Hello Baby, It’s Me, Alfie – written by Maggie Hutchings, illustrated by Dawn Lo

Tundra Books, 2026

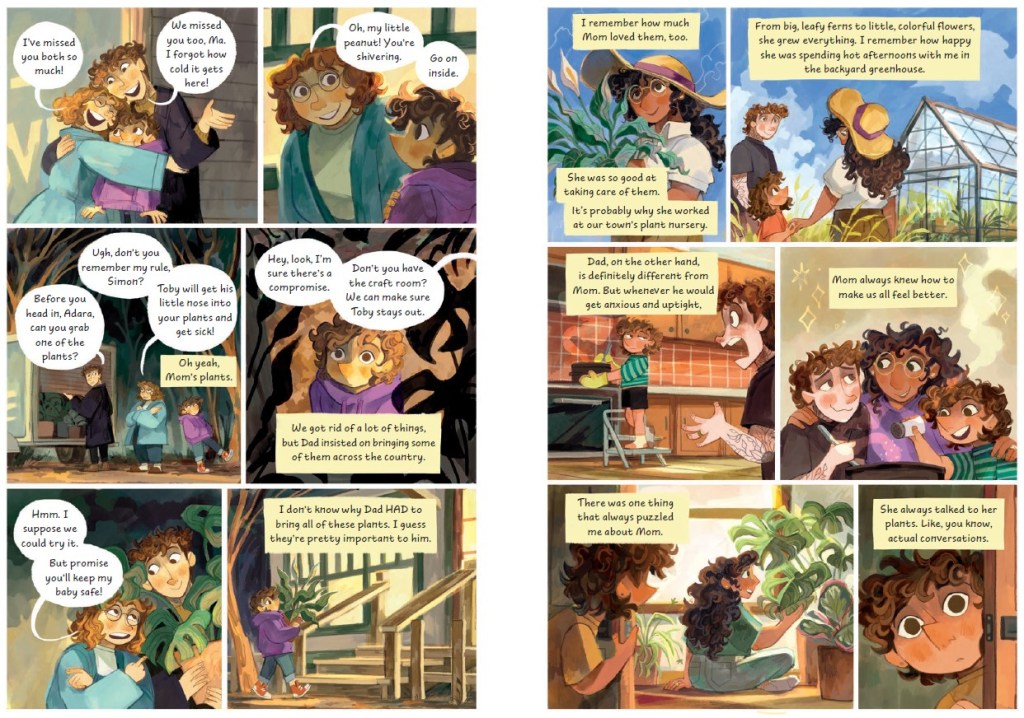

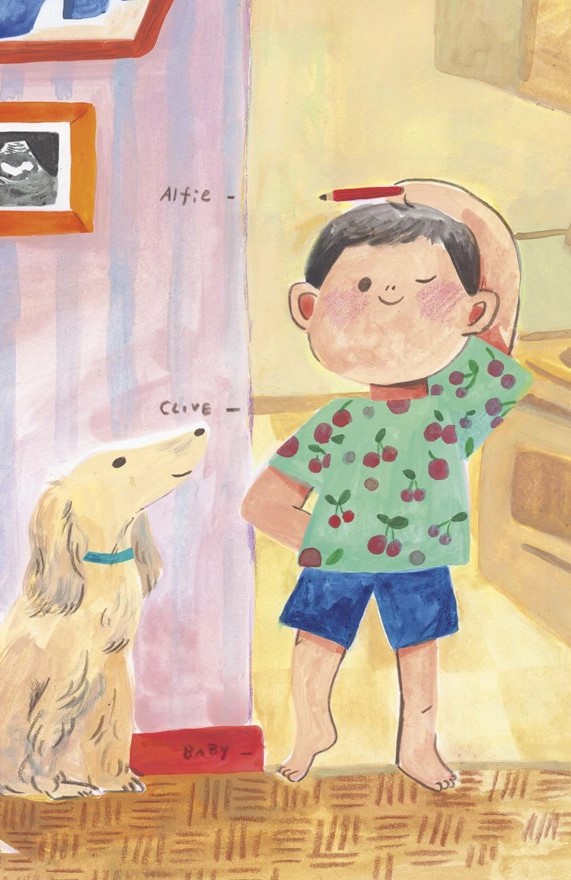

A long time ago, 1938, or 1931 if you lived in France, Babar the Elephant learned of his triplets’ birth with the sound of a cannon. Since them, many more children’s books have appeared with the purpose, more explicit than in the work of Jean de Brunhoff, of preparing older siblings for the birth of a new baby. Hello Baby, It’s Me, Alfie belongs in the top rank of these works. Narrated from the point of view of Alfie, the soon-to-be big brother, Maggie Hutchings’ and Dawn Lo’s picture book is totally believable. It is also artistically distinguished, illustrated with vibrant colors reminiscent of Fauvist painting, rendered with pencil crayons and gouache. Hello Baby is funny, tender, and thematically consistent. Each page is full of carefully composed images placed at varying angles, adding up to fully realized home life, both indoors and outside. When Alfie promises that “my heart is pretty big. So I’m sure I’ll find space for you,” your own heart will resonate with empathy.

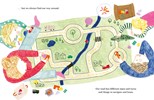

The consistent motif that defines the book is Alfie’s curiosity and love, framed by the famous fruit comparisons used to measure a baby-on-the-way. Someone, probably his devoted parents, have explained the baby’s growth to Alfie, and he is constantly adjusting his expectations. The endpapers prepare us with big, splashy examples of children’s artwork. Fruit is a great subject when you are learning to draw. We enter Alfie’s kitchen, where his bearded and apron-wearing dad is cooking, while his Mom patiently explains that a baby is growing inside her. Alfie’s wide-eyed expression registers surprise, perhaps disbelief.

You know Alfie’s parents, or at least you have met them or seen them in our neighborhood. They are real people, Mom in her green maternity overalls and Dad holding an ultrasound image to show Alfie who is soon to arrive. Alfie is excited to follow the fruit comparison. He is even wearing a tee shirt covered with bright red cherries as he notes his own height, and learns that the unborn sibling, at 12 weeks, is “as big as a perfect plum” It helps to be concrete when providing children with explanations, especially for events with monumental consequences.

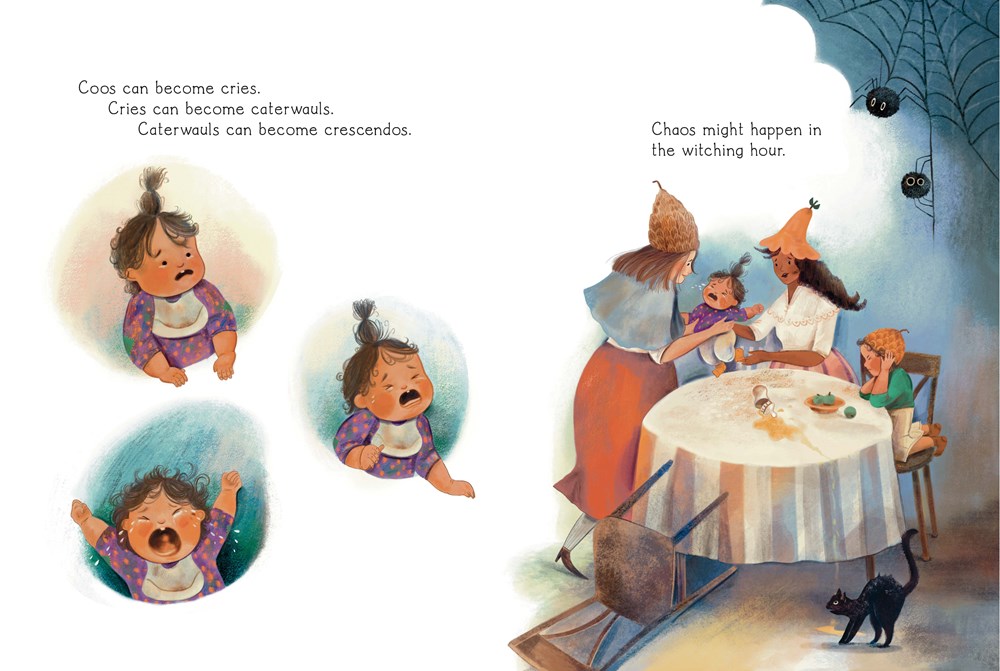

There is a fine line between emotion and sentimentality; Hutchings and Lo succeed in evoking a strong response without veering into patronizing territory. When Alife lies against his mother’s belly and feels the baby kick, he interprets this prenatal action as a sign of love, reminding the now mango-sized creature that his older brother is full of love, as well. Alfie communicates essential information to his sibling, including the fact that sometimes fear is part of life. When his dog is frightened of thunderstorms, Alfie hugs him.. This statement is not random; he intuits how vulnerable this future baby, now the size of a mere cauliflower, might feel when he joins their family.

At Alfie’s fourth birthday party, the pictures highlight a lovely bit of formality, with his mother now wearing a black and white polka-dotted dress accented by a pearl necklace. Dad takes a photo portrait of the scene. If you are a parent, I know you may be thinking that Alfie doesn’t actually know what to expect. The addition of a baby is not, at least at first, going to be unmitigated joy for him. It will be difficult. Again, there is an allusion to past and future feelings. Alfie has painted a rainbow for the baby, but he ran out of the yellow needed to complete his creation. “That’s what the crying was about.” Maybe. He is upset enough to need a reassuring embrace from his father. His mother is now really large, but still almost beatifically calm.

The book ends, not with the typical picture of a newborn, but with Alfie looking into the crib that his father has carefully assembled. The inside of the dustcover is a prenatal growth chart measured by pictures of produce. I will summarize by returning to Babar, because the stunning visual quality of this book elevates it way above the level of handy didactic works on the same theme: “Truly it is not easy to bring up a family…But how nice the babies are! I wouldn’t know how to get along without them any more.” Words to live by, for Alfie and his growing family.