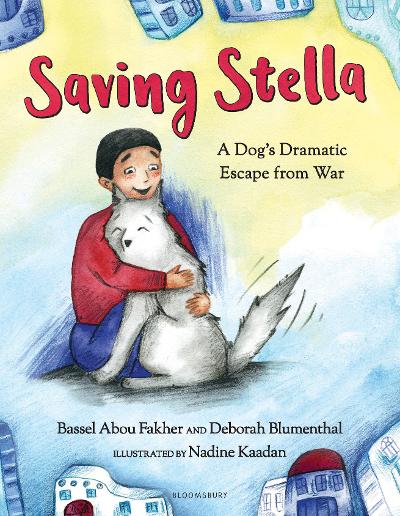

Saving Stella: A Dog’s Dramatic Escape from War – written by Bassel Abou Fakher and Deborah Blumenthal, illustrated by Nadine Kaadan

Bloomsbury Children’s Books, 2020

Authors presenting tragic events in picture books for young children always face a challenge. They need to filter the most disturbing aspects of the book’s subject, while respecting young readers’ ability to learn about the darkest of situations. In Saving Stella, authors Bassel Abou Fakher and Deborah Blumenthal (author of a biography of Judith Lieber) and illustrator Nadine Kaadan, succeed in telling the story of a boy and his dog’s escape from the chaos of Syria by focusing on truthful information within a reassuring and artistically beautiful framework. Stella, the big, affectionate dog who is part of Bassel’s life, is not a mere symbol for human suffering, but nor is his peril equated with that of the thousands of people caught in the senseless violence of his homeland. This is a book about one boy and the pet who serves as an emotional anchor, but also about the cruel injustice confronting refugees all over the world. Sharing the book with children offers the opportunity to discuss this painful reality, but also to highlight the ways in which at least some individuals may find a haven, and the freedom which had been denied them.

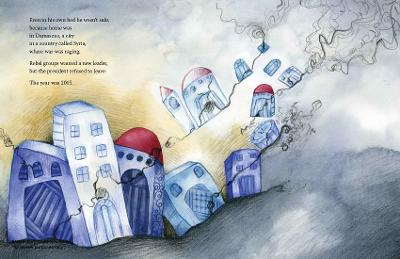

Both the pictures and text strike an appropriate balance, using understated but clear words and bold images to convey young Bassel’s fears:

The fighting grew wider.

Gunfire and explosives ripped through the city.

Bombs toppled buildings like wooden blocks.

Parents were afraid to go out to buy food.

Children were afraid to go to school.

The concise series of facts are striking. Some of children’s worst fears involve the inability of their parents to protect them. The daily expectation of attending school is destroyed. Kaadan avoids graphic images of death, instead creating pictures that artfully combine metaphor and reality; the buildings do indeed reflect the wooden blocks of children’s play, at the same time that they depict Syrian architecture.

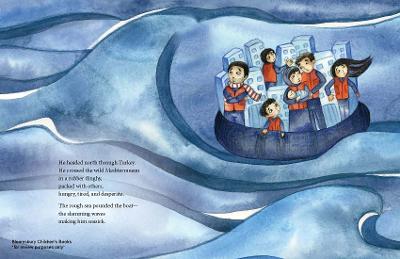

Bassel’s experience is one that children will easily understand; he is terrified, but still intent upon “pretending it was okay.” He knows that emigration is his only choice, but that this will entail the sorrow of leaving family and friends, as well as abandoning his dog, Stella. The image of Bassel crossing the Mediterranean, along with other refugees, in a fragile rubber dinghy is dreamlike and powerful. Appearing almost static although dossed by waves, four of the emigrants look out towards the sea, while a couple holding a baby focus on one another. In the small vessel, the buildings of Damascus form the background, reminding both the characters and readers that the city which they abandon will still be part of their internalized past. (Kyo Maclear and Rashin Kheiriyeh made a similar point in Story Boat.)

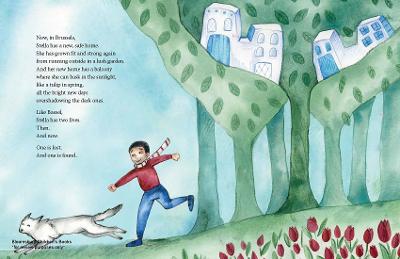

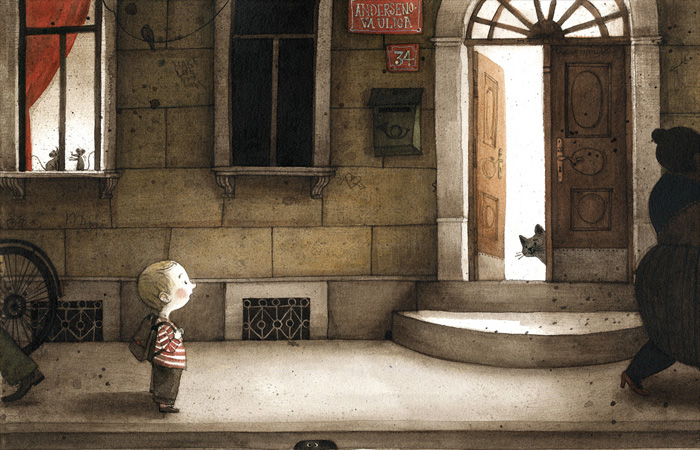

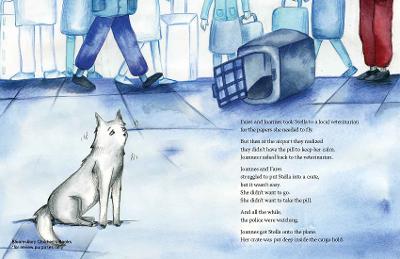

From his safety in Brussels, Bassel develops a plan to save Stella, giving children some sense of comfort in the power of helpers to effect change. The scene in the airport shows the reluctant dog watching, from his perspective, as human legs both wait and walk through the terminal. Stella is so fearful that she resists and determined people need to take control. After Bassel and Stella are reunited, the authors emphasize their opportunity to start a new life, renewed “like a tulip in spring.” Detailed notes from author and illustrator, as well as background information and further sources follow the text, offering a useful context. Throughout this subtle and affecting picture book, a consistent message emerges. People can escape suffering and compensate for their loss by remembering the past and living their present lives: “One is lost,/And one is found.”