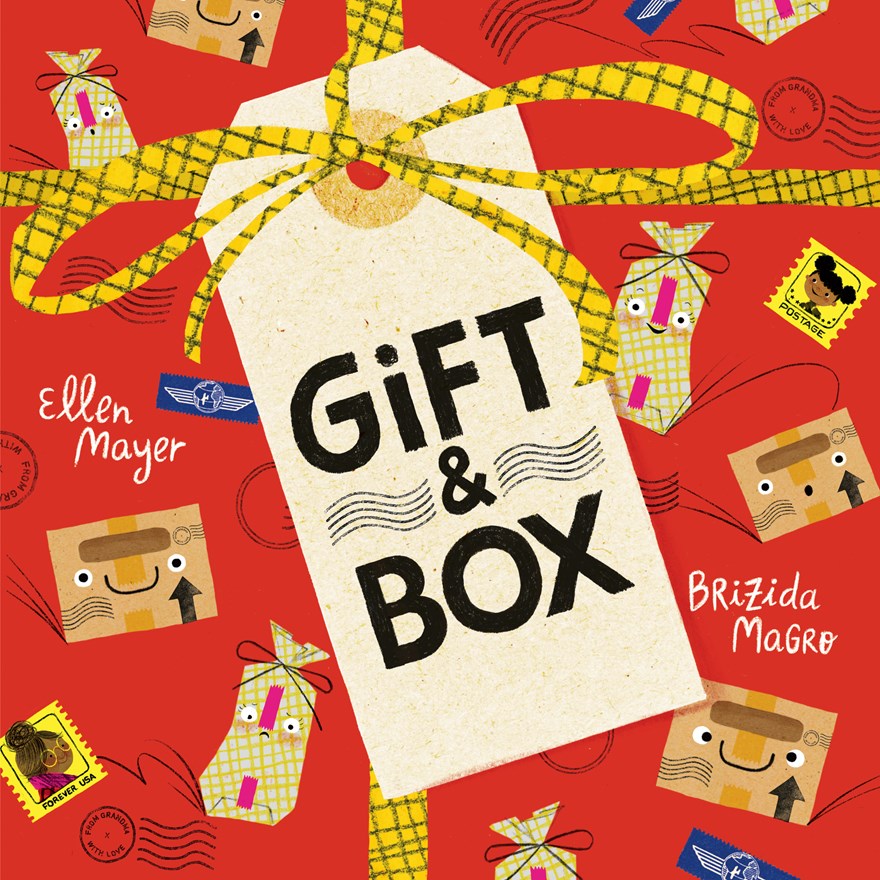

Gift & Box – written by Ellen Mayer, illustrated by Brizida Magro

Alfred A. Knopf, 2023

It’s good to know that there are still authors and illustrators celebrating the postal system. Ellen Mayer and Brizida Magro’s wonderful addition to this genre opens with endpapers that display visually specific examples of snail mail. There are some real stamps, invented ones, postmarks, and snippets of correspondence. In the tradition spanning Tibor Gergely’s Seven Little Postman, Rosemary Wells’s works, and Zoey Abbott’s I Do Not Like Yolanda, Gift & Box describes the unique experience of sending a letter or package via USPS.

Two personified objects, a gift and a box, meet and employ their complementary skills to make someone happy. The pictures are composed artfully. The love between a grandparent and grandchild is also at the center of the story. (Regular readers of this blog know that picturebooks about grandmothers are one of my favorite subgenres; see here and here and here and here and here and here.) We see Grandma happily tying a bow on a bag decorated with lovely eyes and a friendly smile. A scissor, string, tags, and scraps occupy the bottom of the page, with white space in between. There are also images of real stamps. They are real not only in the sense of legitimate, but they are from the era when stamps were actually engraved, on woven paper in a range of beautiful colors. These three appear to be deep green, carmine, and bright blue-green. (If you look closely, the one cent “Industry and Agriculture: For Defense” stamp is reproduced with inverted lettering. This might be a deliberate choice.)

The gift and box work together. Mayer emphasizes the cooperative aspect of their task: “Gift’s purpose was to delight. Box’s purpose was to protect.” Their long journey may be important, but it is also tedious at times, involving a lot of waiting. There is even some danger involved. There are collage elements in many of the pictures, reflecting the artist’s use of several media. (“The illustrations were created using rolled printmaking inks, crayons, handmade stamps, and paper collage, then assembled digitally.) Busy city streets are a context for the gift’s voyage, with earth and jewel-toned vehicles passing apartment buildings. The human figures have an Ed Emberley-style simplicity.

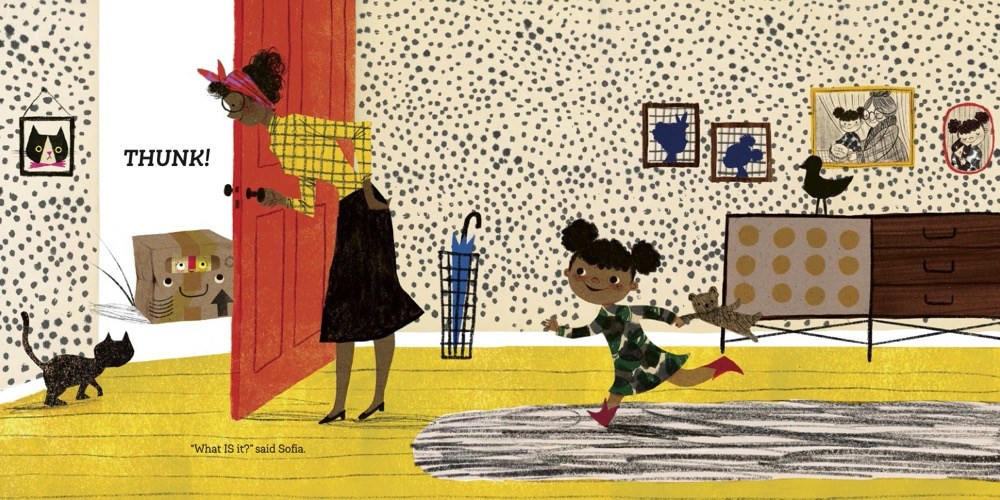

Eventually, the package arrives. A little girl, Sofia, asks her mother about the loud noise outside the door. Her mother opens the door expectantly. Their home is filled with mid-century design: a streamlined bureau, a bright blue umbrella in a wire stand. The pictures on the wall include one of Sofia and Grandma. Sofia is delighted with her gift, but is reluctant to part with the box. Readers have been prepared throughout the story for the moment when gift and box, having accomplished their goal, will part. Instead, Sofia’s energy and imagination transform them into something new.