Maddi’s Fridge – written by Lois Brandt, illustrated by Vin Vogel

Flashlight Press, 2014 (paperback edition, 2022. Reading app available:

https://apps.apple.com/us/app/maddis-fridge/id6748969593)

Thanksgiving is associated with families sharing a plentiful amount of food, but not all Americans have access to this custom. Freedom from hunger is a human right. Historically, it has been an American right, even if this ideal has not always been realized. Norman Rockwell’s iconic paintings depict the Four Freedoms that President Roosevelt had a promoted during World War II as a reminder of the war’s purpose. Maddi’s Fridge is a non-ideological picture book for children.

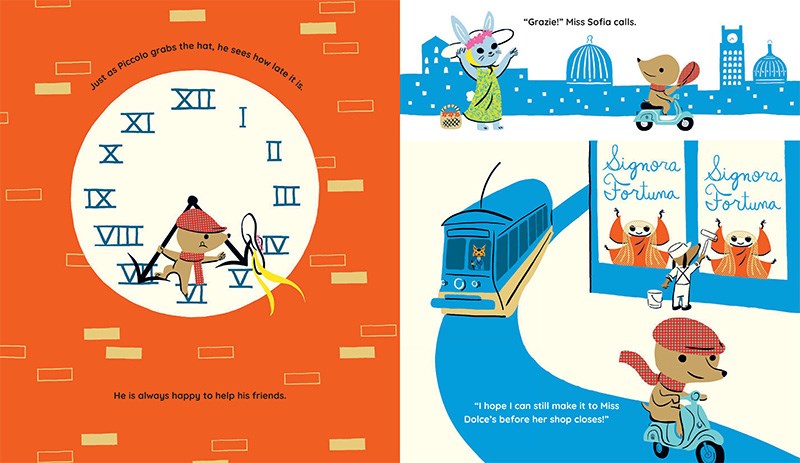

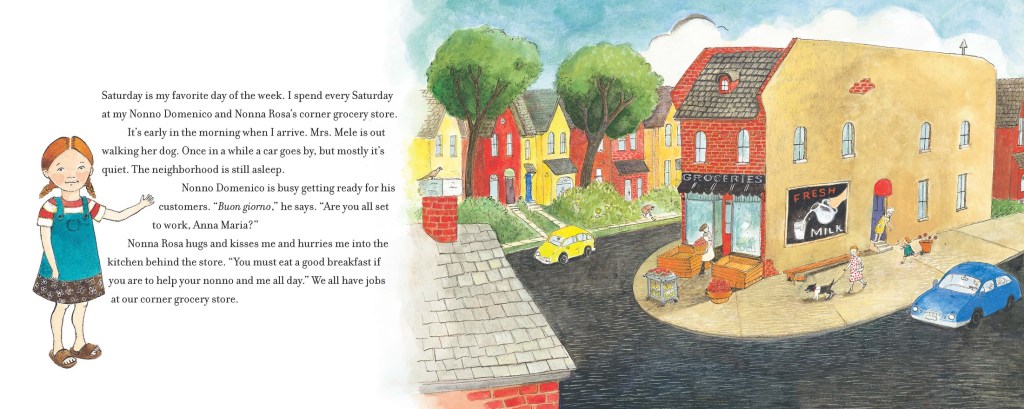

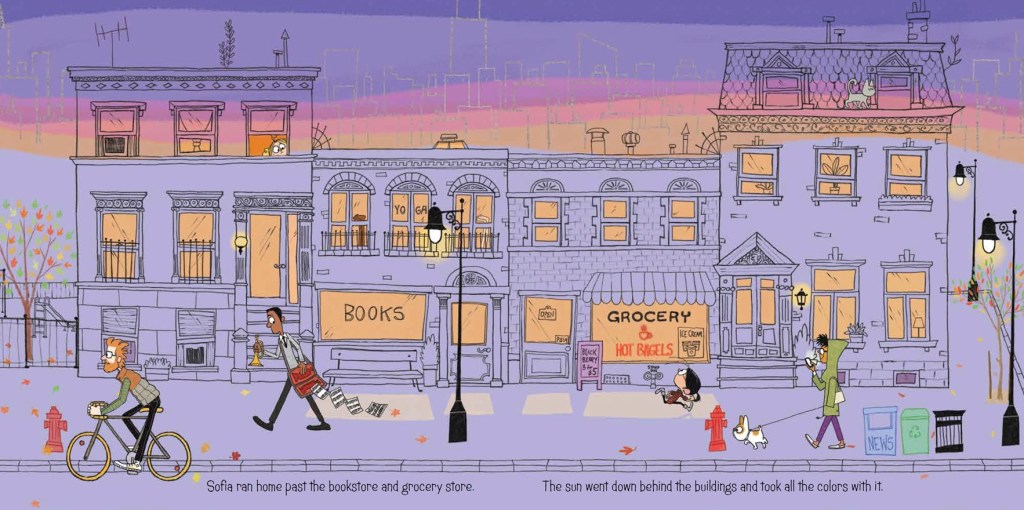

It does not discuss the social and economic programs needed to combat income inequality; that is not its purpose. Lois Brandt and Vin Vogel present the problem of hunger through the friendship of two girls, Sofia and Maddi. Sofia has always assumed that her well-stocked refrigerator is the norm. When she learns that her friend’s is virtually empty, Sofia needs to help her friend without betraying a secret.

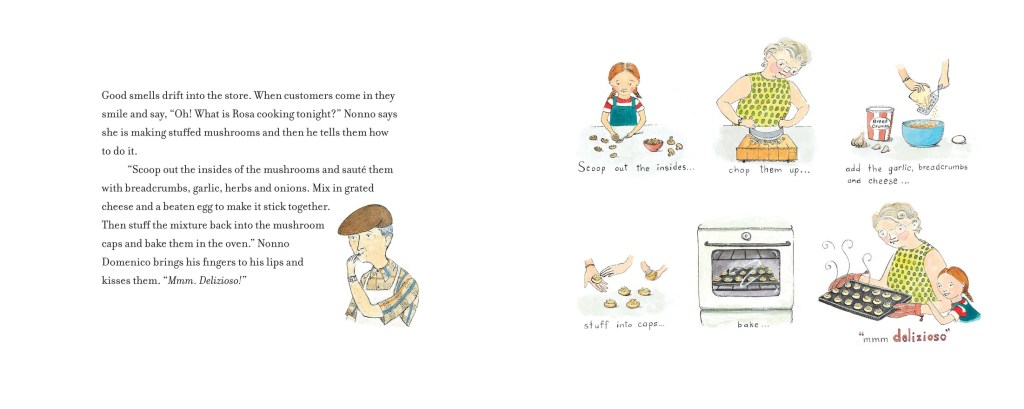

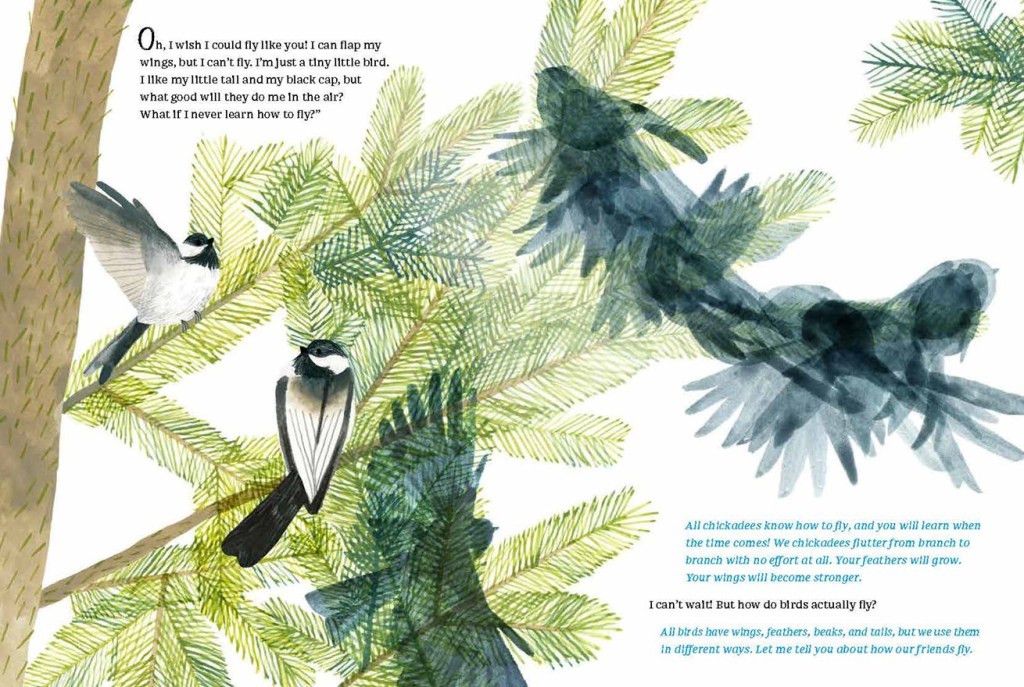

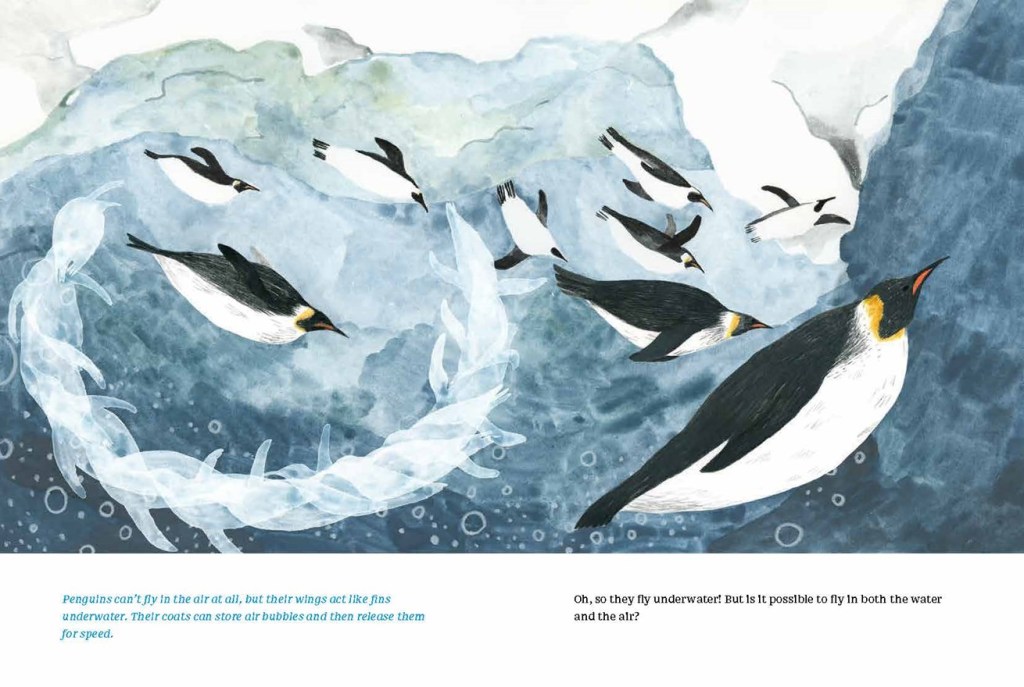

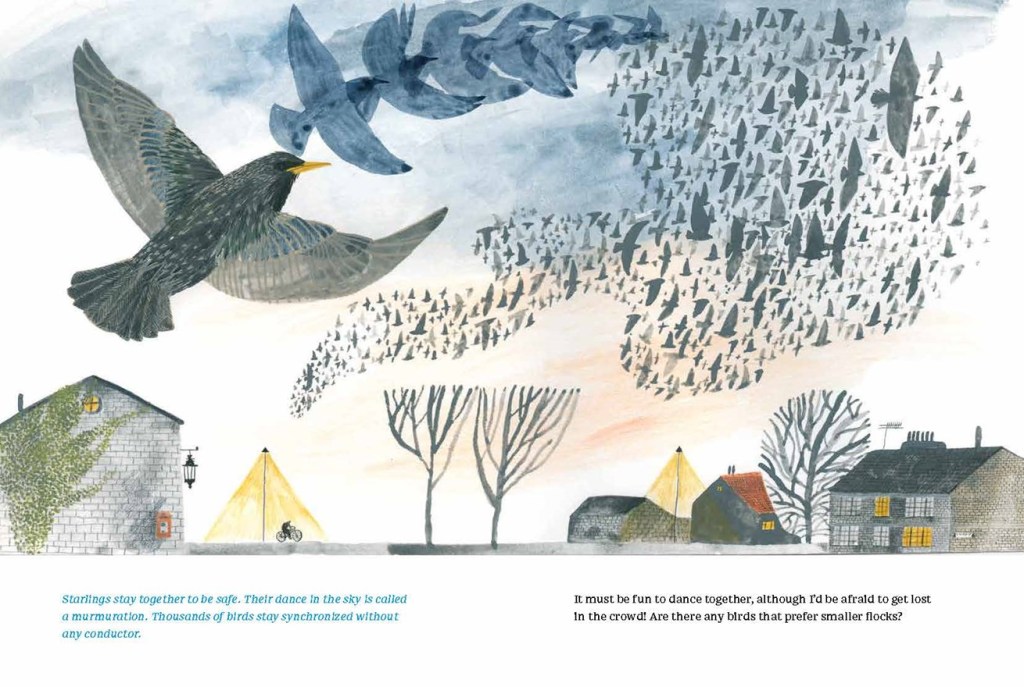

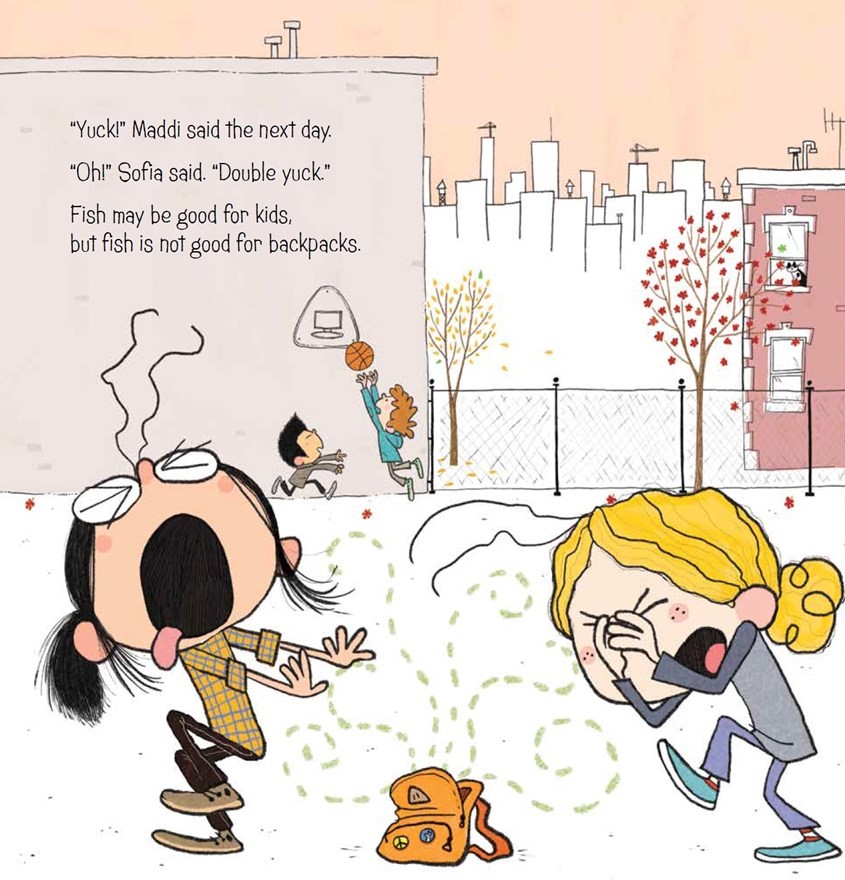

Vogel’s illustrations are understated and appealing. They convey a sense of community, even a modern version of Rockwell’s, as well as a touch of mid-twentieth century animation.

Sofia’s family is well-fed, with the inventory of her refrigerator even including dog food. Brandt enumerates each item for human consumption: chicken, yogurt, cheese, carrots, bread. In contrast, her friend Maddi’s refrigerator has barely enough to sustain her and her younger brother. Brandt and Vogel show, in words and images, the asymmetry of the situation without elaborating on its cause. Instead, Sofia’s dilemma is central to the story. How can she help Maddi? Bringing foods for the two friends to share as they play outside will not address the problem.

Adults reading with their children may anticipate Sofia’s decision, but children will not necessarily predict the outcome. Maddi’s Fridge presents an opportunity to discuss why breaking a promise of secrecy may be not only permissible, but crucial. The book’s afterword provides further suggestions for filling empty fridges, on an individual and communal level. The book’s relevance today is a sad statement about the refusal to ensure that all children are cared for, but it at least represents an intelligent and sensitive way to shed light on the problem.