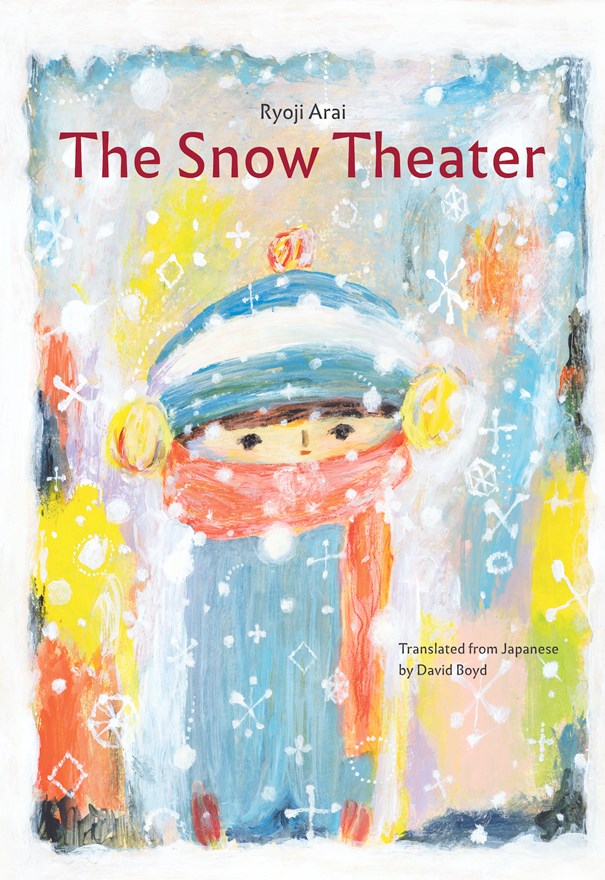

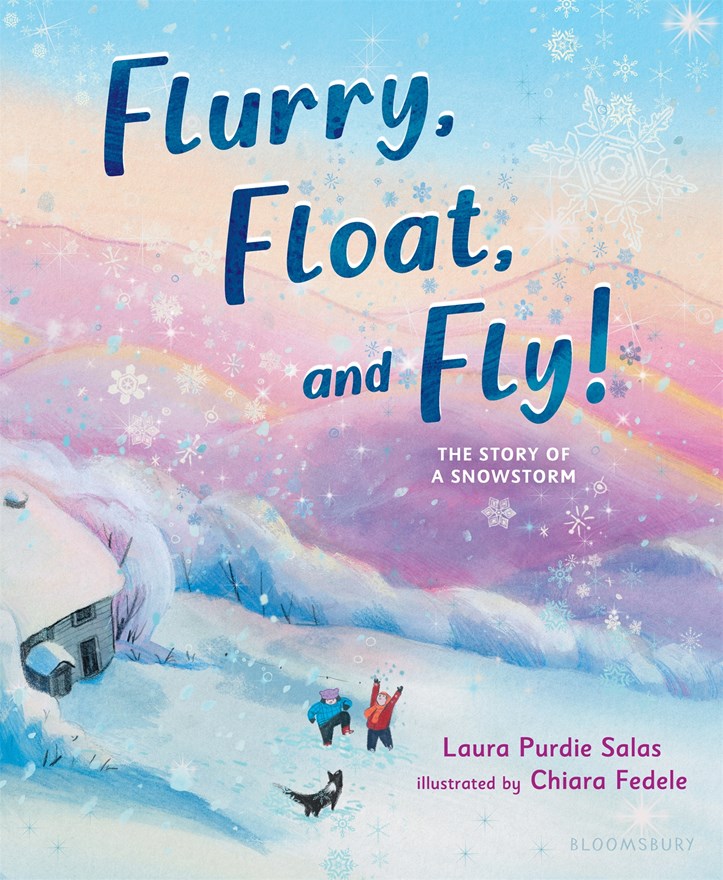

Flurry, Float, and Fly!:The Story of a Snowstorm – written by Laura Purdie Salas, illustrated by Chiara Fedele

Bloomsbury Children’s Books, 2025

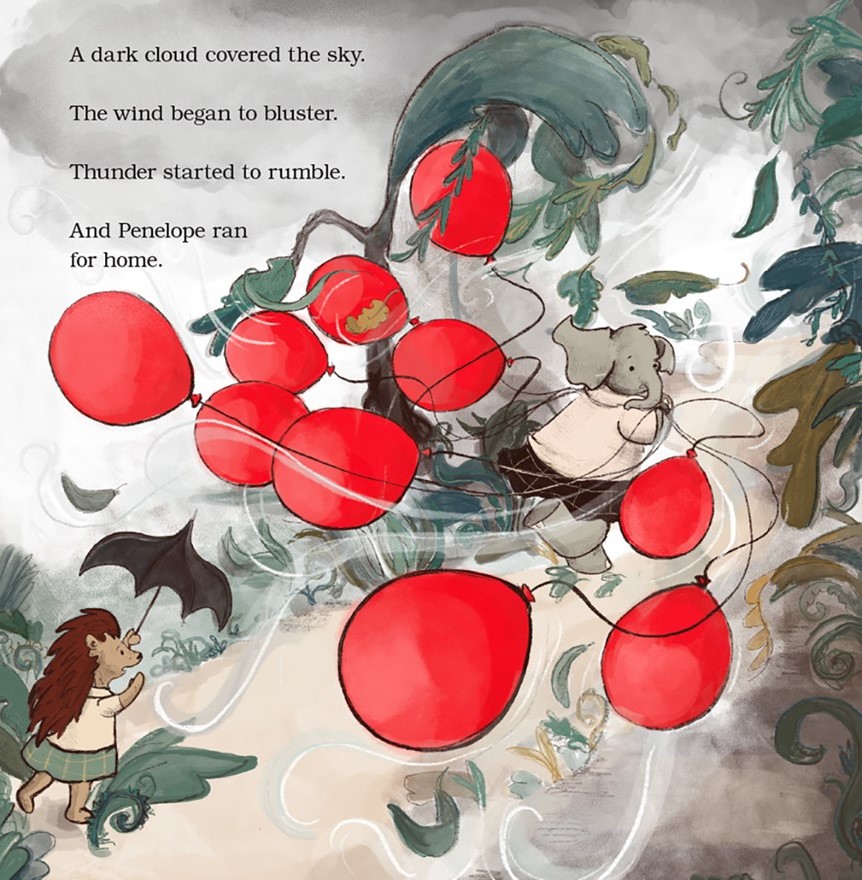

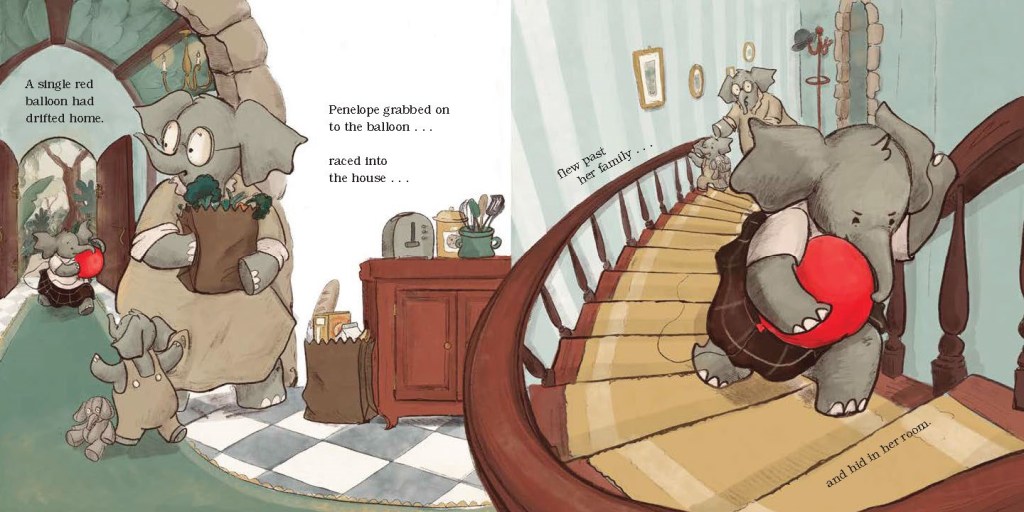

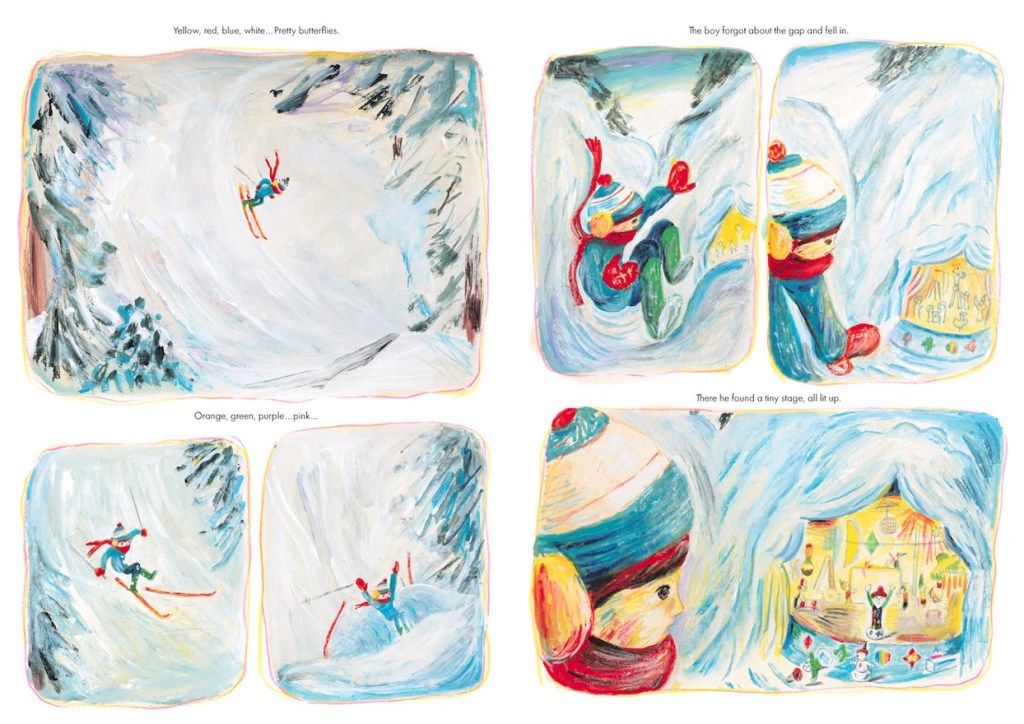

There are STEM picture books that integrate the informational content into a story, and others that place aesthetic appeal at the center, adding the scientific context in the backmatter. The text of Flurry, Float, and Fly is full of momentum and joy, while the pictures, rendered in watercolor, gouache, and pencils with digital editing, are both bold and delicate. Jewel tones are placed against pastel or muted shades. Snow itself is a precise phenomenon, explained in detail in a separate section, “The Science of Snow.” The unparalleled wonder of welcoming a snowstorm emerges from every page. Regular readers of this blog know that snow books are one of my favorite genres (my most recent one before today includes links to the earlier ones).

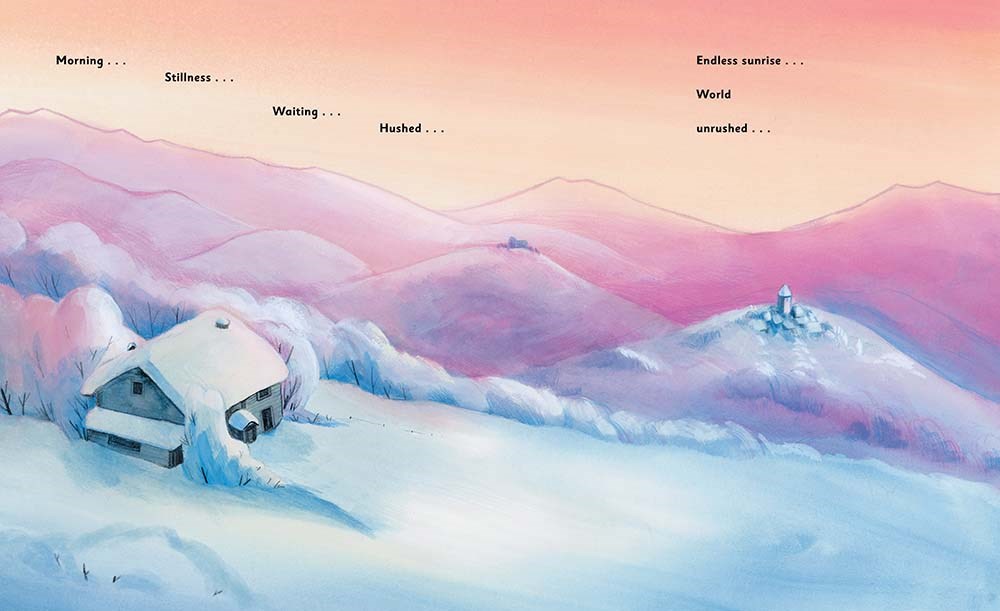

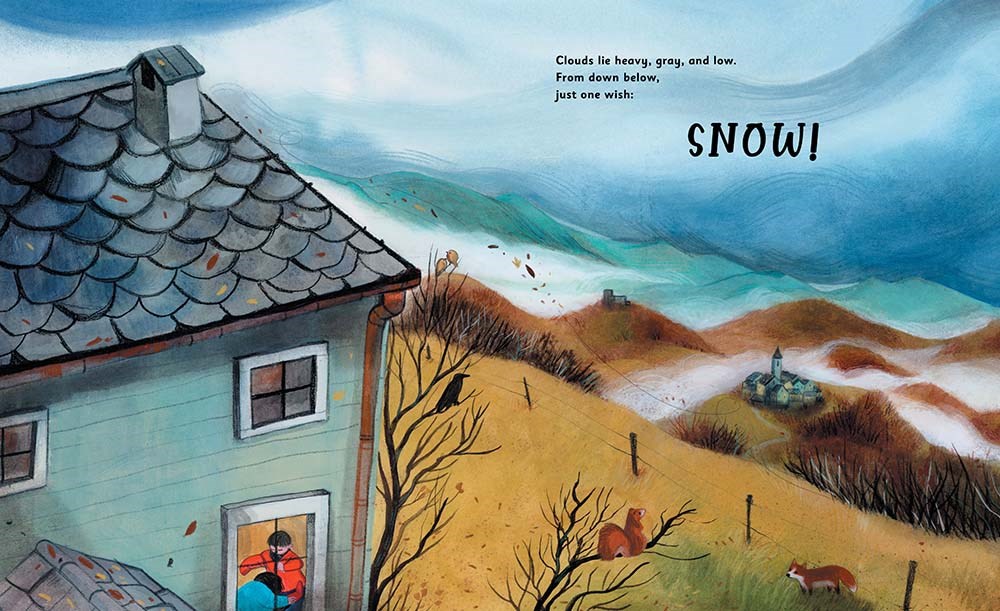

Laura Purdie Salas’s text and Chiara Fedele’s pictures are composed to interact perfectly (I reviewed Salas’ book on thunderstorms here, and I have reviewed several books illustrated by Fedele—here and here and here–but this is their first joint effort I have seen). The bold black text is in a minimalist, poetic style. A house with a snow-covered roof in the foreground, other buildings in a distant background, and a blanket of white fill the bottom of a two-page spread. A pink and yellow horizon allows the words to speak quietly: Morning…Stillness…Waiting…Hushed.” Perspective supports the effect of comparing human activity to the expanse of nature. In one corner of a scene, two people are framed by the window of their house. In the center, a fox and a squirrel look up expectantly. In the distance, a town appears as if in miniature, while the blue and white sky appears ready to fulfill a wish for “SNOW!”

The words of the title actually first appear as a disappointment. Two children are ready with a sled, but they are sitting and standing on a bed of leaves. Fedele’s use of color is dramatic within a quiet setting. One child wears a bright red coat. The girl sitting on the sled has red boots, a cobalt blue jacket and violet hat. The fox is red, as are two small birds sitting on the bare branch of a tree. “No snow to flurry, float, and fly” is about to be replaced by its opposite. Another picture reverses the position of house and outdoors, with a family sitting in the window on the right of the scene, and the “merging crystals” beginning to form and fill the sky on the right. The interior of the family’s room is shimmering gold and the green of their sweaters recalls the distant season of spring more than the forest green of winter.

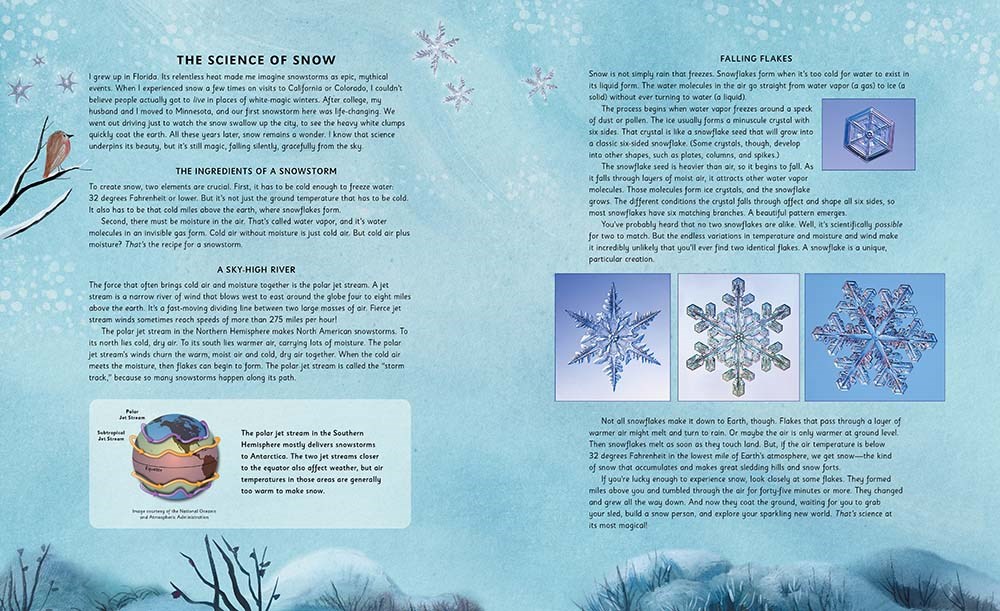

There are allusions to the fact that snow is not formed out of poetry throughout the book, as in the reminder that “Water vapor clings to dust,/begins to form a slushy crust.” The carefully presented information at the book’s conclusion illuminates the intersection between different experiences. “Columns don’t have arms or branches. Instead, they’re simply tubes with six sides, like old school pencils.” Those old pencils might even be multicolored, aligning the complexity of a snowflake’s structure with the sheer excitement of a storm.