Penelope’s Balloons – written and illustrated by Brooke Bourgeois

Union Square Kids, 2024

Children can become attached to unexpected objects. Some, like balloons, have a limited life span. In Penelope’s Balloons by Brooke Bourgeois, a young elephant who is “quiet…bright,” and “a bit particular,” cannot let go of ten red balloons, either literally or figuratively. She is happy lying on her back and watching them suspended in the air, but also keeps them close while eating or diving.

From the beginning of the story, it seems evident that there will be both a problem and a message here. Penelope’s balloon obsession does not prevent her from socializing, In fact, she has many friends of different species. The balloons only make her more “perceptible” and popular, to choose another adjective that is alliterative with her name. The problem is the fragile nature of her favorite item. Her best friend, Piper, is a hedgehog; say no more. Allie is an alligator with sharp teeth. On the other hand, Gerry the giraffe is a good friend to have, her long neck offering some protection from potential piercing.

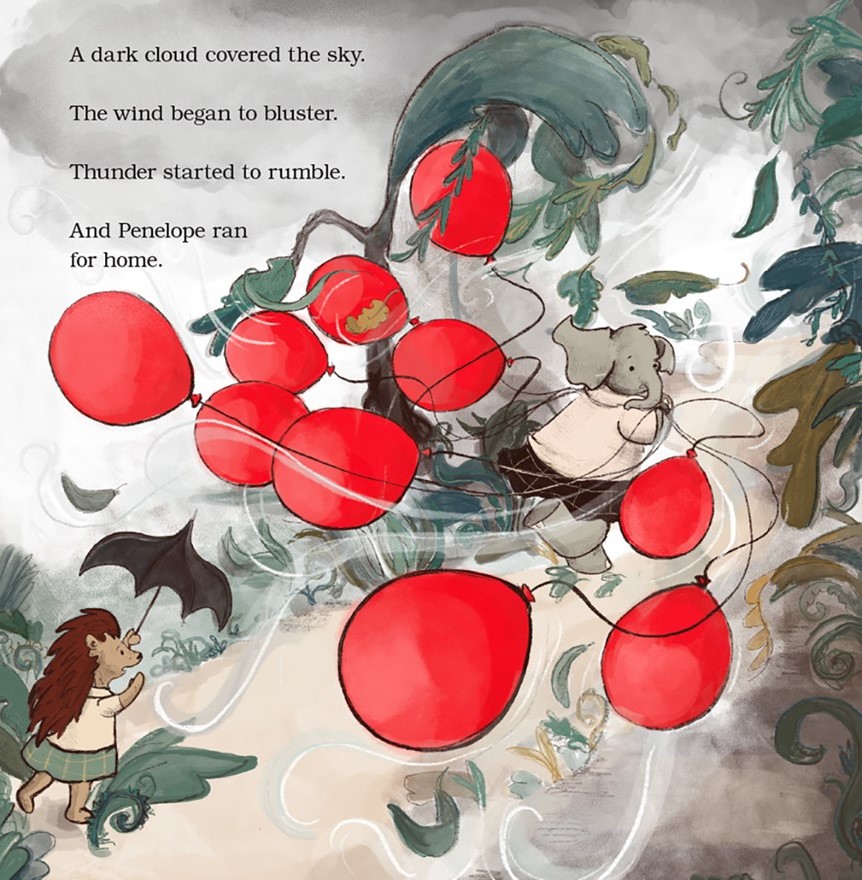

Eventually, Penelope learns the inevitable lesson about avoiding disaster. Sometimes you cannot. A thunderstorm does not have functional points, but it’s invisible winds can still destroy. Forlorn, Penelope shelters in the forest. She is alone. This picture has no bright red to contrast with the gray and green foliage. Even her friend Piper’s comforting words cannot erase Penelope’s grief. As Piper leads her across a thick branch serving as a bridge, the young elephant is hunched over, her ears falling like flaps over her face. All of a sudden, she seems old.

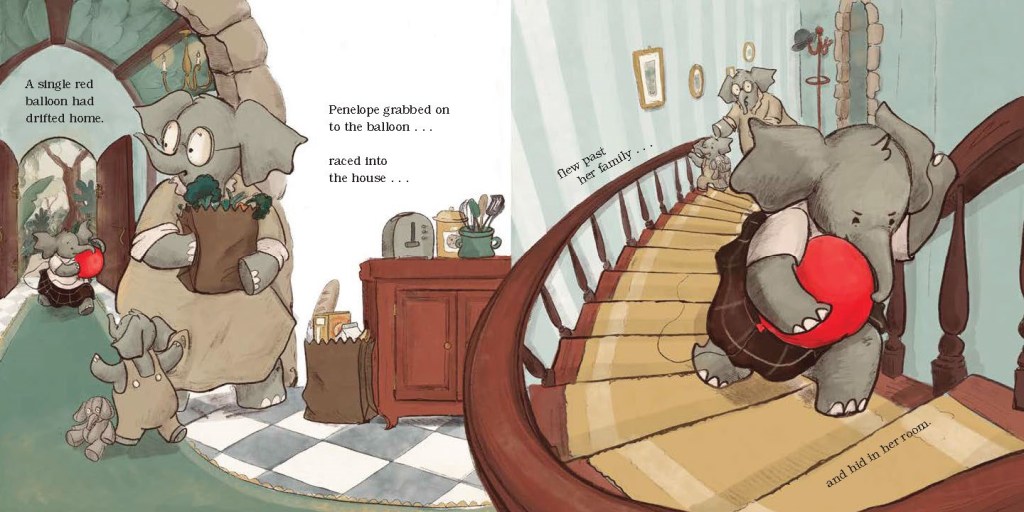

Arriving home, Penelope stands in front of the doors and rushes in. One balloon has survived and accompanied her. Now we meet her parents. Her mother seems almost confused, which is surprising. Surely her family is well-aware of her balloon problem. There is an expressive scene, viewed from the top of the staircase, of a determined Penelope racing her room. Her mother and younger sibling are small and helpless figures receding into the background.

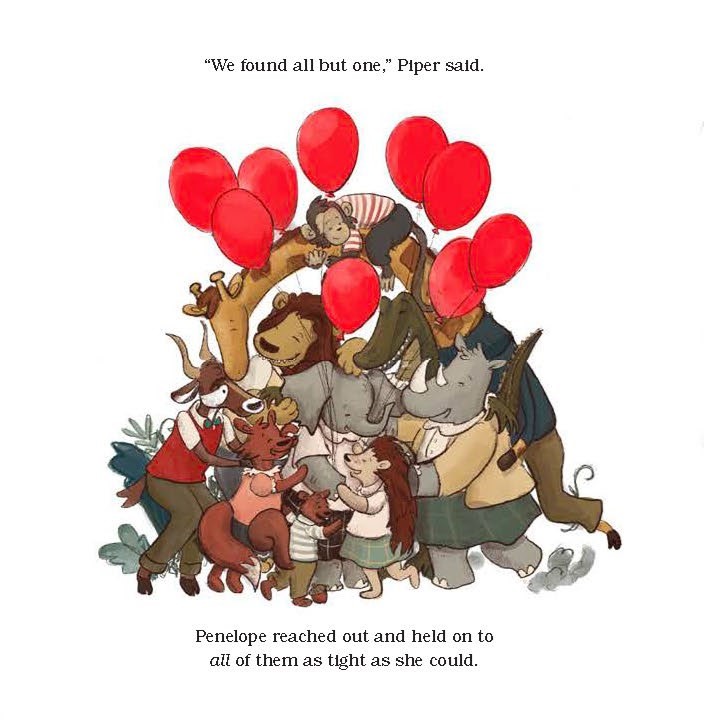

Penelope frantically sets to work creating an elaborate fort to protect the balloon. Her intense anxiety foreshadows the upcoming disaster, as well as the solution. Sometimes, with patience, things will work out. The likelihood of this scenario, with the other nine balloons all magically reappearing, seems like pure wish fulfillment (as in Claire Keane’s Love Is). However, Penelope decides that giving her balloons, or, by extension, any beloved, a little space, is the best way to keep them close. The author also suggests that Penelope’s strange attachment had actually been distancing her from her actual friends, “the sharp and spiky ones” who posed a threat to her happiness.

A word about Babar seems required. Any children’s book presenting anthropomorphized elephants seems, to some extent, an homage to Jean and Laurent de Brunhoff. Certainly, some of her animal friends include monkeys, rhinos, and other residents of Celesteville. (Although the rhinos are not bad guys here.) Penelope is certainly less sophisticated and cosmopolitan than Babar, but there is still a sweet reminder of how animals with human qualities offer a unique connection with children. There is more than one lesson in Penelope’s Balloons, and the book is well-worth sharing with them.