Welcome to the Penguin Cruise: A Seek-and-Find Adventure – written and illustrated by Haluka Nohana

Chronicle Books, 2025

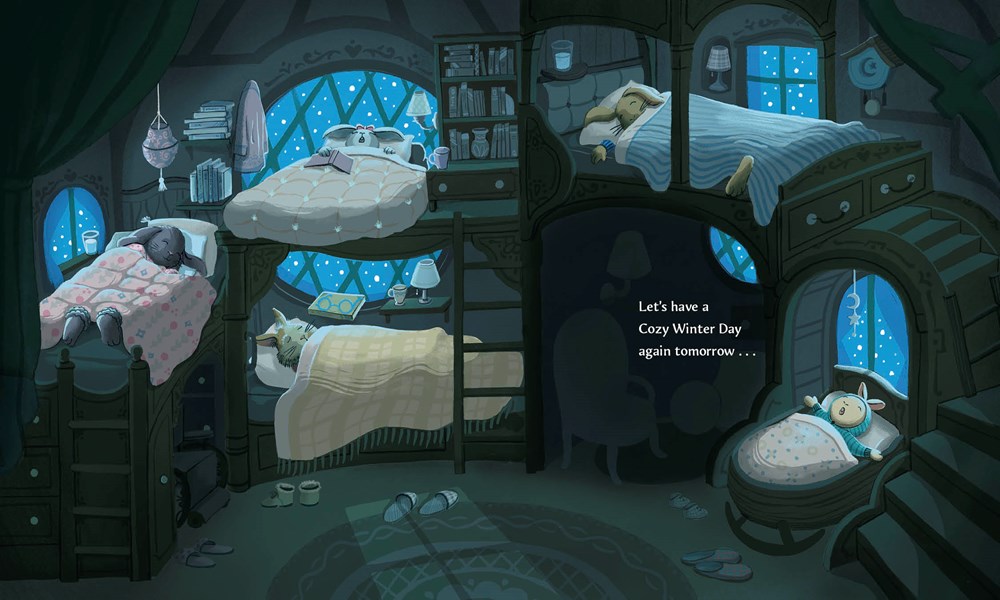

These penguins do not even all dress alike. They are mechanics, explorers, athletes, musicians, and artists. Aboard their adventurous cruise, they have as many different professions as the residents of Celesteville in Babar the King. When the book begins, Chibi the Penguin and his family are about to board ship for a cruise. The magnificent vessel, which opens from the center as a four-page spread, contains every activity possible enroute to a mysterious location. Cutaway images of the ship invite readers inside, as in Richard Scarry’s works or the European wimmelbooks that inspired him and continue to be fascinating to children (see more here).

Look-and-find is a subcategory of these books. Searching for objects and people is entertaining and educational, but the pictures alone just reflect a view of the world as crowded with endlessly interesting experiences. The penguin theme adds a specific dimension. Wearing a variety of outfits over their simple black and white, these creatures read books, watch movies, prepare and eat meals, and pilot a massive ship.

Then the essential Gold Mermaid statuette disappears, offering Haluka Nohana the opportunity to quote Walt Whitman as the Oceano Penguino’s officer is alerted to her disappearance: “O Captain! My Captain!” A stop on Turtle Isle allows passengers to relax on terra firma, and also to search for a mermaid. Subtle overlapping among the pictures, with small differences, calls for careful reading and viewing. The film-watching penguins change in number and position an empty bed has sleeping occupants, the captain is assisted by a crew member. The Fire Dragon adds a magical touch as he interacts with passengers. What exactly is he doing on the cruise?

At the end of the book there is an additional inventory of items to find. But even once located, trips on the Oceano Penguino have not been exhausted. Leaping dolphins, penguin dance parties, and the elusive Phantom Thief Lupenguin merit many turns of the page, with or without mermaids.