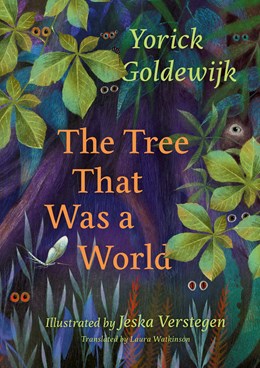

The Tree That Was a World – written by Yorick Goldewijk, illustrated by Jeska Verstegen, translated from the Dutch by Laura Watkinson

Eerdmans Books for Young Readers, 2025

The Tree That Was a World is unexpected. The central premise of a multitude of creatures who all inhabit, or interact with, the tree, and the dream-like mixed media illustrations, predict a kind of eco-fable. While the natural environment is the scenery to the story, its idiosyncratic characters form a unique cast that defies any didactic message. Readers will meet two pikes, one of whom finds the other to be “arrogant and self-important.” There is a big brown bear having an existential crisis, and an owl who doubts his own identity. These are animals who argue, become discouraged, and pronounce, “Fuhgeddaboudit” when they reach their wits’ end.

The tree is majestic, a metaphor for age and stability. It’s also a place where everyone has a distinct niche and harmony is not always the order of the day. A moon moth caterpillar contemplates the meaning of freedom. Her friends boast and obsess with their beauty, while she finds herself unwilling to play their game. All the characters are similarly endowed with an independent spirit, which is far from idealized. They can be cranky and irritating, even while their refusal to conform is admirable. No, this is not George Orwell’s Animal Farm. Yorick Goldewijk’s carefully expressed irony sets them all, from spider to barn swallow, apart from allegory.

Jeska Verstegen’s pictures are dark, with dashes of illumination (I’ve reviewed her work here and here). A sloth determines to defy expectations, swinging gently from the tree. He projects his thoughts onto everyone who assumes they know him, even when they don’t, declaring that “he’s going to do some running, jumping, and somersaulting. And screaming. Lots of lovely screaming.” The angry pike swims by his nemesis, insistent that his distress is all the fault of the other fish. Oddly, the glassy green of this image reminds me of Martin and Alice Provensen’s illustrations for Margaret Wise Brown’s The Color Kittens. Yet for all the innocence of the lovely Golden Book classic, there is a mysterious depth the images, along with Brown’s poetry, share. The characters are anthropomorphic, but retain their identity as animals.

Other classic works of children’s literature will come to mind, including The Wind in the Willows, Winnie-the-Pooh, and even Frog and Toad (not to mention George and Martha.) A red squirrel gets into a heated argument with a toad, which includes a debate about the existence of gnomes, and the danger of socializing with humans. “If you’re not careful,” the toad warns, “you’re going to turn into one of them.” Children and adults will both take to heart those words to live by in this bold story, as non-compliant as the tree’s peculiar, yet also familiar, residents.