Lights at Night – written by Tasha Hilderman, illustrated by Maggie Zeng

Tundra Books 2025

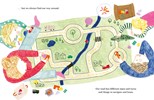

There are two families observing the rhythms of the year in Lights at Night. One is human and the other canine, specifically foxes. Dream-like images with changing shades of color include realistic details, both natural and cultural. Children experience the wonder, but also the reassurance, of the four seasons and their special features, from football in autumn to storms in spring. While the fox family does not kindle holiday lights around the time of the winter solstice, they also appear to respond to the changes. Tasha Hilderman’s soothing poetic text complements Maggie Zeng’s visual immersion in the excitement of one year. Children find joy, not boredom, in the repetition of familiar events.

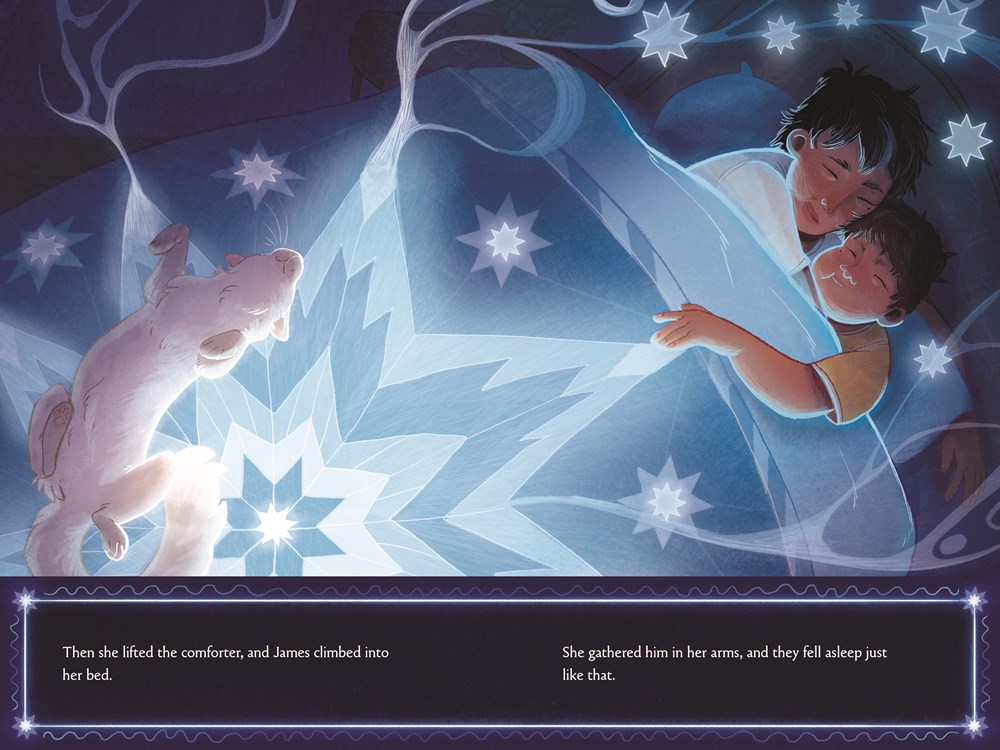

A powerful storm is just unsettling enough to make the shelter of home more of a comfort. Crayon drawn strikes of lightening emanate from a house, enclosed in a photograph, and also cross its border. Inside, a strong of lights and beds configured as tents add the sense of drama that children like. Note the plush fox in a small sleeping bag. The fox family lacks the domestic props, but is just as attuned to the environmental changes. Of course, animals’ lives are more closely defined by the seasons. In spring, “new babies arrive with the stars.”

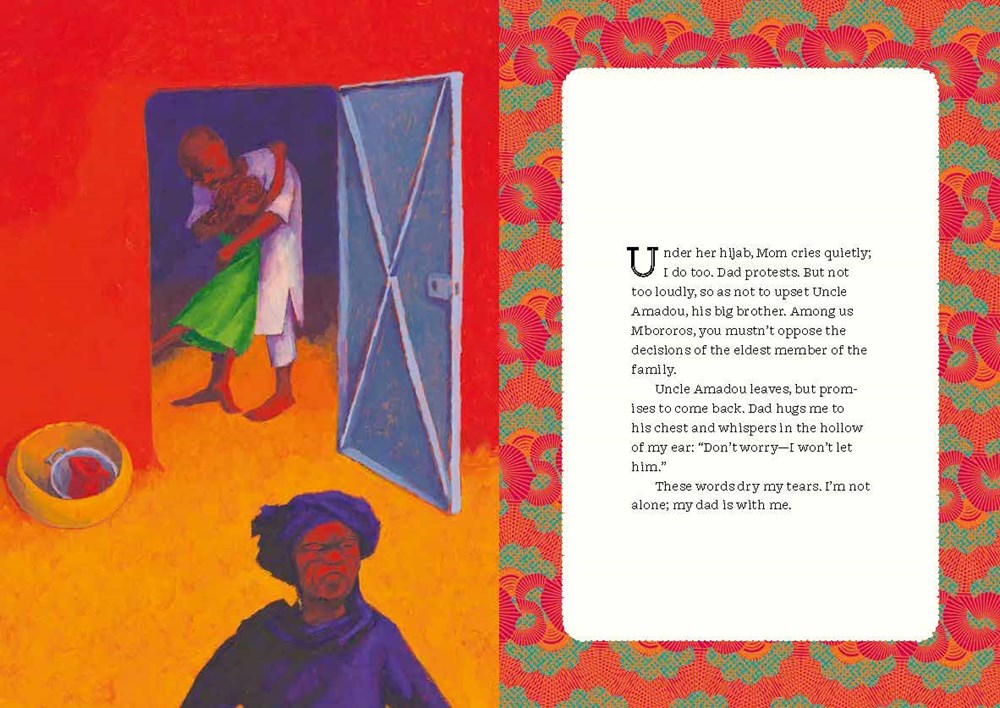

Campfires come in summer; riding the bus to school and harvesting wheat are tied to autumn. One of my favorite images in the book is a natural and unobtrusive celebration of multicultural holidays. Christmas trees, Diwali lights, a Muslim family welcoming visitors, and a Kwanzaa lamp grace the neighborhood, along with a Jewish family’s observance of Chanukah. If you look closely, you will see that the correctly depicted nine branch chanukiyah (menorah) has its candle farthest to the left partly obscured by the window frame. This is not an error, just a small visual element lending authenticity to the way in which someone placed the lights, which must be visible from the outside.

At the end of the book, the two children share an album and a box of crayons. The volume is open to the photo with lightning, enhanced by the children’s artwork. The actual fox looks up the moon.