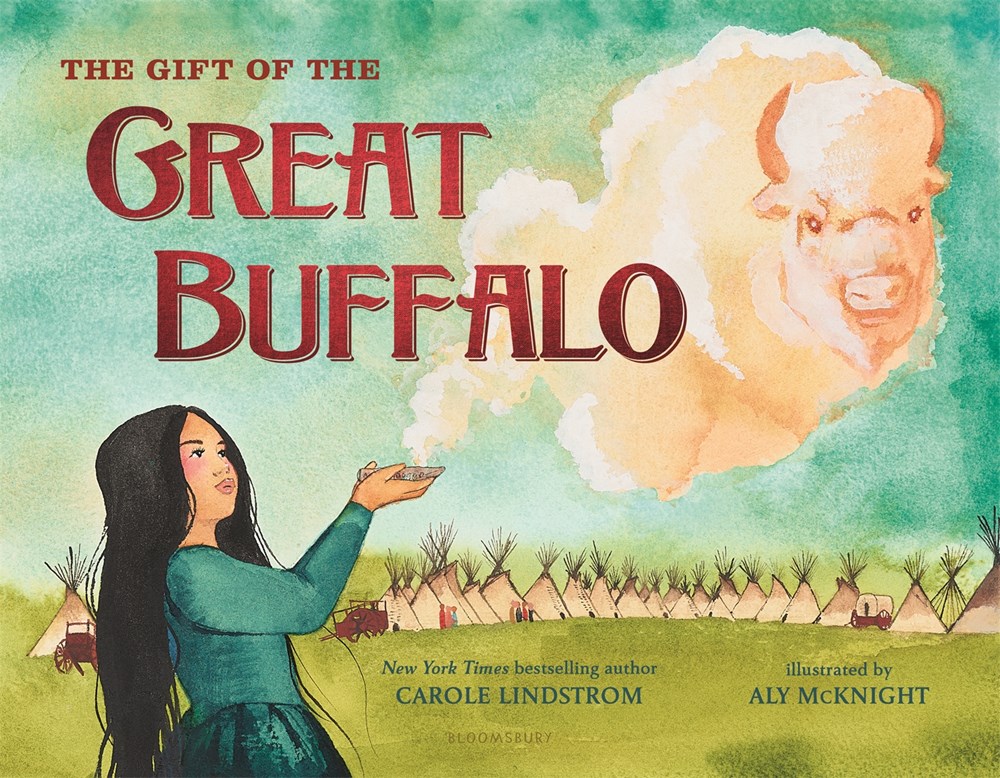

The Gift of the Great Buffalo – written by Carole Lindstrom, illustrated by Aly McKnight

Bloomsbury Children’s Books

Rose lives on the prairies, in a Métis-Obijwe indigenous community. Preparing for the buffalo hunt that will sustain her people, she is eager to actively take part. This elegant picture book takes place in the 1880s, and, like Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie series, Rose’s dwelling is small and homemade. However, as author Carole Lindstrom explains in her detailed “Author’s Note,” she was motivated to tell Rose’s story by her own sense of distance from Wilder’s accounts. The Gift of the Buffalo offers the perspective of the Native Americans who are a shadowy and distorted presence in Little House. Lindstrom and the artist, Aly McKnight have not created a rebuke, but rather, an alternative and illuminating vision.

I have written about the complexity of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s works (see here and here and here and here and here), which, along with racism, include a great deal of ambiguity about how a young girl interprets the conflicting messages of her parents and community about the people whose land they have appropriated. The Gift of the Buffalo would stand alone for its excellence, even without the essential commentary that Lindstrom and Ally McKnight offer about the reality of an autonomous world, which is not merely a frustrating background for the story of Wilder’s pioneers. Rose is an intelligent and perceptive child. When her father discourages her from accompanying him on the buffalo hunt, insisting that “that’s no place for you. Besides, Ma needs you more,” she cannot accept his restriction.

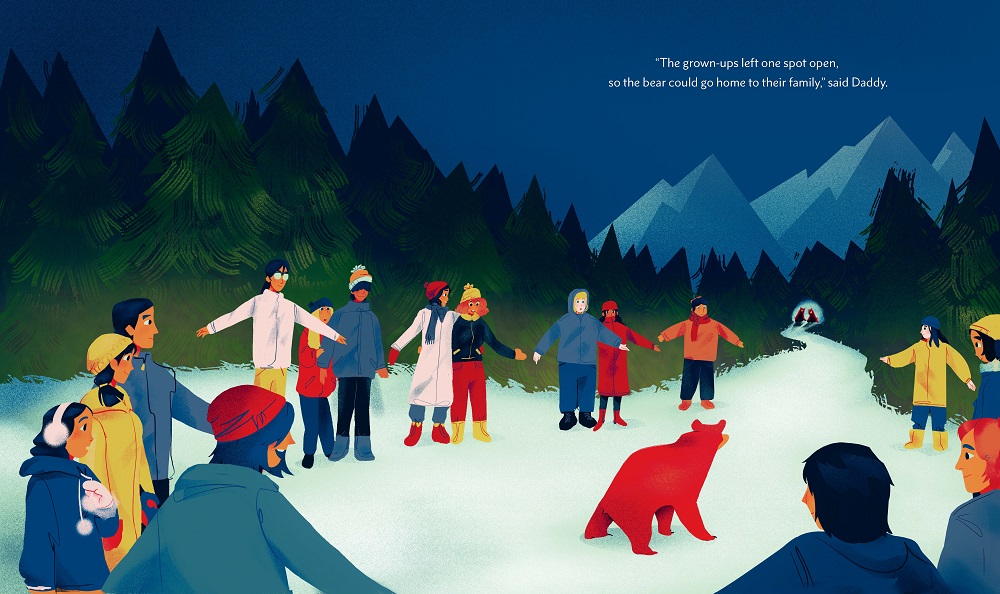

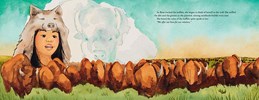

Rose’s decision to defy her father is not based principally on her individual needs, although there is an implicit statement about the independence of a young girl. She is deeply concerned about her family and friends. Lying in bed next to her oshiimeyan (younger sister), both of them enveloped in buffalo robes, she is excited about the hunt. When she later hears adults express concern about their lack of success, she knows that she will need to step forward. Pragmatism is connected to spirituality; Rose will communicate directly with the spirit of the animals that, in the Métis consciousness, will give their lives to sustain their fellow beings.

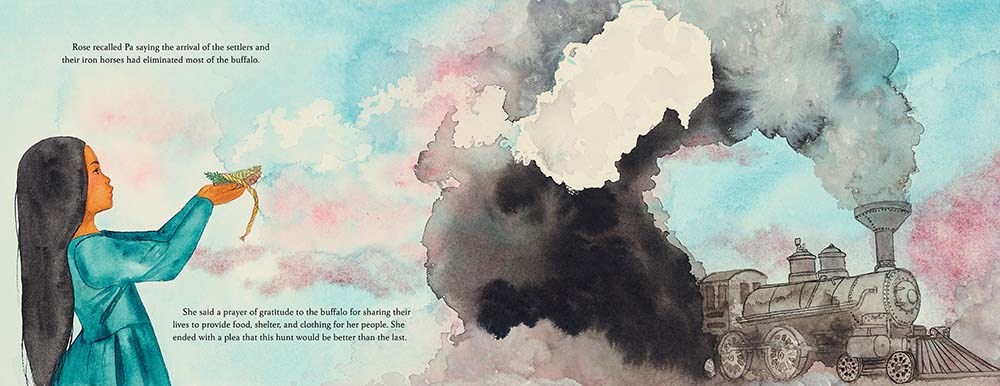

The watercolor and graphite illustrations are stunningly beautiful. Earth and jewel colors, expressive faces, and alternating dark and light, frame realistic depictions infused with metaphor. Rose, in a blue dress that complements the lighter blue of the sky, offers up a prayer of gratitude, in advance, expecting that the buffalo will “provide food, shelter, and clothing for her people.” Her father sometimes wears a wolf skin when hunting, and Rose assumes the mantle of his authority by putting on the special garment and identifying with the wolf. This ritual enables her to hear the buffalo assure her that her efforts will be productive: “We offer our lives for our relatives.” This evidence of mutual connection contrasts sharply with the exploitation of settlers, who had exhausted the supply of animals, even hunting for sport.

After the hunt, Rose’s father gently admonishes her. She had located the buffalo, but only by breaking his rule. His suggestion that she might, in the future, accompany him on a hunt, shows recognition of her needs as well as those of the tribe. Readers will find familiar elements in Rose’s story of independence and growth, as well as an invitation to learn about a different house, family, and world.