The Complete Adventures of Curious George: 75th Anniversary Edition – H.A. and Margret Rey, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016

The ABC of It: Why Children’s Books Matter – Leonard S. Marcus, Foreword by Lisa Von Drasek, Kerlan Collection at the University of Minnesota, 2019

The Journey That Saved Curious George: The True Wartime Escape of Margret and H.A. Rey – Louise Borden and Allan Drummond, HMH Books for Young Readers, 2005

The Journey That Saved Curious George Young Readers Edition: The True Wartime Escape of Margret and H.A. Rey – Louise Borden and Allan Drummond, HMH Books for Young Readers, 2016

Monkey Business: The Adventures of Curious George’s Creators – film directed by Ema Ryan Yamazaki, The Orchard Studio, 2017

In 1940, a German Jewish couple fled occupied France in danger of their lives. Traveling first to Brazil and then to the United States, they brought with them the manuscript for what would become the first in a series of one of the most enduring and popular children’s books, Curious George. Author H.A. Rey and his wife, illustrator Margret Rey, brought to life the little risk-taking monkey who was frequently rescued from near disaster by his patient and benevolent friend, the man with the yellow hat. Unlike a toddler, George cannot speak. Like a toddler, he is often misunderstood. Impulsive, highly physical, affectionate, and essentially kind, George became a character with whom children could easily identify. He represents both their best and their most difficult characteristics, but his adventures are always resolved without serious harm to anyone. Most significantly, George represents parental compassion and unconditional acceptance. Note his introduction to the world: “He was a good little monkey/and always very curious.” That “and,” not “but,” promises that even George’s most problematic behaviors are routed in a healthy embrace of the world.

There is currently an acclaimed exhibit at the University of Minnesota’s renowned Kerlan Collection of children’s literature. (The amazing story of Dr. Irvin Kerlan, and how he came to create his collection and leave it to the University of Minnesota, would itself be worth of its own blog post.) The exhibit is co-curated by Lisa Von Drasek, Curator of the Children’s Literature Research Collections that includes the Kerlan Collection, and Leonard Marcus. The exhibit is a revised version of the one originally curated at the New York Public Library from 2013-2014 by Marcus, a well-known and distinguished scholar of children’s literature. (I saw the original exhibit; I thought it was one of the most comprehensive and exciting approaches to children’s literature that I could imagine.)

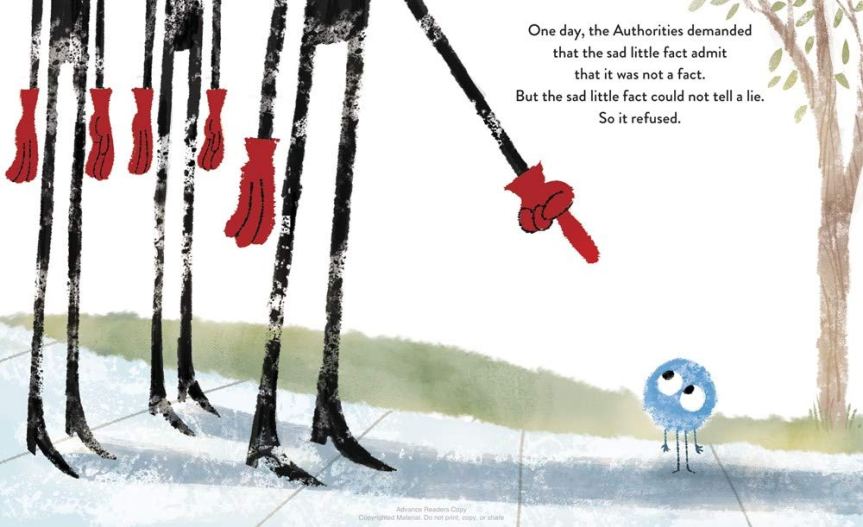

Not surprisingly, the Minnesota exhibit has received some criticism, which is healthy. Viewers should always feel free to analyze and respond to perceived shortcomings in a public exhibition, even more so when the subject is as central to our daily lives as the role of books in the daily lives of our children. In the years since the New York exhibit opened, parents, educators, and scholars have expressed concerns about the need for diversity in books for children, with a greater confidence that their ideas would be listened to seriously than had been the case in the past. One of the issues raised has been the difference between celebration and documentation. If a book from an earlier era reflected the racism or sexism of that time, how should be approach it today? In my opinion, the worst response is censorship. No, censorship is not strictly the government-controlled decision to legally outlaw certain books. We don’t have that in the United States, although we can no longer take for granted that it does not loom on the horizon. Censorship is also commonly understood to mean deliberately making access to books or other works difficult, discouraging or threatening publishers, libraries, or bookstores, and impugning the motives of any author who fails to agree with the critics’ perspectives or cede to their demands. Wrapping a book in yellow caution tape in a public exhibition, as opposed to criticizing it and publicizing alternative perspectives, is wrong, and reminiscent of terrible times in history when books were physically destroyed. (Here is a link to a post at the University of Minnesota’s Library blog that had originally depicted this act; that since has been removed; my description comes from memory: https://www.continuum.umn.edu/2019/04/the-abc-of-it-things-to-think-about-caddie-woodlawn/.)

Back to Curious George. The section in the exhibit on George now links him to other depictions of monkeys in literature, some of which are examples of crude and ugly racism, and makes the claim that therefore all depictions of monkeys in children’s literature, including George, are inherently racist.

Yes, the man with the yellow hat does “rescue” him from Africa. The Reys were European, a continent with virtually no native species of monkey. Originally, he is also put in a zoo, where he is very happy, but in subsequent books in the series he is living comfortably in a human home and enjoying a great deal of freedom. Oh, and the man with the yellow hat smokes like a chimney. I have posted on Curious George numerous times (here and here and here), including on this problematic habit.

Viewers, and readers, can reach their own conclusion about the accuracy or justice of this comparison. Look at George’s grief when he realizes, as toddlers inevitably do, that his actions have consequences, as when he inadvertently lets all the bunnies out of their hutch in Curious George Flies a Kite (“George sat down. He had been a bad little monkey. Why was he so curious? Why did he let the bunny go?”), or when he just has to taste the puzzle piece and winds up in the hospital, where he cheers up the other kids by crashing the food cart. If only life were like this! In the Curious George books, the daily hazards of life are never catastrophic and bad decisions never have permanent consequences. The Reys offered readers a safe introduction to negotiating the real world, one where adults will always care for you. Critics intent on placing George in a historical context of racism might also wish to learn more about the harrowing circumstances in which the Reys, themselves the victims of racism of the most murderous sort, managed to create this reassuring and endearing character for all children to enjoy.