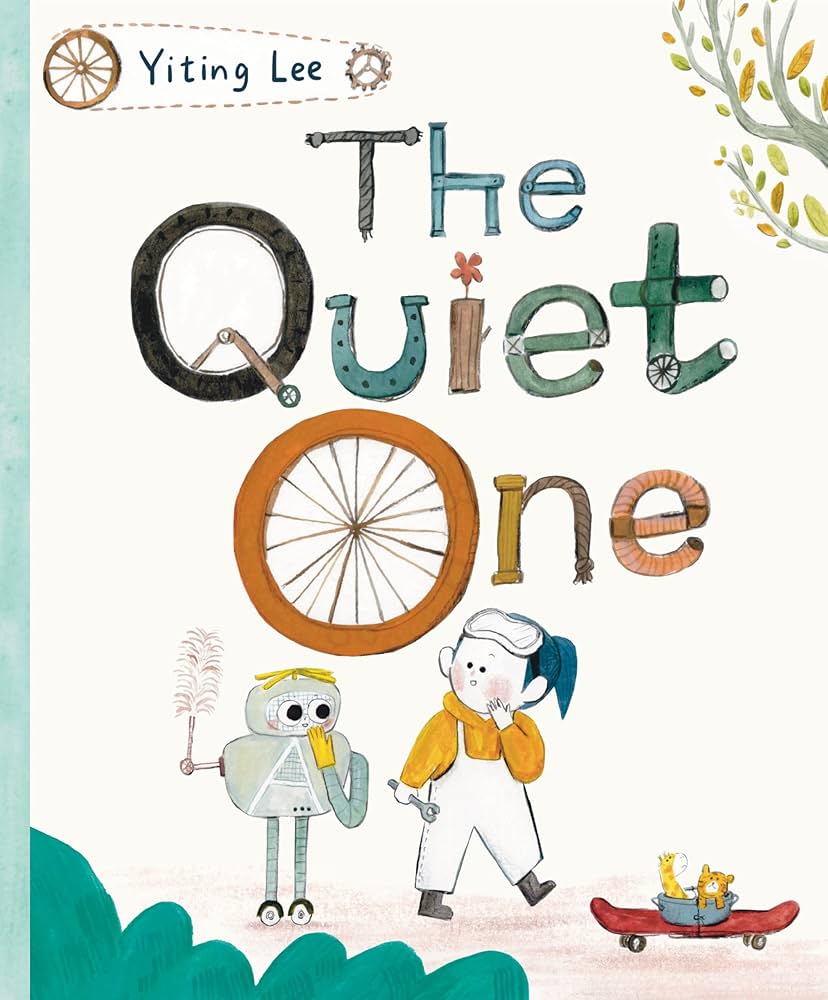

The Quiet One – written and illustrated by Yiting Lee

Eerdmans Books for Young Readers, 2025

There is a quietly reassuring message in Yiting Lee’s picture book about shyness. As carefully constructed as the robot that a young girl, Milly, constructs out of castoff materials, the story explains that not everyone needs to be outgoing, or brimming with obvious confidence. There is nothing wrong with those qualities, more obviously associated with success than being introverted. But not everyone fits that mold. Milly is one such child; she doesn’t need to radically change her personality. She needs to accept it, and to expect others to, as well.

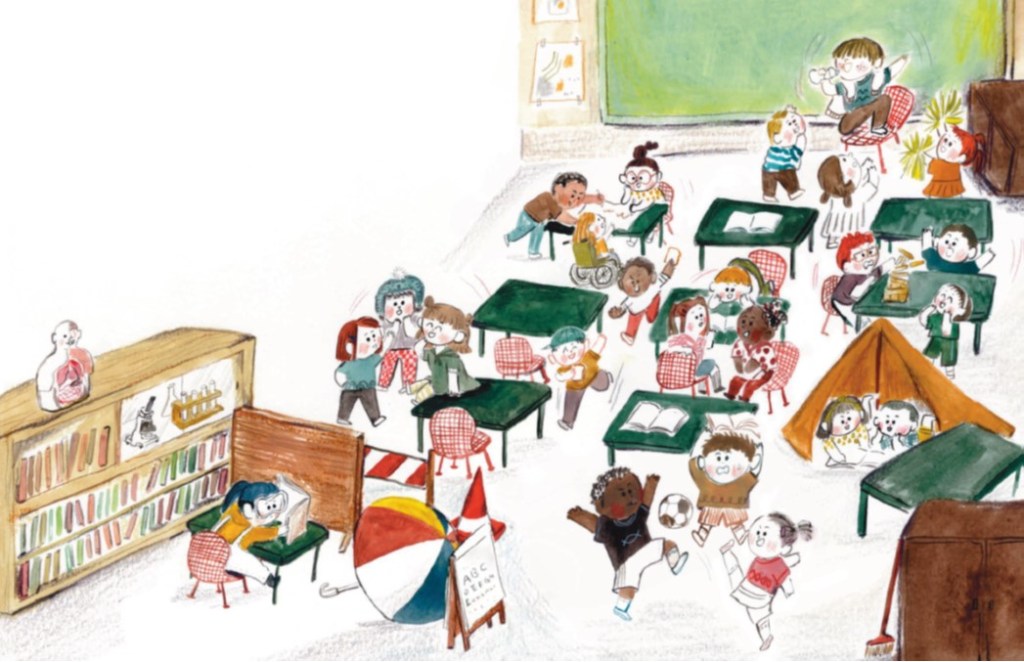

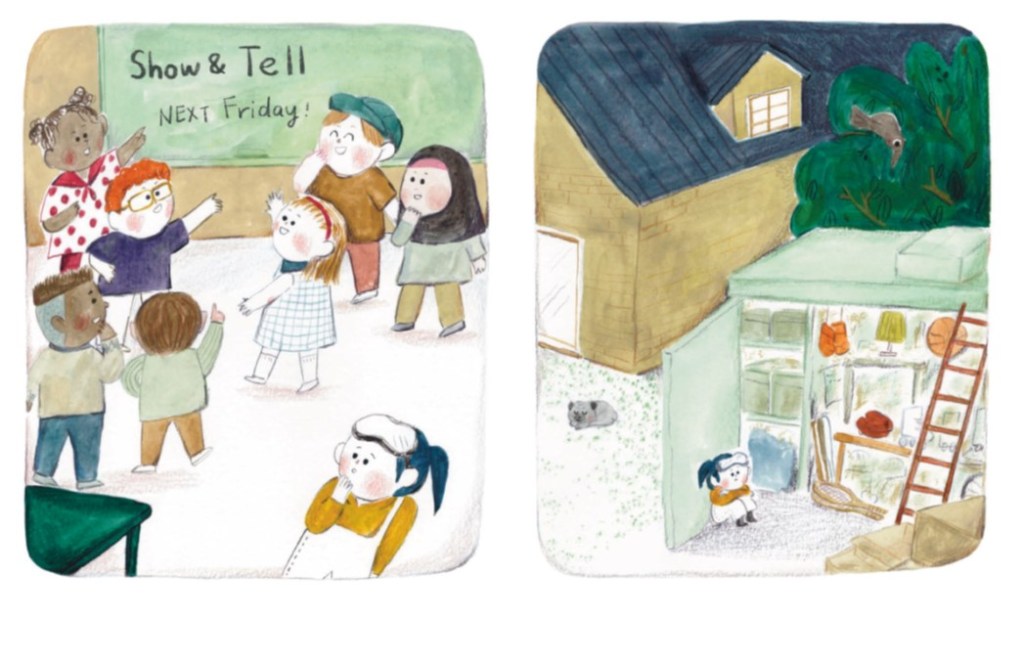

Milly’s classroom is full of active children. They are kicking a soccer ball, running in the aisles, and giving a pretend karaoke experience. The behaviors of these lively kids is not universal. Readers will note that there are other students reading and drawing. However, even they are engaged in conversations with one another, while Milly is alone, actually seated behind a wooden partition. Milly lacks a fundamental sense of who she is: “She wasn’t sure if she didn’t have anything to say, or just didn’t know how to say it.”

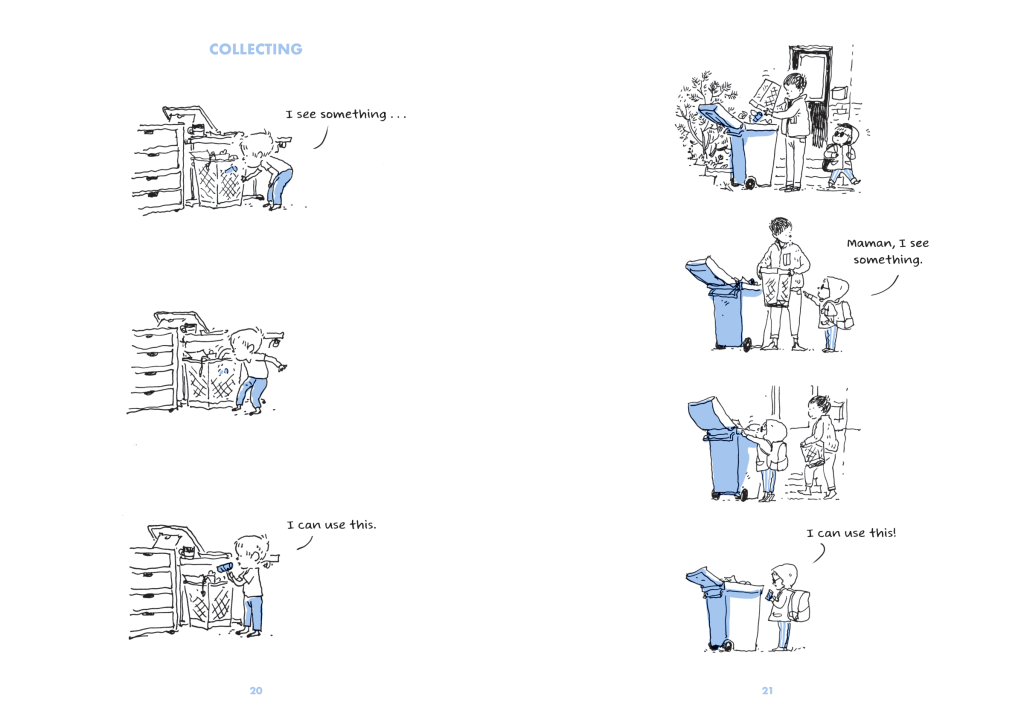

Mechanical skills are one of Milly’s strengths, even though she may not perceive them that way. Her “secret place” is a workshop full of recyclables and junk, a vast collection which she imbues with potential use. I am fascinated by Lee’s use of scale in illustrating this haven. On the first two-page spread, it appears on the second page, dwarfed by the preceding picture of students who are excited about an upcoming show-and-tell activity. Hovering in her workshop, Milly and her stuff appear dollhouse-sized in comparison with the previous scene. Only on the following two pages does the reader see the full-sized nature of her vocation. Lee’s illustrations are rendered in watercolor and colored pencils, digitally edited. The limited range of colors, small detailed images, and word bubbles mixed with text, all create a unified quality to the book. Milly is an artist as well as a mechanic. In her workshop, she gestures to a cartoon-like sequence of drawings showing the transformation of each single item into a wondrous contraption. She is gifted, and her insecurity is clearly rooted only in social expectations.

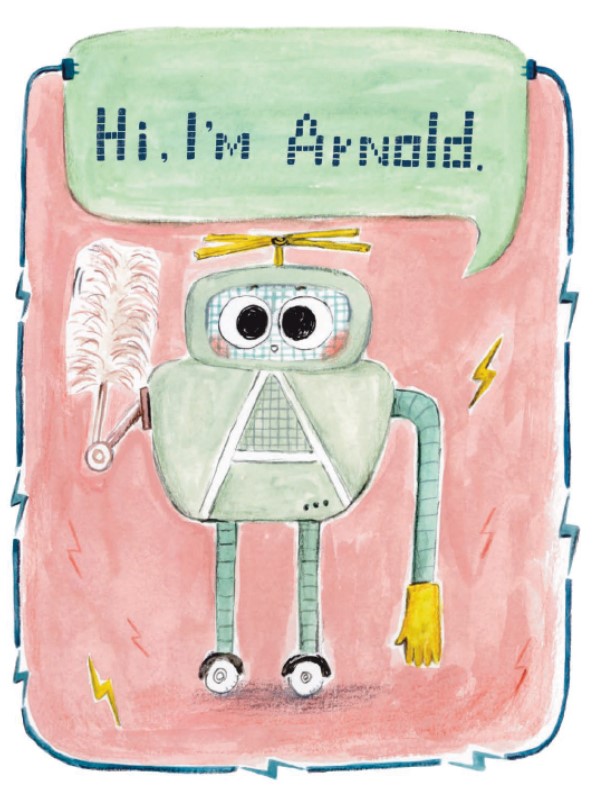

Finding a broken cleaning robot, Milly envisions a new use for it. She creates a kind of Frankenstein’s monster, but without the torment of that creature. There are two wordless pages, and then he emerges as Arnold, speaking in pixels. Arnold becomes just the first production in an elaborate amusement park of trash converted to delightful rides. Arnold, it turns out, can do more than just say his own name. He counsels Milly, advising her not to be afraid of bringing him to show-and-tell. Is he a personification of Milly’s own psyche? Adults will probably infer that, and children likely will not. The important part is the role that he plays.

Explaining Arnold’s origins to a rapt audience, Milly slowly begins to change. “She was so caught up in the moment that she forgot all about her fear.” Rather than an abstract resolution not to be shy, Milly learns through doing that her supposed weakness is actually a strength. Children who are shy will love this book, as will any adult who was a shy child, knows a shy child, or is still shy in adulthood. On the other hand, kids who happily play soccer in the middle of a classroom will appreciate its vision of human difference.