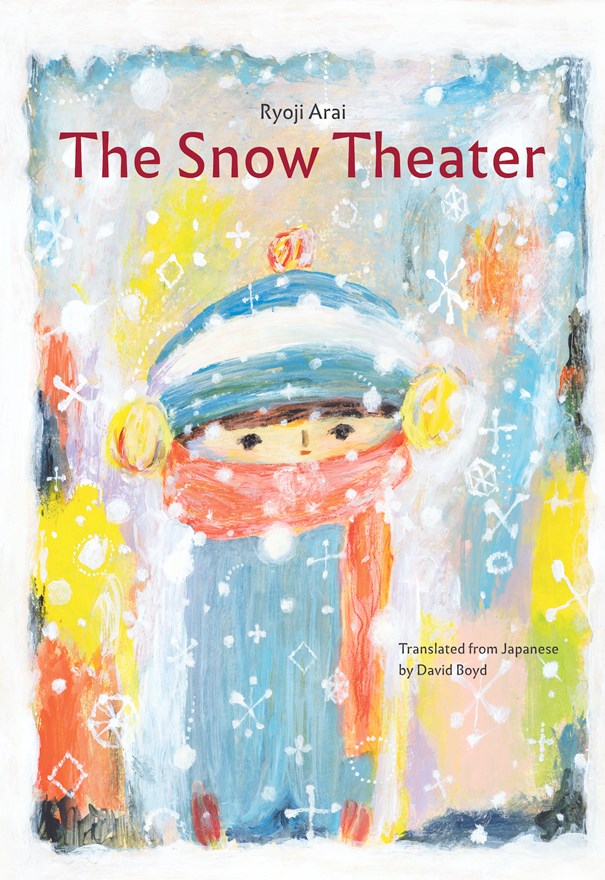

The Snow Theater – written and illustrated by Ryoji Arai, translated from the Japanese by David Boyd

Enchanted Lion Books, 2025

The art of Ryoji Arai’s The Snow Theater demands strong adjectives: intense, stunning, original, but also: unpretentious, dream-like, and accessible. The reason for this contrast, aside from the artist’s incredible gifts, is the imagery’s blend of naiveté and sophistication, with splashes of color as well as carefully delineated figures. Arai’s pictures capture what it feels like to be a child, and specifically to be captivated by the experience of snow. Snow as theater is not at all artificial, from a child’s point of view. It is a gift, perhaps unanticipated, that then takes on different qualities, including joy. It is familiar, but can also be strange.

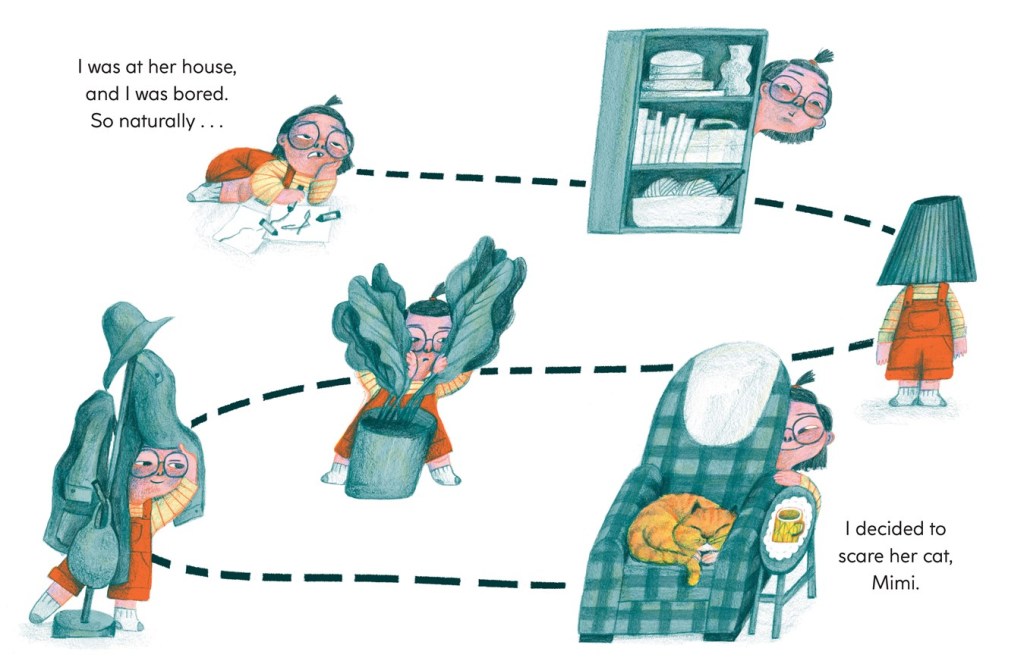

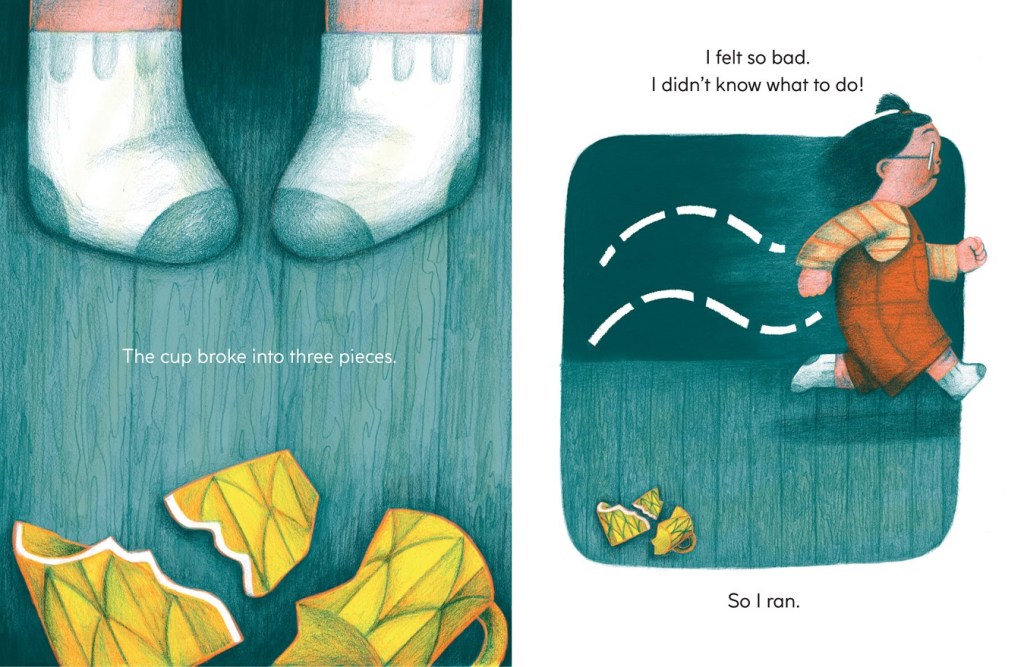

There are innumerable children’s picture books about snow, and many are excellent, beginning with the Ezra Jack Keats classic The Snowy Day (see some other examples here and here and here and here and here and here and here). The Snow Theater is not unique, but both its design and philosophy and language are distinctive enough to merit acclaim (it is translated by David Boyd, who has translated some of the Chirri and Chirra books, also published in English by Enchanted Lion). It opens indoors, where two boys are “keeping warm” and “looking at a book.” The first picture has the reader looking towards them from outside, where they are framed in the window, almost like residents of a dollhouse. Then, a two-page spread is divided into several more specific descriptions of their activity, and one larger scene of it result. At first they are sharing a picture book about butterflies in a cooperative spirit. Then, the friend of the boy who lives in the house “badly wants to borrow the book,” and the idyll is ruined. That adjective, “badly,” prepares you for the act of, perhaps accidental, aggression that results when the book is damaged.

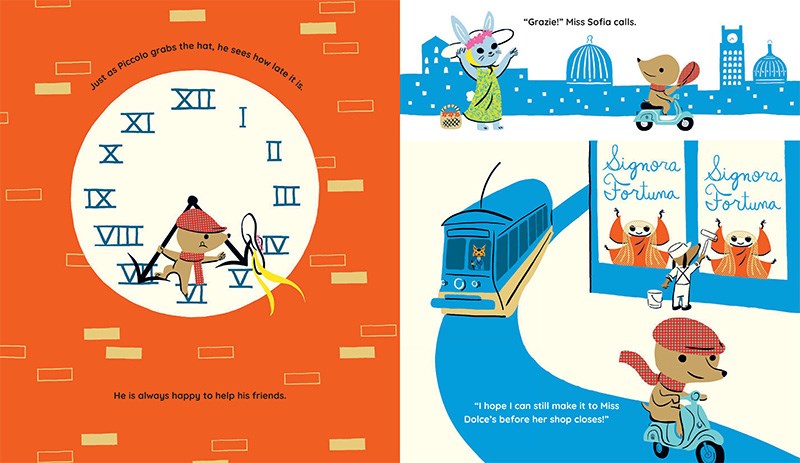

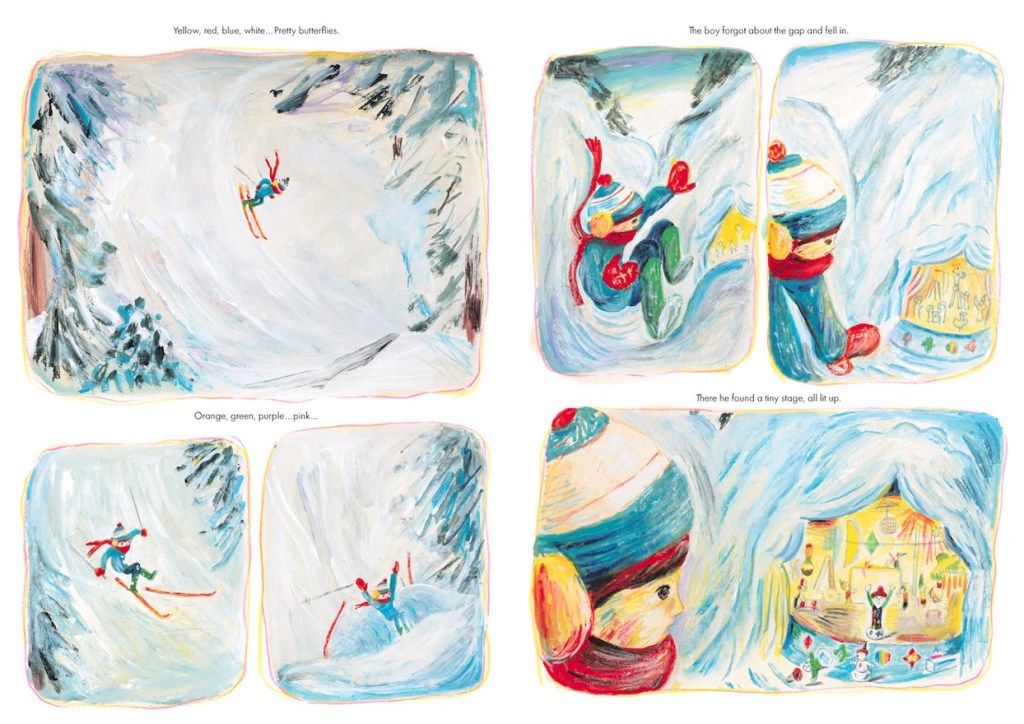

Now the boy is devastated. Worse, the book is actually one of his father’s favorites, adding a dimension of anxiety to an already tense situation. Arai traces the arc of the boy’s feelings. They boy had wanted to share the book with his friend, not only because they both liked butterflies, but in order to communicate its special status in his family. Worried, he leaves the house and begins to ski through the snow. Suddenly, he finds himself looking into a miniature theatrical production. There are “snow people,” including ballerinas. They surround him physically, occupying his senses. Then the scale seems to change, as he sees “a large theater in front of him.” Yet the performers, who include singers, still appear to be tiny. “Everybody floated quietly to their places, like freshly fallen snow.” There are echoes of Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker, with impressionistic colors. Snow people reflect the color of rainbows. Icicles are suspended from their limbs and odd pieces of scenery, like an Easter Island head, occupy the elaborate background.

Then the show ends. As in The Nutcracker, viewers wonder if the performance was a dream, or if the protagonist had really undertaken a mysterious journey. The kinetic, and ephemeral, experience of a snowstorm seems to have been the boy’s escape from emotional difficulty. He reaches across the snow to find his friend against a field of butterflies, only some of which are enclosed within a book. The boy’s father appears with the awaited resolution: “Let’s get you home.” A cup of hot cocoa by a warm stove brings back domestic security, but the song of the snow people is reprised in the boy’s memory.