Little Shoes – written by David A. Robertson, illustrated by Maya McKibbin

Tundra Books, 2025

Many Indigenous children, in both Canada and the U.S., suffered the trauma of being removed from their families and placed in residential schools funded by the government and often controlled by different Christian denominations. Deprived of their heritage, and often subject to physical and emotional abuse, these children would be lost to history if not for concerted efforts to publicize their experience and to demand restitution and atonement. Little Shoes is a picture book by acclaimed author David A. Robertson (see my reviews here and here and here), a member of Norway House Cree Nation, illustrated by Maya McKibbin, of Ojibwe, Irish, and Yoeme heritage (Robertson and McKibbin have collaborated before). They have taken on the weighty task of presenting a catastrophic loss to young readers, but also offering hope and determination. With poetic text and images of family life that are both familiar and mystical in tone, they have achieved this goal.

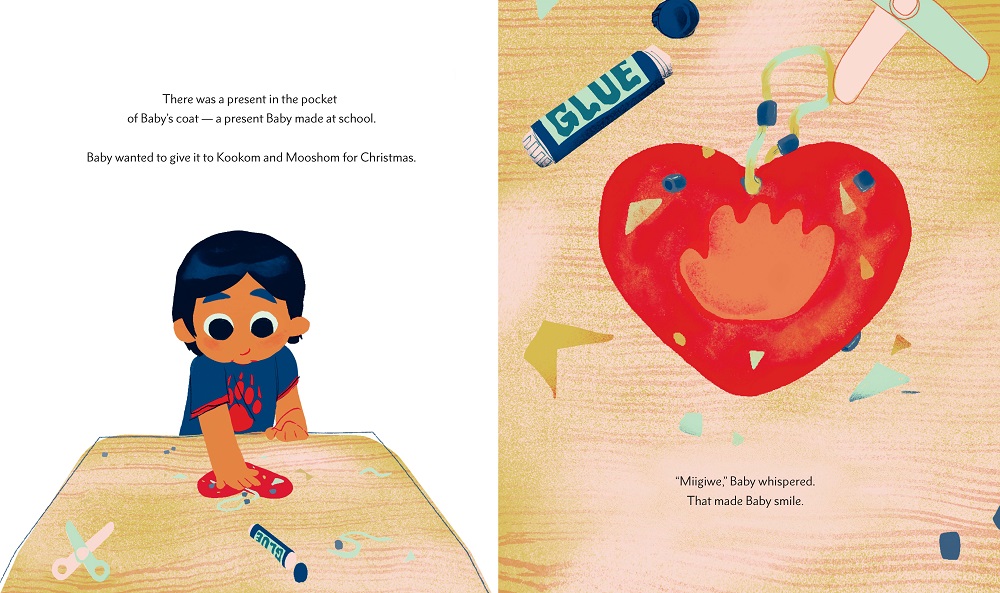

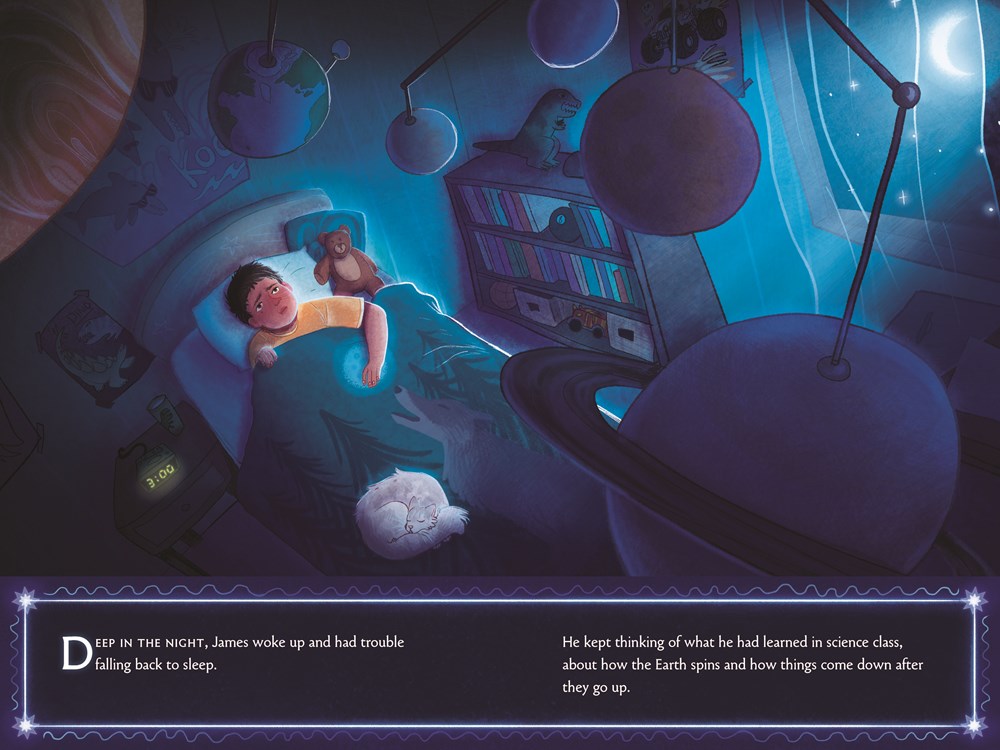

The endpapers feature constellations, introducing a central theme of each person’s place in the universe. James, who understands the principles of astronomy from his science class, opens the curtains in his room to the moonlight. He asks his mother to clarify how and why his feet remain firmly on the ground if the Earth is spinning in space. The answer is only one of several which his mother will frame truthfully, and also use to elaborate on other questions which will naturally follow. She reassures him that his Kōkom’s, (grandmother’s) explanation about their origins is valid, but adds, “even though you’re from the stars, your home is right here with me.”

The love between a parent and child, and the enveloping warmth of his community, are anchors in James’s life. His intense curiosity places demands on a parent who is obviously committed but exhausted, when he returns to her room with a request to hear about “every single constellation,” His own attempt to visualize and trace them in the night sky is insufficient. The dialogues between children and their caregivers are open ended, and the book swerves from the dimensions of the cosmos to the specific history of injustice that remains unresolved.

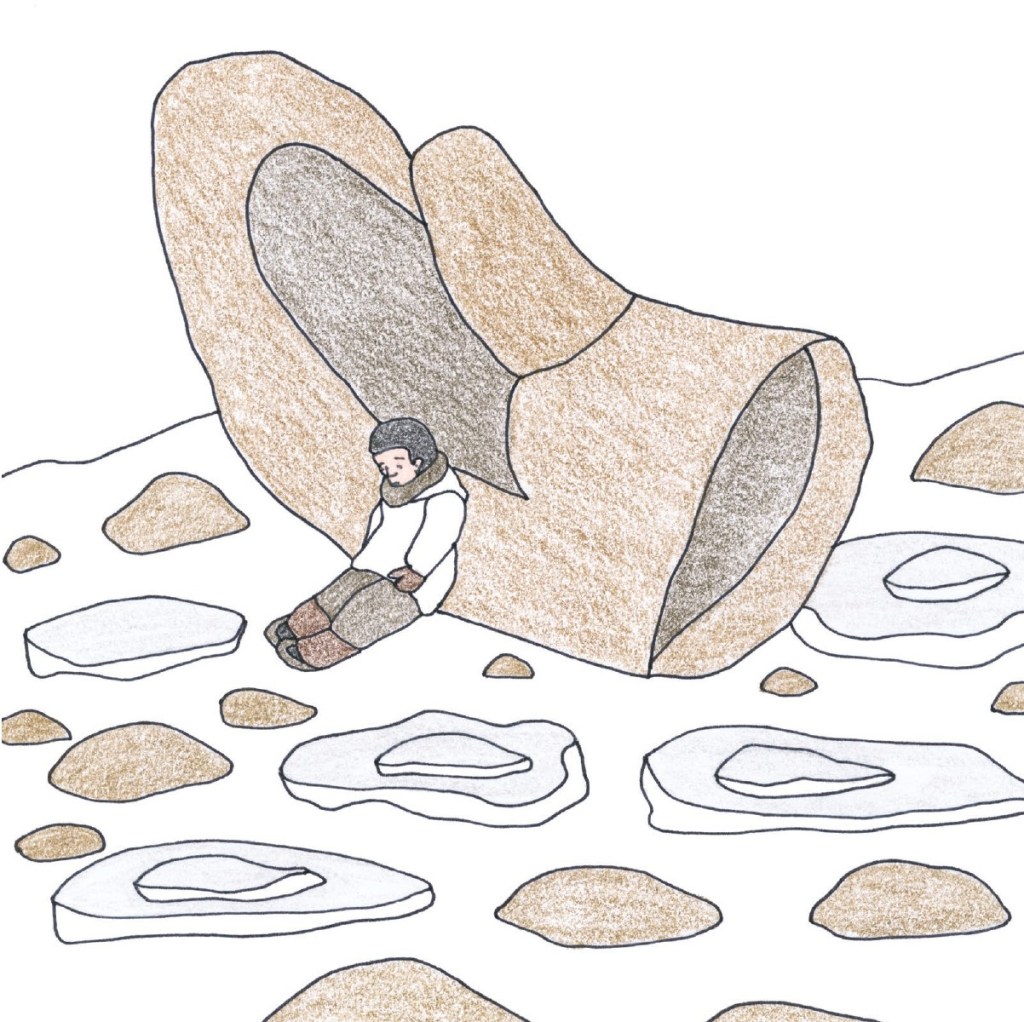

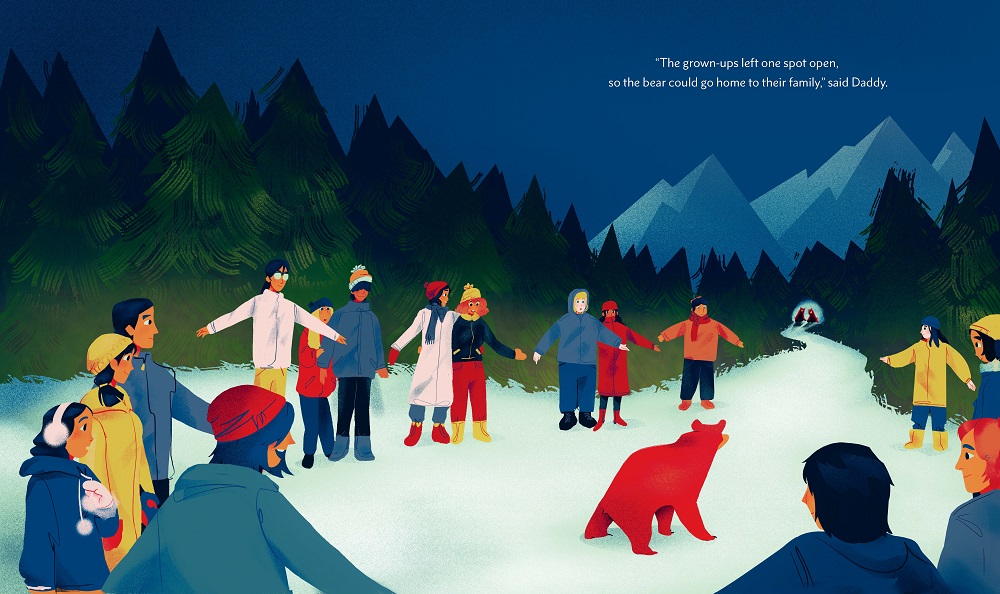

James and his kōkom set out for one of their frequent walks, but his time it is transformed into a march. A daily experience becomes a metamorphosis, and his grandmother takes on the role of teaching about a part of their lives that is far more difficult to internalize that the motions of the planets. The little shoes of the title are those of Indigenous children whose deaths are acknowledged by Kōkom with the haunting phrase that they “had gone to residential school but had not come home.” Shoes as a metonym for children who have died seems to capture a sense of a life that is unnaturally cut short. Other articles of clothing are perhaps less universal, and small shoes also reflect the scale of the children relative to adults, both those who loved them and those who inflicted torture. A similar allusion to this loss has been used in many memorials to child victims of the Holocaust. (Of course, while some of those children, like the Indigenous victims, died of abuse, neglect, and disease, many were murdered immediately upon arrival at a death camp. Chronicling atrocities requires acknowledging both what they share and common and how they differ.)

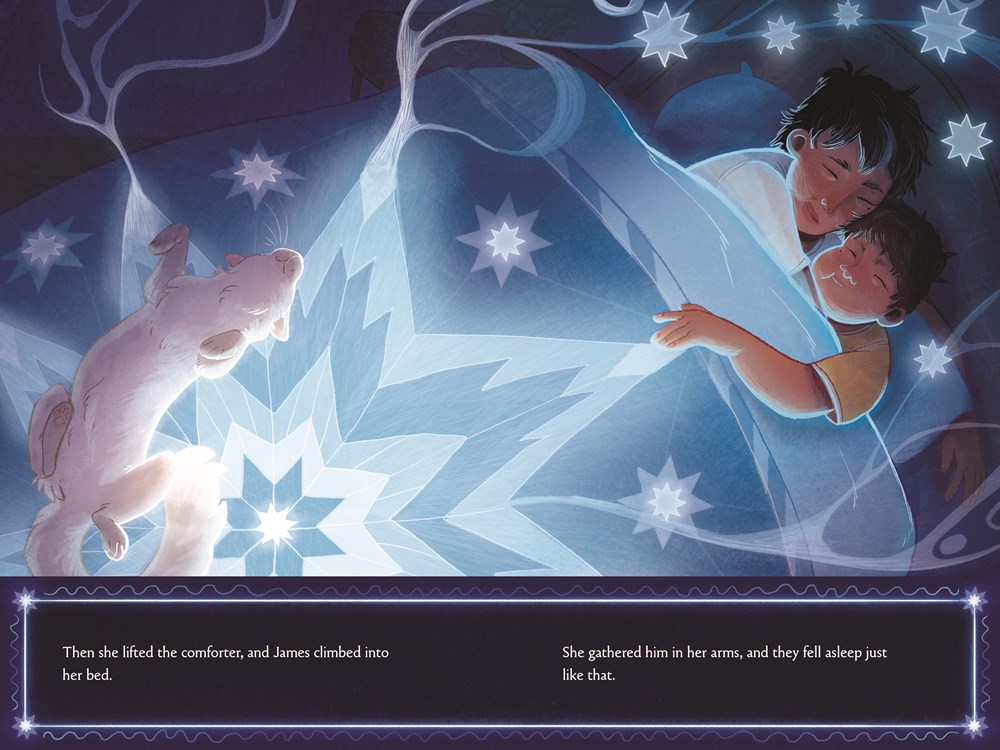

Robertson and McKibben do not attempt a simplistic response to James’s fears. He interprets the frightening facts through the lens of loneliness, asking his mother how his own grandmother had coped with the deprivation of her isolation in the residential school. His mother responds that her sister and she had “cuddled,” paralleled by McKibbin’s image of mother and son sharing the same physical contact. Their bond is unbreakable, even if mitigated by anguish. The honesty of Little Shoes is an antidote to fear.