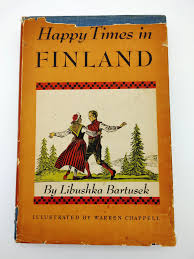

Happy Times in Finland – written by Libushka Bartusek, illustrated by Warren Chappell

Alfred A. Knopf, 1941

Everyone knows that Finland is allegedly the happiest country in the world. You certainly can’t take these simplistic measures too seriously, and comparing Finland to other countries with entirely different histories, economies, and demographics is useless. I recently reread an unusual childhood favorite, which I had bought at a library used book sale. Its appeal to me at the time remains vague. I would read almost anything, and it had lovely pictures and promised to tell a story about a distant part of the world. Happy Times in Finland, by Libushka Bartusek, was published in 1941. At that point, it was indisputably not happy at all. Having been invaded by the Soviet Union, they eventually allied with Germany in that country’s war with its Russian enemy. This was a bad choice, but it is not reflected in the book, which takes place in the idyllic time period before the war.

There is minimal plot and character development in the book, but a lot of folklore. To summarize the improbable premise, Juhani Malmberg, a Chicago Boy Scout with Finnish immigrant parents, goes to visit his ancestral homeland. He is able to take this expensive trip due to the generosity of his father’s employer at a furniture factory, Mr. Adams. Finland is known for, besides an improbable level of happiness, abundant high-quality wood. A furniture manufacturer would be eager to see firsthand the source of his best supplies. Since Mr. Malmberg is such a loyal employee, his benevolent boss actually takes Juhani along, for free! He has the opportunity to see his beloved grandparents, as well as his aunt, uncle, and cousins. In addition, Juhani becomes an ambassador from the American Scouts to their Finnish counterparts. Aside from missing his parents, there’s a lot of happiness here.

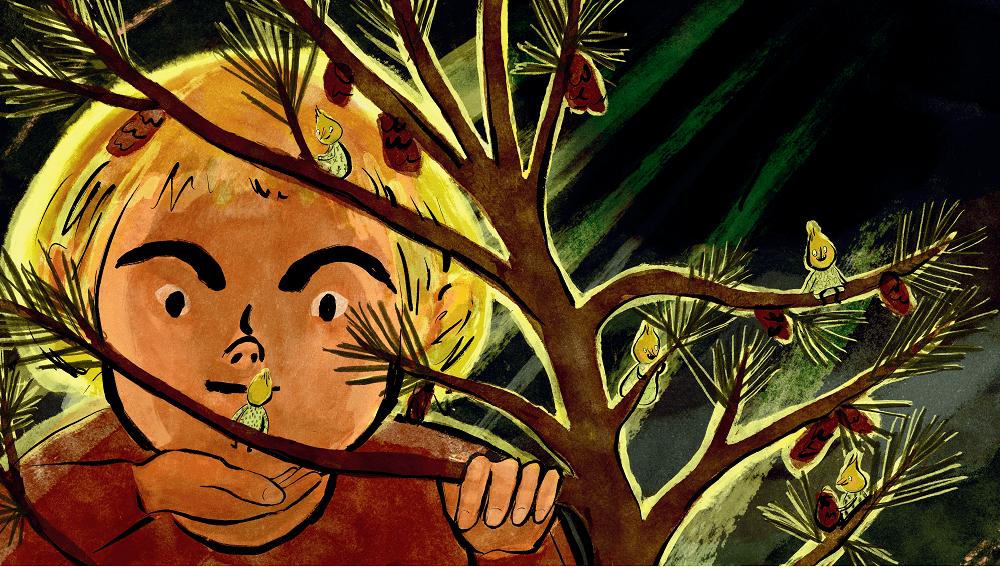

Poetic language fulfills expectations about a land endowed with natural resources, and steeped in literature. Approaching land, Juhani seems to be expecting a myth and he finds one: “Sure enough, there it was, just as his mother said it would be: an expanse of water, blue as sapphire, with green islands dotting it, as though some giant had scattered a mammoth handful of emeralds on a silver-streaked scarf.” Not only the environment, but its people, are described with hyperbole. Oddly, almost everyone is blond. Finland has a Swedish minority; the name “Malmberg” indicates that his father’s family is descended from this group. His cousins’ last name is Kallio, of Finnish origin.

Finnish is not a Scandinavian language, but is related most closely to Estonian and Hungarian. (A glossary of Finnish words is included at the end of the book.) Here is a description of Juhani’s aunt, a veritable Amazon of pale beauty: “She was tall and blond, so blond, in fact, that Juhani thought she was white-haired…she had great dignity…he felt as though he were at the feet of some exceedingly beautiful statue, all made of silver and bronze and pearl…her teeth gleamed like mother-of-pear.” There are even references to “Viking blood.”

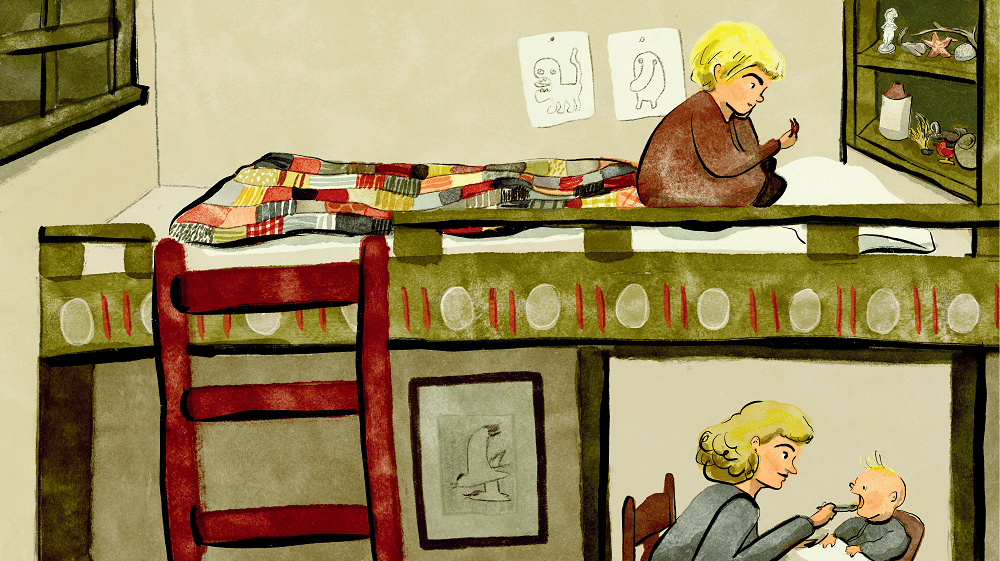

The few realistic elements stand out because of their minimal role in the story. Aunt Kallio, Aiti to her children, has favorites among her offspring. Her older son, Jussi, will vicariously fulfill her own dream by becoming an architect, a career closed to women. Eero, the younger boy, is not academically oriented. Unlike his parents, he prefers manual labor. She keeps her disappointment to herself, only thinking how he lacks “initiative.” “Oh, me! she sighed, one could not be everything.” This statuesque symbol of perfection is unable to tolerate individual differences.

Warren Chappell’s illustrations, some in color and others sepia, appear to be lithographs. They are stylized images, whether portraying men in a sauna or women clothed in traditional costumes for festivals. There is a haunting image of a blind storyteller who recites Finnish epic poetry. Mr. Adams recognizes that the Kalevala’s metrics had influenced Longfellow’s composition of Hiawatha. The Old World and the New touch one another in this tale of immigrant roots, written as the shadow of fascism descended on Europe. It’s blatantly out-of-date and also oddly appealing, just for that reason.