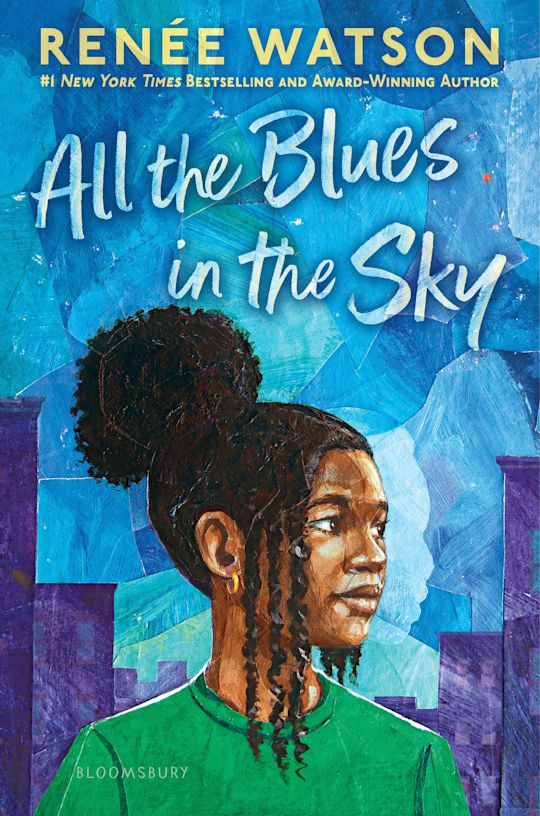

All the Blues in the Sky – by Renée Watson

Bloomsbury Children’s Books, 2024

Sage is a thirteen-year-old girl whose best friend is killed by a reckless driver. This terrible event happens on Sage’s birthday. The terms “losing” someone, or “passing away,” would be completely inadequate to describe the shock, numbness, and internalized rage that follow the accident. Renée Watson’s verse novel gives Sage a voice in each chapter, narrated from the unaffected perspective of a person confronting emotions that would level a strong adult. With the same sensitivity to the process of growing up shown in her other works (which I have reviewed here and here and here), Watson creates characters who are vulnerable, but also strong.

In All the Blues in the Sky the experiences that test Sage are not the ordinary, but still difficult ones, of every adolescence, although those experiences, such as having divorced parents, are the framework for her growth. Her parents are supportive, as is Aunt Ini, her surrogate grandmother. She even has the benefit of a grief counseling group facilitated by Ms. Carver, who is nothing if not patient and professional. Mr. Dixon, Sage’s dedicated math teacher, offers slightly irritating, but totally sincere, life lessons: “Understanding angle relationships in math will help you understand your personal, real-life relationships…There are people –like transversal lines – that cross paths with you, only for a moment.”

There are other people in her life who are grieving. Zay’s grandmother has died, and she admits relief at the end of her suffering. DD’s brother was killed by the police. Ebony’s father had a heart attack. Sage is forced to constantly evaluate which types of death are hardest for survivors. No one has been able to answer this question. Her friend’s death was abrupt and senseless. Sage never had a chance to say good-bye. Other survivors had to helplessly watch a long period of illness preceding a death. Another troubling part of Sage’s role, which is only implicit in the novel, is her specific relationship to the person who died. She is not a sister, mother, or child, but a friend. When a relationship is not formally recognized, the most profound sadness can seem somehow less important, although her friend’s family certainly honors Sage’s role in their loved one’s life.

For almost the entire book, Sage’s friend remains unnamed. There could be many narrative, and psychological, reasons for this choice. Articulating her name is too difficult, too final. Nameless, she is both a real person and a tangible symbol for anyone who has grieved. Words cannot capture the friend’s unique qualities, although Sage gives many examples of their closeness, and even of the tensions that leave her with unresolved guilt. But specific, mundane, questions are more important than generalities: “What will her parents do with the posters on the wall?” Sage asks, “What will they do with her jean and T-shirts and sweaters/ and sneakers and sandals and socks and leggings and bracelets/ and earrings…”

Sage grieves, but she also falls in love, and begins to fulfill her dream of learning to fly. More losses are in store, and Watson never minimizes their depth with platitudes. “If I live long enough to be an adult/and if I have children when I am an adult/I will tell them as much as I can about all the loss…” The phrase. “If I live long enough” from a girl of thirteen is terrible, but Sage’s resolve to tell her children the truth is something of a triumph.