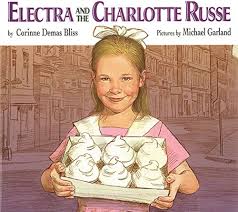

Electra and the Charlotte Russe – written by Corinne Demas Bliss, illustrated by Michael Garland

Boyds Mills Press, 1997

When I was growing up in New York, the charlotte russe was a popular pastry, though the peak of its popularity was already gone by the post-World War II era. At the time, I wasn’t aware that I was enjoying a part of New York food lore in its decline, but that still had meaning for my parents’ generation. In Electra and the Charlotte Russe, a Greek-American family, living in an ethnically mixed Bronx neighborhood, is the center of the nostalgic story. In her author’s note, Corinne Demas Bliss writes that the book is based a story which her mother, Electra, had related about her own Bronx childhood in the 1920s. Whatever your background, and whether or not you have ever eaten the delicate pastry enclosed in a paper sleeve, you will probably respond to the essence of Demas’s tale and Michael Garland’s almost photorealist pictures.

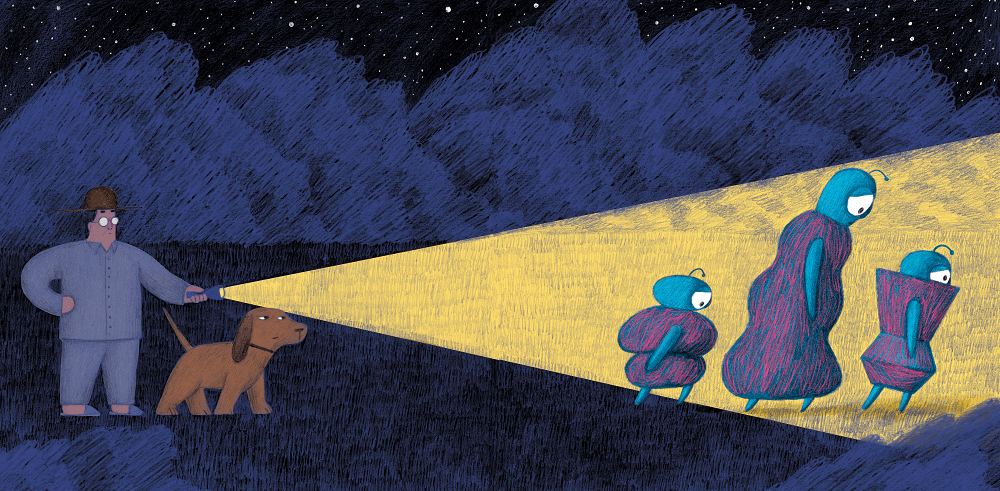

Once upon a time, there were many children’s picture books with extensive text. Electra opens with a portrait of the little girl and her mother. Electra is entrusted with an important errand. She will go to the local bakery to purchase six charlotte russes for her mother’s guests. These are Mrs. Papadapoulos, Mrs. Marcopoulos and her daughter, Athena. The guest without a melodic Greek last name is Miss Smith, who is learning Greek from Electra’s mother, in preparation for her upcoming marriage to Mr. Demetropoulis. If you think this is an overly idealized portrait of immigrant communities, the motive behind the Greek language lessons is for the future Mrs. Demetropoulis “to understand what his relatives said behind her back.”

On the way Electra meets her friend, Murray Schwartz, whose tongue has turned green from eating a gumball. A much older neighbor, Mr. Melnikoff, waxes nostalgic about the charlotte russes of his own past, calling them “a dessert fit for a princess.” The extended text occupies some pages, while others have only one or two sentences. A typical New York City apartment building, as rendered by Michael Garland, seems shaded in ombre light and colors, accompanied by the brief instructions to Electra not to run even though she is in a hurry. Mrs. Zimmerman at the bakery repeats that prophetic warning to her young customer.

When Electra trips, damaging the exquisite works of art in her bakery carton, she tries to fix them. This leads, of course, to eating some of the whipped cream. A two-page spread shows four scenes of Electra’s face and hands as she attempts to even out the cream. Every step of the process is detailed in sequence, from Electra’s entrance into her apartment building, to her settling on several landings with the pastries, and finally reaching her home. “They didn’t look quite like charlotte russes anymore, but at least they did look all the same.”

Fortunately, Electra’s mother had prepared other delicacies: baklava, diples, loukoumades and kourabedes. The guests enjoy the now transformed and unidentifiable charlottes russes. After they leave, Electra’s mother explains to her the concept of remorse. “Remorse is when you wish you hadn’t done something that you did.” But she isn’t angry with her daughter, and the book closes with Electra sitting on her mother’s lap. Perhaps she would have been less forgiving if her guests had not enjoyed the gathering, or the pastries denuded of whipped cream. But I doubt that would have made a difference.