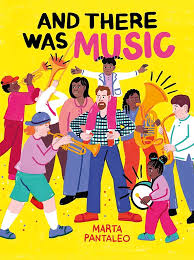

And There Was Music – written and illustrated by Marta Pantaleo, translated from the Italian by Debbie Bibo

Eerdmans Books for Young Readers, 2025

Sometimes children’s books address a question that may seem obvious. How can you explain the meaning of music, the way that people use it to communicate regardless of whether they share a language or a culture? Marta Pantaleo’s And There Was Music offers an answer through spare, poetic language, and bright imagery. Her answer is non-academic, not definitional. Instead, she approaches the subject through examples that are diverse enough to constitute a whole. Music is shared by everyone, arises from our senses, memories, and emotions, and utilizes different instruments, as well as our voices and bodies, to make itself heard.

The book’s text is pitch perfect. It alternates statements and questions: “When you listen to music, your heart changes rhythm. Can you hear it? Some of the statements may seem self-evident: “If you are sad, it can make you feel better.” Still, they need to be said. The feelings evoked by listening to, or making, music, are largely involuntary: “You don’t decide all this. It just happens.” Some statements are broader, with social and political implications: “Music is a bridge that unites us.”

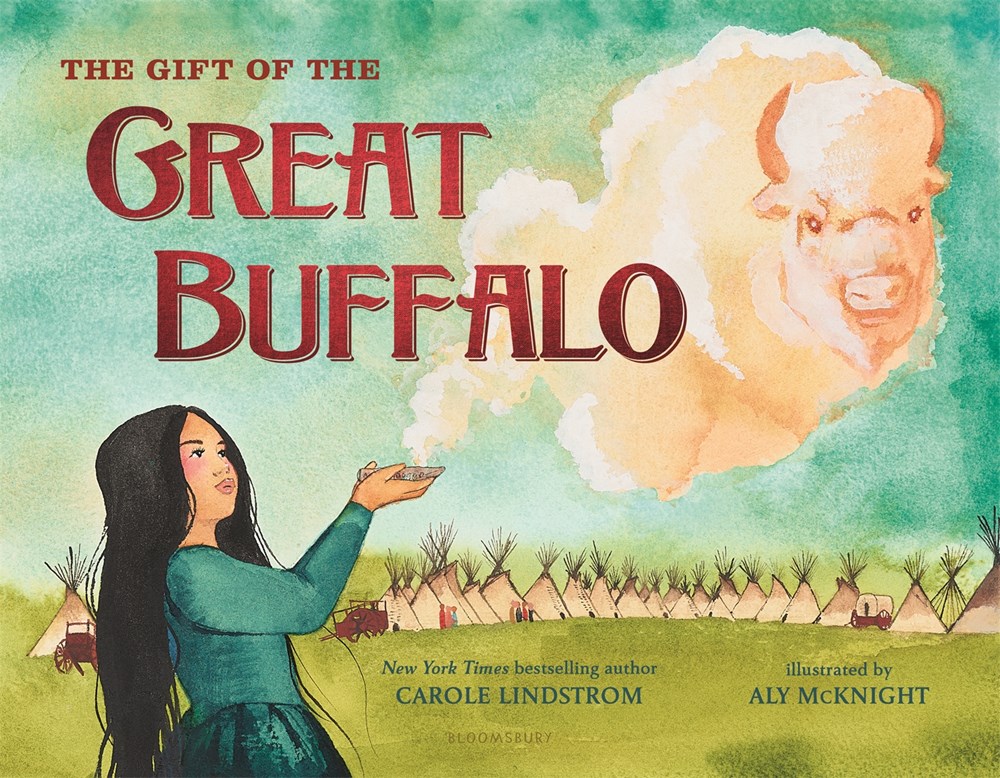

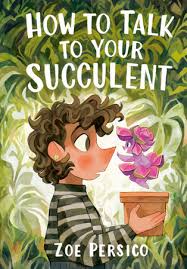

A book composed of generalities about music would be less useful than this one. Readers of. Pantaleo’s work will learn about several distinctive forms of music, which are briefly explained a section at the end of the book. There are bagpipes, acoustic guitars, drums, harmonicas, and brass band. Musicians are from India, Bali, New Orleans, the American South, and Hawaii, and, of course, from your own community. The illustrations are boldly colored, and influenced by traditional art. (The also remind me of Maira Kalman’s work.) They also portray activity, but caught in a specific moment, as in a snapshot. A girl moves her hands across a piano keyboard, her eyes closed in concentration. A gospel choir captures “hope,” with their voices and hands. A girl sings in the bathtub with a brush as her microphone. Each image is its own performance.

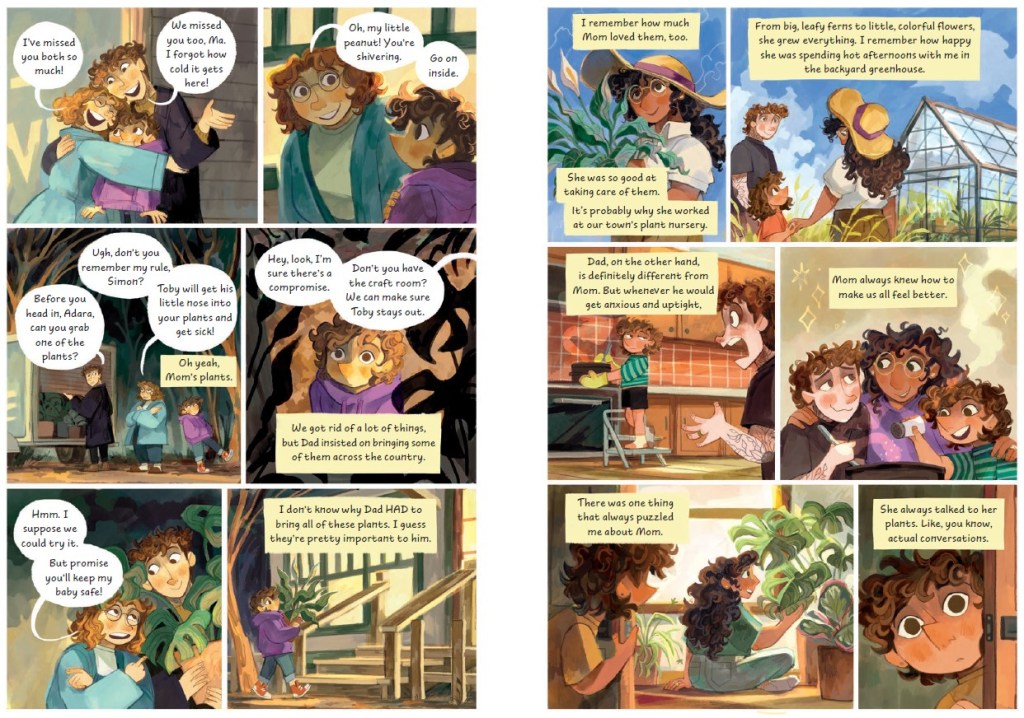

The design of the book and the composition of each page are also key notes to its success. Four young people surround a campfire. Each one has equal weight in contributing to the whole. A boy strums the guitar. A girl plays a flute. Two others do not play instruments, but they look up towards the sky at shooting stars and the moon. “Music is connection,” yet, at the same, time each individual in the scene experiences it differently.

The melody of words, the harmony of voices, the choreography of figures, all make And There Was Music instrumental in helping children to understand this form of language. After you share it with them you will both continue to hear the echoes.

Music is connection.