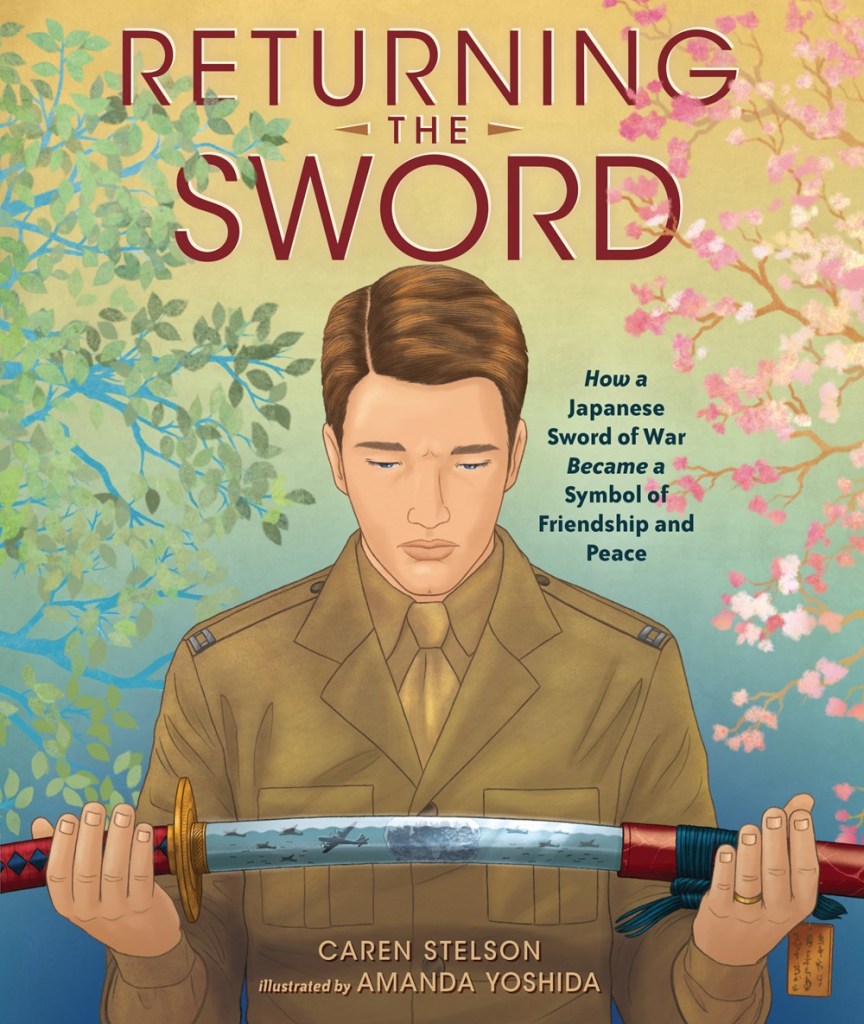

Returning the Sword: How a Japanese Sword of War Became a Symbol of Friendship and Peace – written by Caren Stelson, illustrated by Amanda Yoshida

Carolrhoda Books, 2025

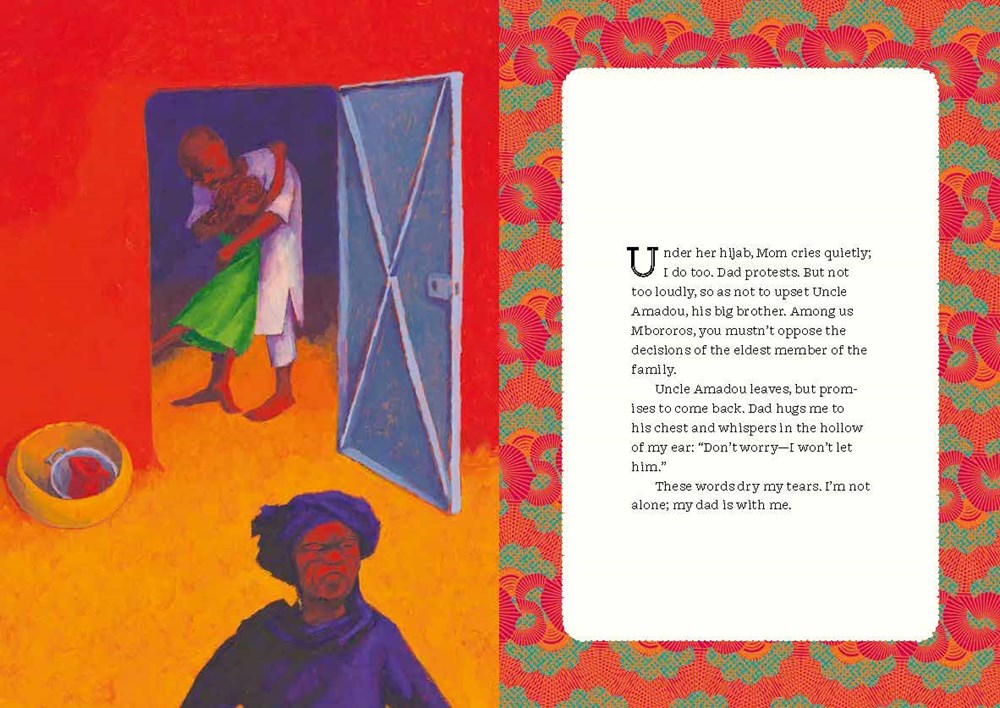

There is an understandable connection, for many readers, to books that promise a hopeful vision of reconciliation after conflict. I have read and reviewed many books in this category. While I respect the principle of deriving a positive lesson from a disastrous historical event, I have difficulty with facile messages of friendship in the absence of context. Returning the Sword has beautiful illustrations by Amanda Yoshida, and the text by Caren Stelson is obviously the product of sincere beliefs. She is a serious author committed to writing about important topics. However, I am troubled by the book’s almost complete absence of accurate information about Japanese aggression before and during World War II, and its depiction of the Japanese people as the sole victims of that conflict (as was also done here).

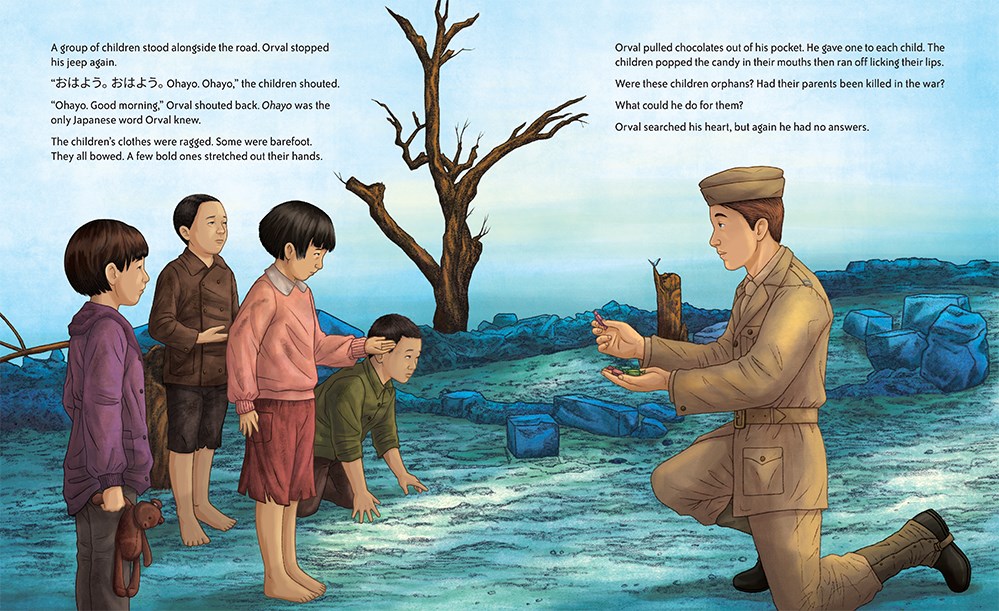

Stelson relates the story of Orval Amdahl, a man who served in the U.S. Marines during World War II and in the postwar occupation of Japan. He was horrified by the death and destruction wrought by the atomic bomb, a response shared by people throughout the world. Although more people were actually killed in the firebombing of Tokyo, inflicting death by radiation poisoning in the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was conceived as a different category of weapon, one to be avoided ever again.

The decision to use that weapon to end the war, while one with terrible consequences, did not occur in a vacuum, but readers would never learn that from the book. Reporting Captain Amdahl’s reaction in Nagasaki, Stelson writes that “The city had been destroyed by a terrible bomb,” and “So many people had lost nearly everything important to them in this terrible war.” The starving children he meets, and the other civilian victims, had been living under a fascist regime that inflicted torture and murder throughout the countries they occupied, and upon the Allied soldiers who fought against Japan’s imperial forces. The Rape of Nanking, the Bataan Death March, the abuse of Korean “comfort women,” and other atrocities, are completely absent, not even indirectly suggested in an age-appropriate way. I am not suggesting that these sources be directly presented to children, which would be totally inappropriate, but they could be offered as a context for adults sharing the book, since Japanese suffering is uniquely at the center of its message.

Like many soldiers who served in the Pacific, Captain Amdahl returned home with a souvenir sword. This item continued to plague him psychologically, and he ultimately decided that he would like to return it to, as he interpreted it, its “rightful owner.” Stelson describes the swords as works of art and family treasures. The craftsmanship used to create them is somehow allowed to displace their actual purpose as symbols of military might, and also, to a lesser extent in World War II, as actual weapons used to perpetrate atrocities I prefer not to describe here. The U.S. military leaders who encouraged soldiers to appropriate them are cast as heartless. Captain Amdahl enters a room where the swords are “piled eight feet high,” and selects one to take home. This scene struck me as an inversion of the often-described encounter between the liberators of Nazi concentration camps and the bodies they discovered. The swords themselves are personified as lifeless victims.

Eventually, Captain Amdahl contacts Tadahiro Motomura, the son of the sword’s owner. Mr. Motomura writes of how his father did not talk about the war, but expressed his sadness at the loss of his sword: “At the end of the war, it hurt him to give it up.” (Without describing atrocities, the author might have suggested the incomplete nature of this statement. Even a mild indication of its irony, such as “The Japanese had caused great suffering in the countries they occupied. Still, Mr. Motomura felt sad about the loss of his family heirloom,” would have been closer to the truth.) Unlike in Germany, where an incomplete, and ultimately truncated, version of denazification was U.S. policy, in Japan a decision was made, in the context of the Cold War, to avoid forcing responsibility on the defeated nation. The emperor remained as a figurehead and there was virtually no educational program to ensure that the Japanese understand anyone’s suffering other than their own.

Captain Amdahl and Mr. Motomura believed that their personal reconciliation had embodied the idea of “peace with honor.” Perhaps if they had each come to terms with the historical realities that brought so much destruction, culminating in the terrible choice of using an atomic weapon, their decision would have been more meaningful. The book’s visual beauty, and even the ideal of reconciliation, could prompt a serious discussion with children about the consequences of both totalitarianism and violence. Historical facts and the idea of accountability would need to be part of that dialogue.