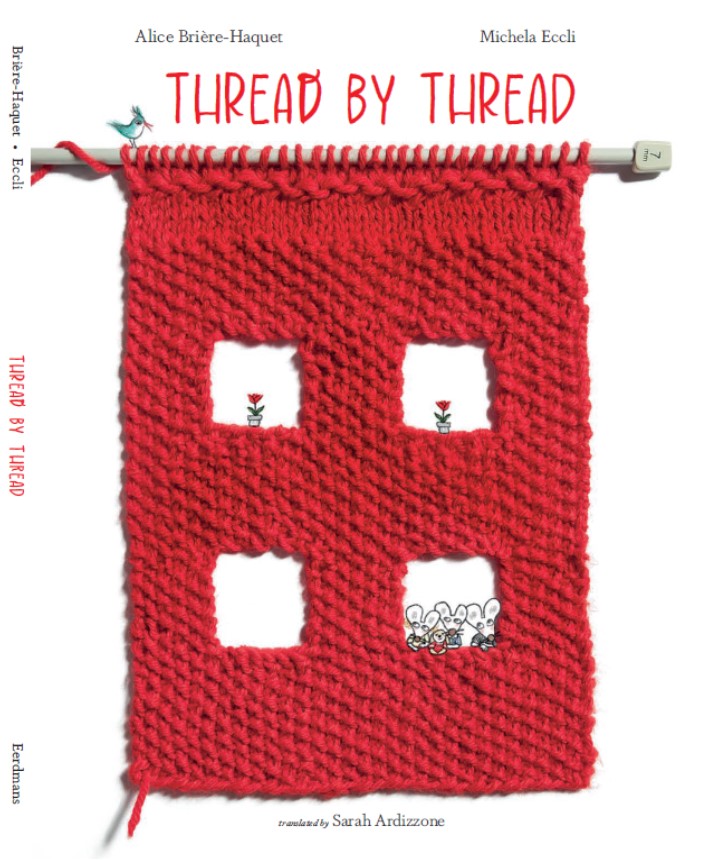

Thread by Thread– written by Alice Brière-Haquet, illustrated by Michela Eccli, translated from the French by Sarah Ardizzone

Eerdmans Books for Young Readers, 2025

“Knit one, purl one,” this book begins. Everyone who knits knows the phrase. Sometimes you drop a stitch, which is frustrating. Other things can go wrong. You may run out of the color yarn that you need, thinking that you had enough. In Thread by Thread, Alice Brière-Haquet and Michela Eccli have created several projects. The picture book is an homage to artisans, an ode to needlework, and a compassionate look at the need for everyone to find a home.

To call the illustrations inventive is an understatement. Delicate drawings of a mouse family intersect with photographs of yarn and knit items. The central item is a home, a red rectangle suspended from a knitting needle. Four square windows enclose two mice each, a flower, and a blank space. The demands on readers’ attention seem calm in this minimalist setting, but the book progresses to a warning, ending in reassurance.

As any knitter knows, “sometimes things can begin to unravel.” The mice have to hastily descend the stairs, which are a loose thread arranged in a zigzag. Frightening creatures emerge, including a dragon with orange fire emerging from his mouth. Brière-Haquet begins to describe the underlying resistance of this family: “We leave without making a fuss, but we dream of staying put.” The phrase could be a summary of some refugees’ experience.

While the dragon seemed menacing, other creatures are helpful. The rhino helping to hold thread called to mind Albrecht Dürer’s famous animal, which he had never actually seen, but whose combination of fantasy and accuracy amazed viewers. A turtle slowly rolls a ball of green yarn, and tiny crabs support a knitting needle. Again, the author introduces a quietly dissident note, admitting that the wool and silk are “spools of worry.”

Eventually, the mice create a new home. One window is still empty. The mice are proud and relieved. A seesaw works by balancing a group of small animals with a large one. Without a didactic trace, author and illustrator have presented several messages within one structure. This house holds anxiety, a cooperative spirit hope, and accomplishment. Thread by Thread is one of the most profound and beautiful picture books I have recently read. The elements of text and picture are interwoven in a way that will never unravel.