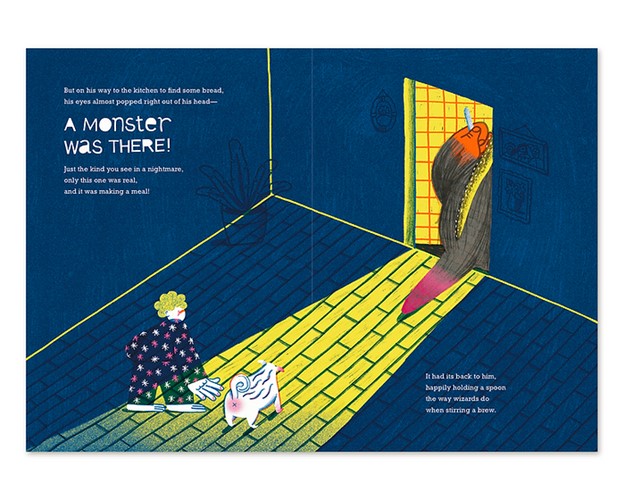

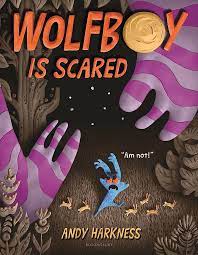

Wolfboy is Scared – written and illustrated by Andy Harkness

Bloomsbury Children’s Books, 2023

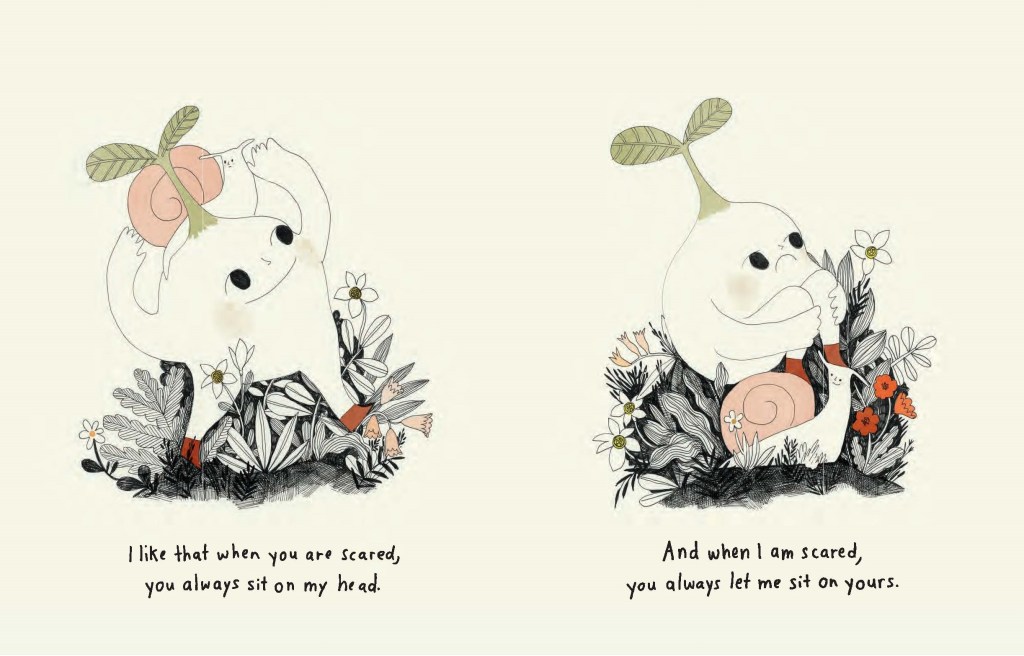

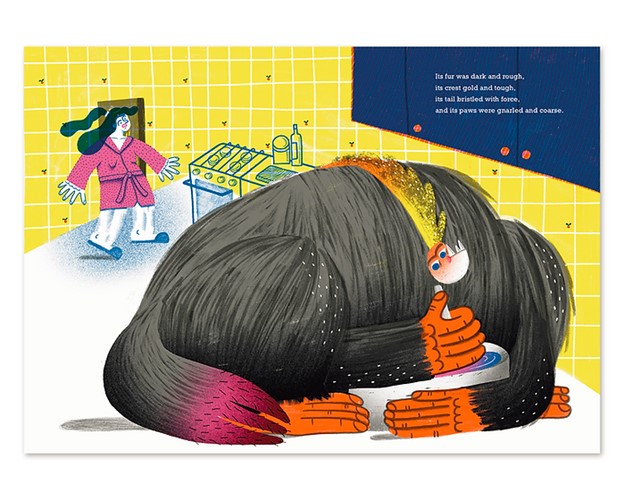

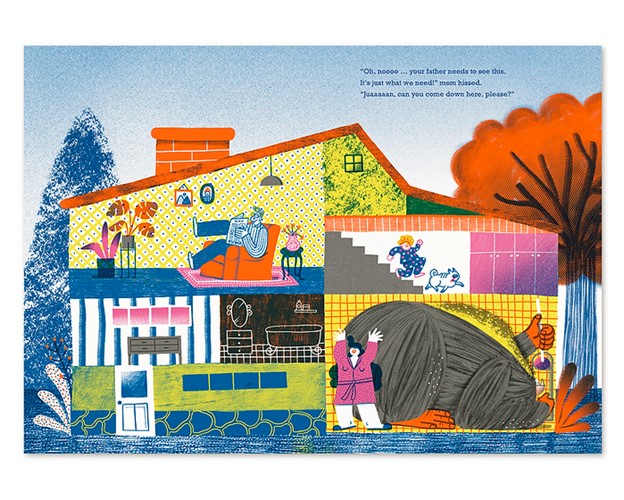

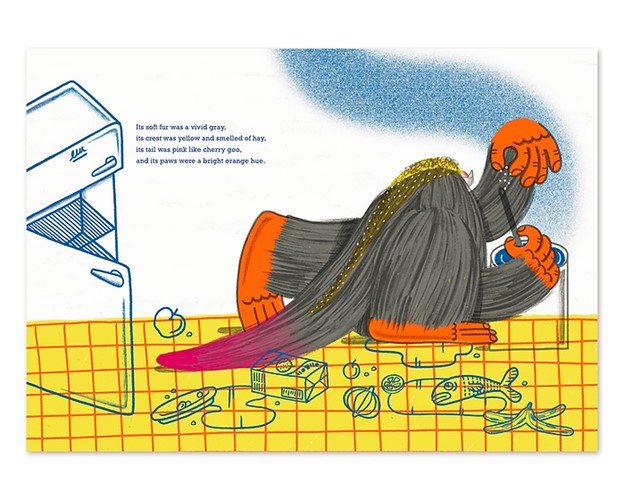

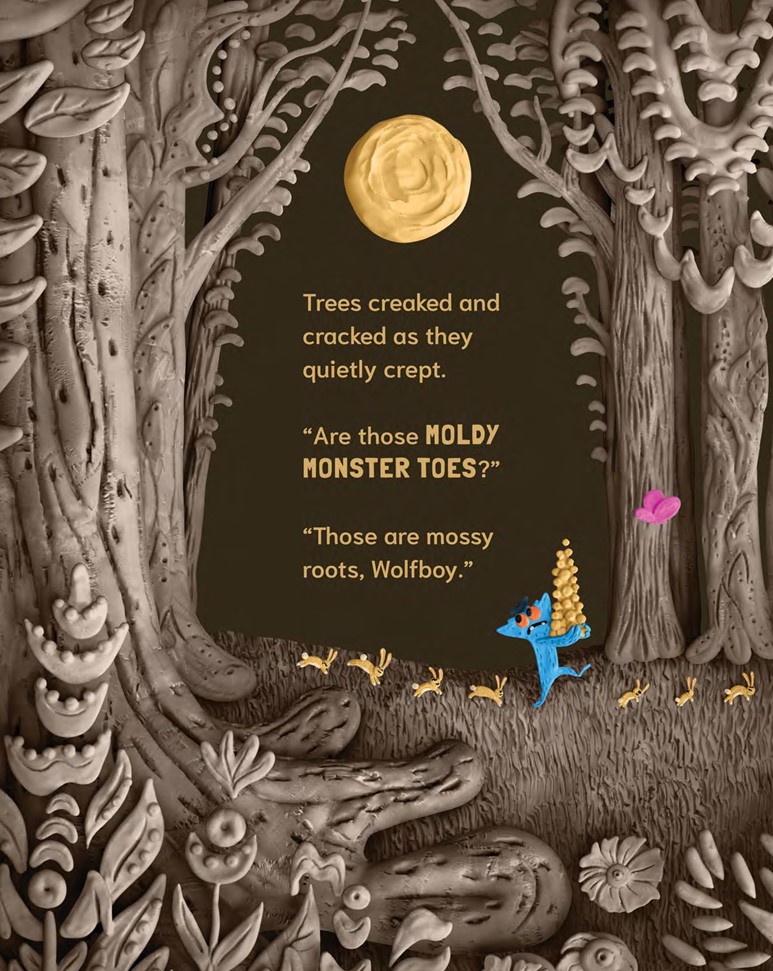

Wolfboy, the molded clay monster who befriends rabbits rather than eating them, has returned. The woods are still full of moonberries and the moon itself looms in the sky, its surface covered by swirls of thick yellow instead of craters. In the first book, Wolfboy was transformed from hangry to happy. Now he has reliable friends, but he is subject to fears. Who wouldn’t be, walking through a forest of ghostly trees, whose roots could well be the toes of a dangerous and aggressive monster? The tension builds, but never to an overwhelming point, and finally resolves in a calm bedtime.

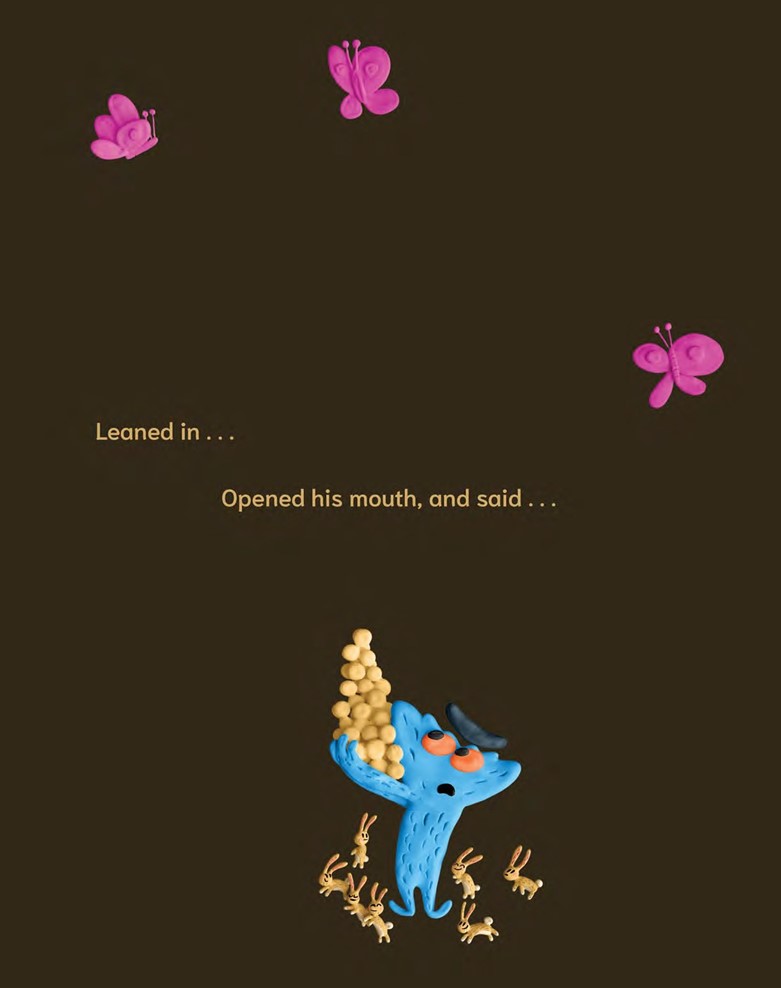

Andy Harkness includes a brief explanation of his artwork preceding the story. His creative process involves virtual reality, photographed clay, and the careful use of lighting, but the result is difficult to reduce to that information. Wolfboy looks both real and fantastic and the same time, and so does his adversary, Grumble Monster. Harkness’s use of color is key, from Wolfboy’s bright blue fur to his orange and black eyes moving at expressive angles. Magenta butterflies are guiding lights in the gray and taupe woods, while bunnies look like carefully shaped cookie dough. The pictures’ tactile quality is immersive, and appealing to young readers.

The visual element predominates in bringing Wolfboy to life, but his words complement the unfolding of his personality. Children love repetition, and they also like to ask questions. Wolfboy’s repeated requests for reassurance from the bunnies come in this form. “Are these creepy monster claws?” and “Are those glowing monster eyes” are not meant to elicit information, but to hear the answer, “no,” followed by an alternative. When he offers food to assuage his possible enemy, there is deliberate ambiguity. Is he cleverly manipulating Grumble Monster by identifying with his feelings? (“I know how you feel”) Maybe he is just following his instincts, holding up a pyramid of moonberries that would make any monster content, at least for the moment.

In the last picture, Wolfboy is asleep, next to a plate of cookies and a glass of milk. A static calm replaces the ominous atmosphere. Outside the window, a single butterfly appears against a light blue sky, with no evidence of fear-inducing creatures in sight. Even Wolfboy needs a rest.