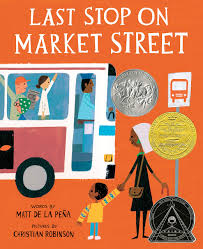

Last Stop on Market Street – written by Matt de la Peña, illustrated by Christian Robinson

G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2015

As we celebrate Martin Luther King’s Birthday this year, I thought of a wonderful award-winning picture book that affirms Dr. King’s revolutionary leadership and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. While racial justice was at the core of the March, so was Dr. King’s vision of policies which would enable people of color, and all Americans, to attain the type of freedom which only economic security can bring. Along with those policies and programs, empathy and solidarity are also at the center of change, a truth beautifully present in Matt de la Peña and Christian Robinson’s picture book, Last Stop on Market Street.

Kids sometimes complain; abstract insistence on the principal of gratitude are ineffective. C.J. is a young boy who is aware of all he is missing, watching others with material goods as well as the freedom to pursue their own version of fun, instead of accompanying their grandmother after church to a place where others need their help. Even though “The outside air smelled like freedom,” C.J. is forced, from his perspective, to walk in the rain to the bus stop and then to board the bus, where he “stared out the window feeling sorry for himself”. There are no lectures from his grandmother. Instead, factual observations and poetic metaphors meet in her patient but assertive answers to C.J.

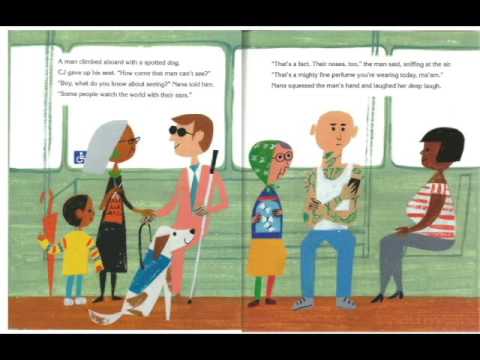

His friends, she points out, are deprived of an opportunity; the bus is full of unforgettable people: “I feel sorry for those boys…They’ll never get a chance to meet Bobo or the Sunglass Man.” When her grandson demands answers, she is ready: “’How come that man can’t see?’” “Boy, what do you know about seeing,’ Nana told him. ‘Some people watch the world with their ears.’”

Robinson’s pictures are use simple shapes and minimal definition to portray the depth of human experience. Two lines on a face from nose to chin denote age, a boy looking up at two standing commuters conveys a child’s sense of smallness. The artist’s evocation of compassion shines from every image in the book. When C.J. and Nana arrive at a community center where guests are served food, his frustration disappears; condescension was never even on the table. There is not division, as C.J. views them, between helpers and people who need help. There is also no irritating righteousness from Nana: “’When he spotted their familiar faces in the window, he said, ‘I’m glad we came.’ He thought his Nana might laugh her deep laugh, but she didn’t” Children can tell patronizing or inauthentic adults from those like Nana, who respect them. Last Stop on Market Street speaks to them, and to their caregivers, with compassion and truth.