The Newest Gnome – written and illustrated by Lauren Soloy

Tundra Books, 2025

The Pocket is where the gnomes live, in Lauren Soloy’s remarkable universe of small creatures dedicated to choosing hats, telling stories, and generally explaining and appreciating the world. I was impressed with the first gnome book, The Hidden World of Gnomes, and I’m thrilled that Soloy and Tundra believed in them, and that they merited a second look (I’m also a fan of Soloy’s other work, as you can see here and here and here). Although the gnome books are rooted in tradition and folklore, they are also new and singular.

When the book begins, the existing gnomes, including Cob Tiggy, Twiggy Dell, Minoletta, and Beatrix Nut, are about to welcome a newcomer to the Pocket. These creatures, whose names evoke both Beatrix Potter and a kind of cosmopolitan flare (Minoletta, Hotchi-Mossy), need to meet in their mushroom circle to discuss the latest Pocket resident. When Grolly Maru arrives, they sense the need for reassurance, similar to Winnie the Pooh’s helpful and sustaining words: “Everything will be all right.”

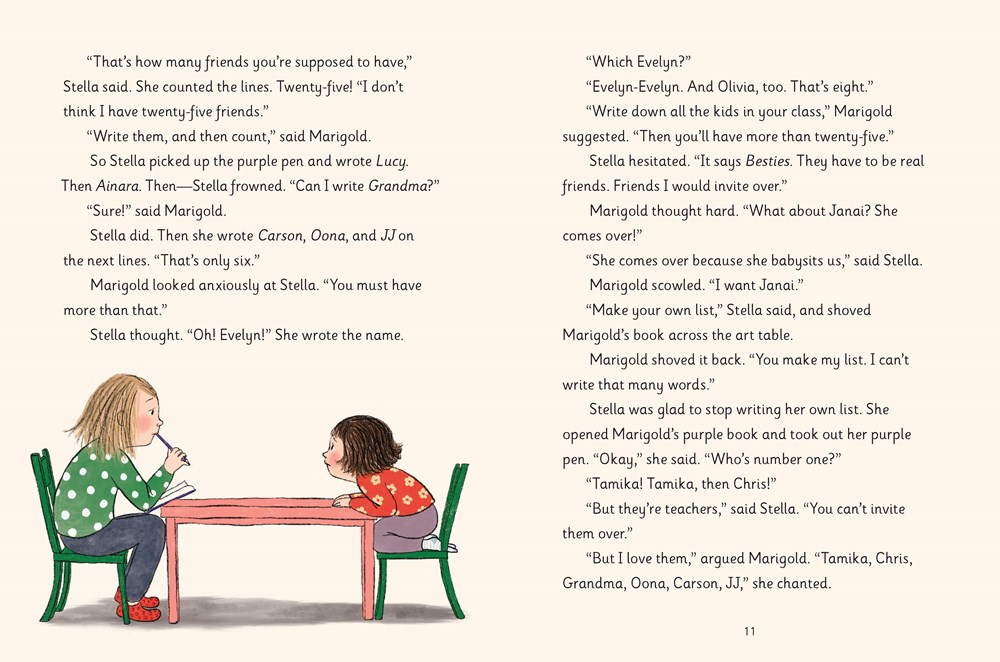

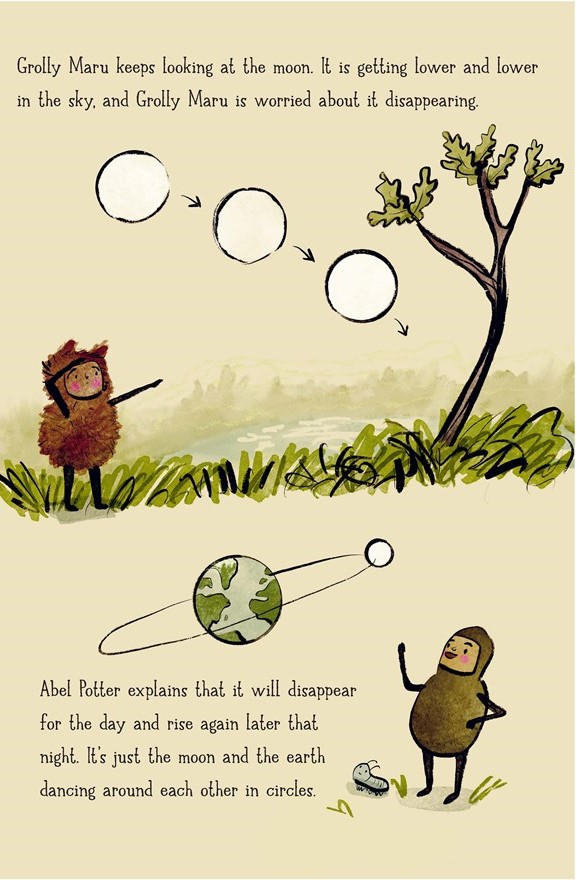

After a good night’s sleep under the mushrooms, the gnomes will be prepared to teach Grolly Maru essential skills. As in Babar’s Celesteville, every inhabitant has a specific job and role to play. When Grolly Maru expresses concern that the changing moon may eventually disappear, does this reflect and anxious personality, or just a basic lack of familiarity with the environment? It’s up to the reader to decide, but since Abel Potter shows Grolly Maru other round and spherical items from nature, it doesn’t matter.

The pictures feature gnomes interacting with one another, along with close-ups of objects that fill their lives: dandelions, yarrow, marbles, ants, and suggested exercises. There is a recipe for Bonnie Plum’s baked apple with blackberries, which, considering the scale of gnome to ingredients requires both hardware and strength. The gnomes are artisans, designing grass baskets: “It’s not as easy as it looks!” (Who would expect it to be easy?). Their overarching purpose is constant fidelity to the idea that each individual is unique, but that we are all part of something greater. Lauren Soloy’s artistic vision is fully realized, in a universe of beauty and comfort, populated by small beings with great wisdom.