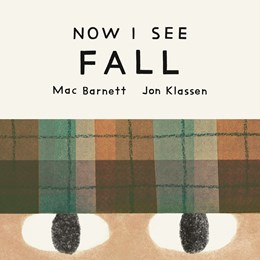

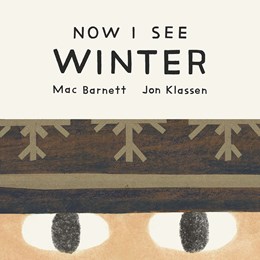

Now I See Winter

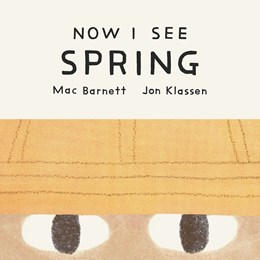

Now I See Spring

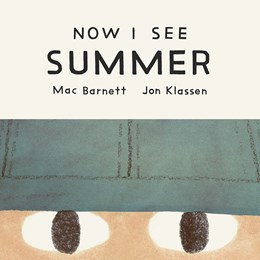

Now I See Summer

Now I See Summer

Written by Mac Barnett, illustrated by Jon Klassen

Tundra Books, 2026

There are board book editions of children’s classics, others that are original stories, and many that have tactile elements or photographs of familiar objects. All those categories are wonderful for introducing literacy to babies, toddlers, and young children. (Older children, and adults, also appreciate the sturdiness, portability, and other features of this format.) Mac Barnett and Jon Klassen have written and illustrated a systematic view of the four seasons based on two different premises, continuity and change. The four books are inventive and appealing, and surprising, as well. Even if you own many seasonal books for young readers and listeners, these are different.

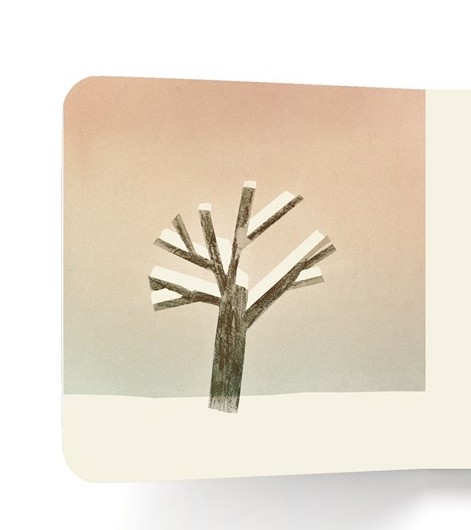

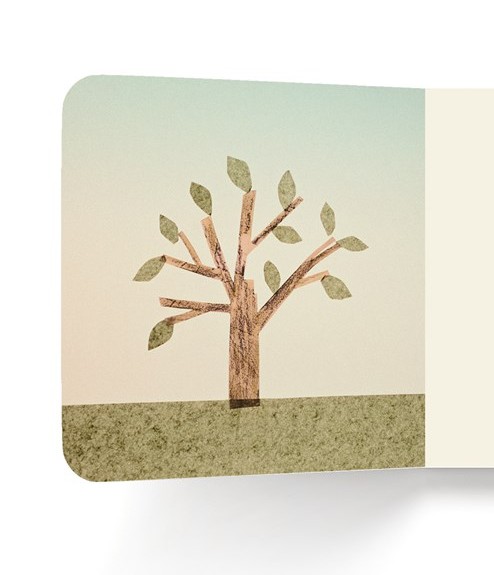

Each of these small, square, books has identical text, and pictures of the same location or object, varied according to the time of year when it is experienced. Each has a similar cover, featuring a pair of eyes ready to focus, and a color and pattern specific to winter, spring, summer, or fall. The tree is covered in snow in winter, accented with green leaves and grass in summer.

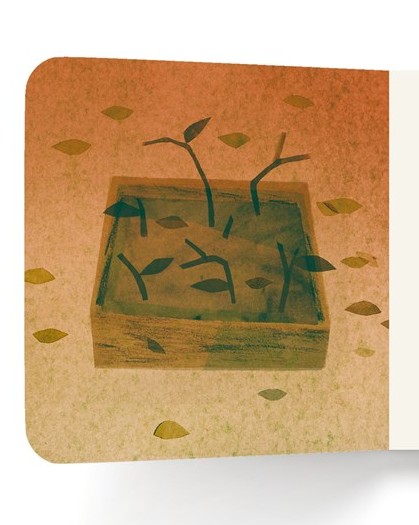

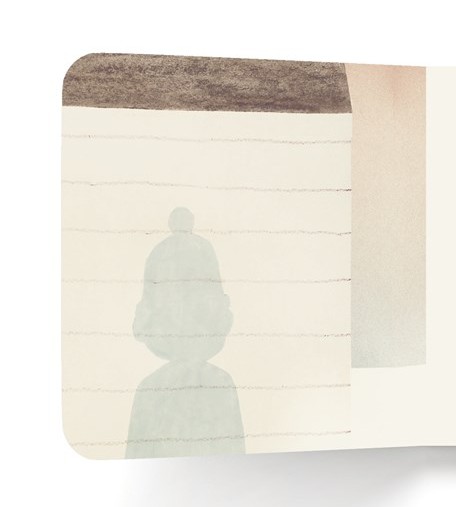

The garden, encased in a small box, is beginning to sprout in spring, and in transition between growth in the fall and emptiness in the fall. The page dedicated to “me” shows a child’s shadow observing the changed scenes. The simplicity of the text is a sign of its depth, a kind of Zen-like approach to the changing environment in the perception of a child. There is nothing inevitable about Barnett’s choice of few words. One page in each book is dedicated to “something red;” the fall image of a lone red wagon calls to mind William Carlos Williams’s famous red wheelbarrow. “The perfect hat,” of course, Jon Klassen’s hat trilogy. The hat changes for each season, but the child’s intent stare through the window is constant, a reminder that the book is about observation. Children do not miss some details that adults might, and they may attach different significance to them.

The series celebrates the acute perceptions of childhood, both for children themselves and the adults who recollect the time when a house, tree, or the expanse of sky were both predictable and strange, depending on time.