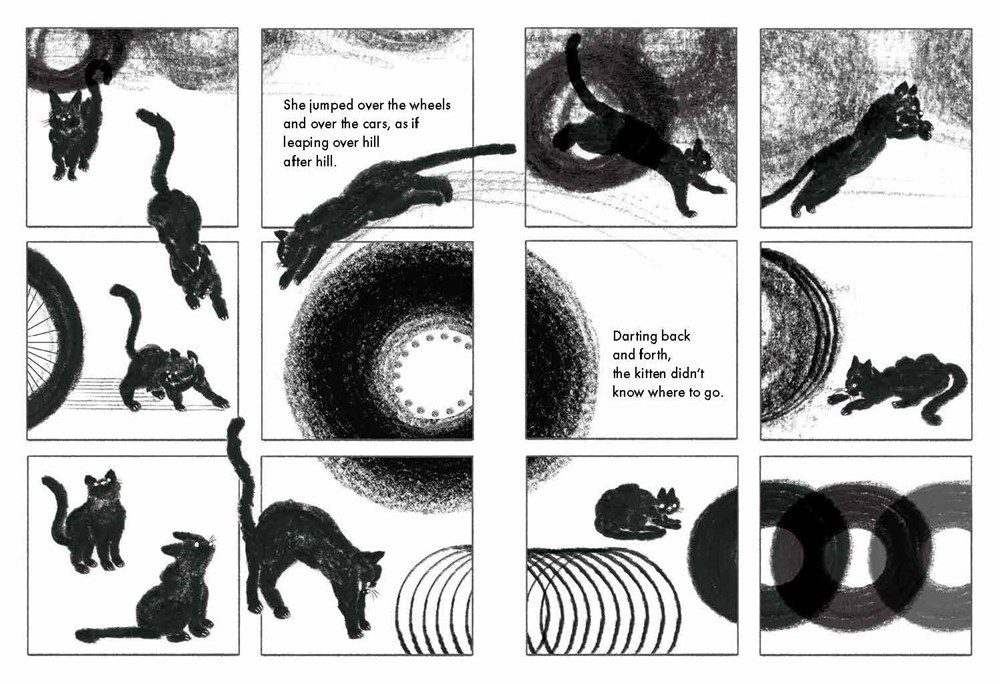

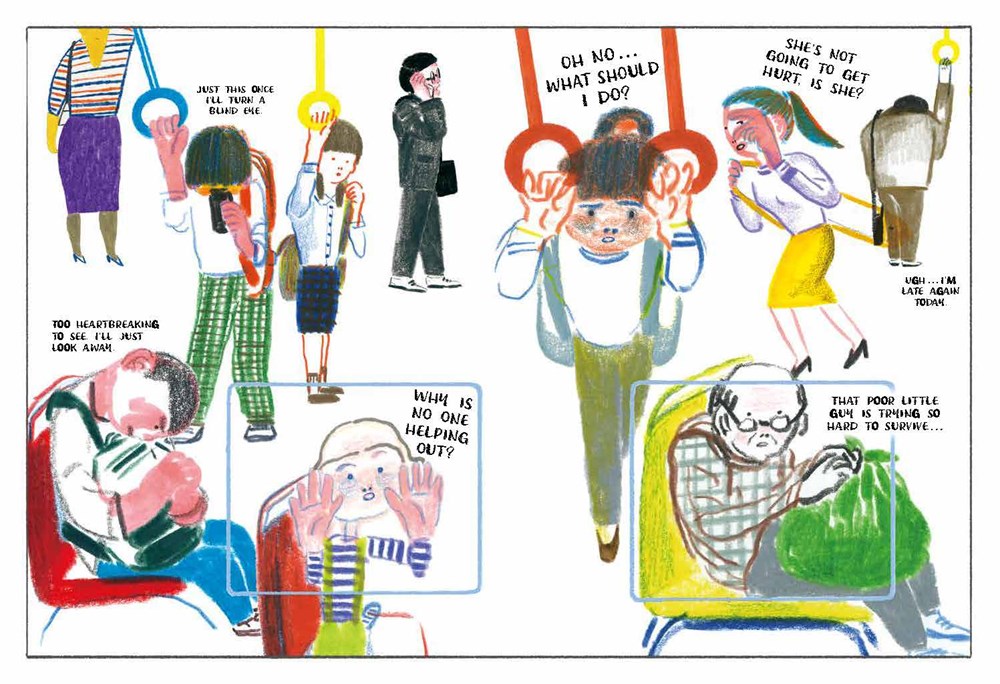

Jungyoon Huh’s minimalist text (ably translated by Aerin Park) conveys just exactly the amount of information needed. Myungae Lee’s illustrations, rendered in colored pencils and oil pastels, combine black and white scenes, graphic novel panels, and earth and jewel tones against white background. They are beautiful in their simplicity, but also convey motion, sense impressions, and the imminent threat of losing a kitten on a traffic-clogged bridge. The black font ranges in size, with some pages reminding me of the lettering used in Margaret Wise Brown and Leonard Weisgard’s The Noisy Book, and sequels. (The Winter Noisy Book is illustrated by Charles G. Shaw.)

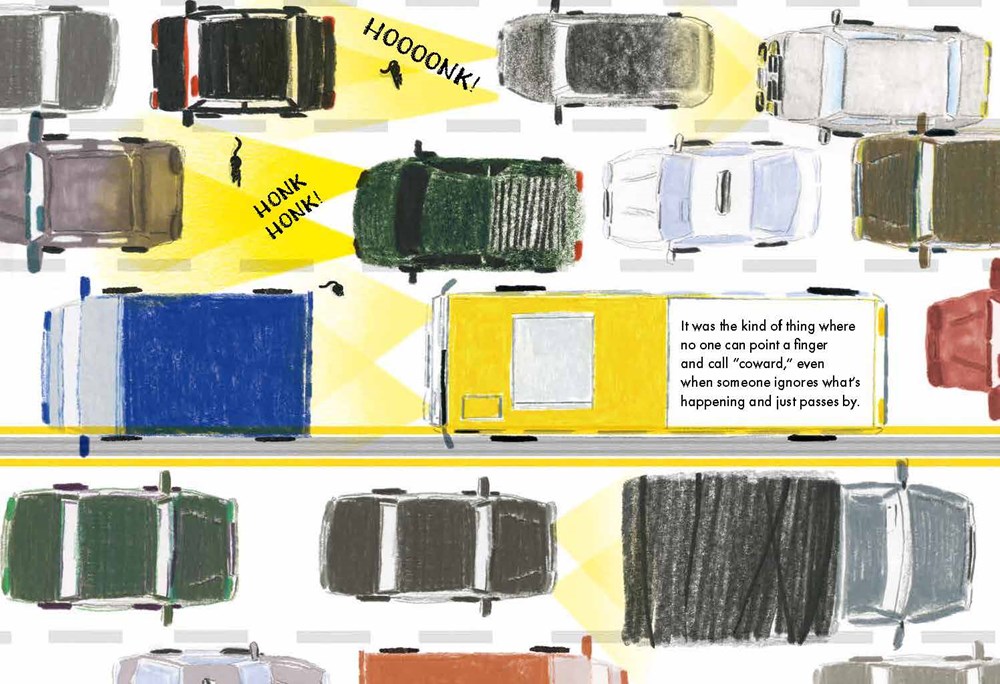

Public transportation passengers, each in isolation, express their own thoughts about the danger, and their appropriate response to the kitten’s plight. Parents and caregivers sharing the book with children will want to discuss all the implications of these natural, but possibly inadequate, emotions: “Why is no one helping out,” “Too heartbreaking to see. I’ll just look away,” and Oh no…what should I do?” One incredible two-page spread is a bird’s eye view of the vehicles, each one inadvertently threatening the tiny kitten weaving between them. The text is enclosed in a rectangle similar in size to the vehicles themselves, the words visualizing the ominous situation.

Cinematic techniques dedicate to full pages to a darkening storm, and another two to pelting raindrops. Readers pause and take a deep breath. Then, a driver rescues the kitten, his or her hands cradling the animal in a gesture of human kindness. Someone has intervened at exactly the right moment. The cars and buses move. Everyone is relieved. Being late is sometimes exactly right.